In Memoriam 2023

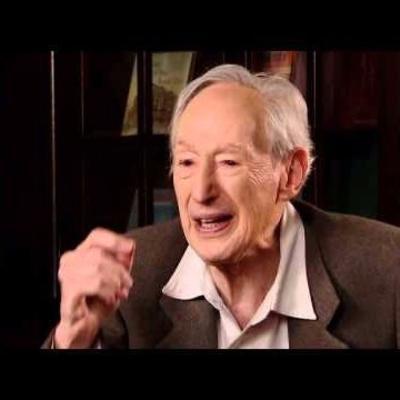

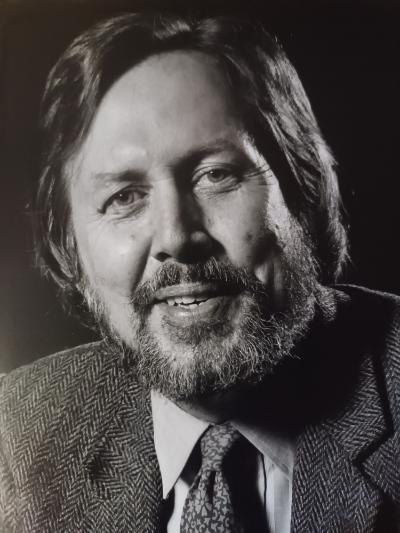

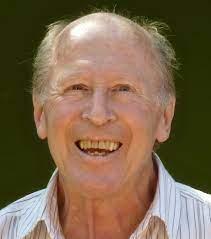

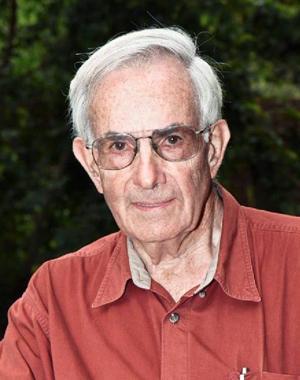

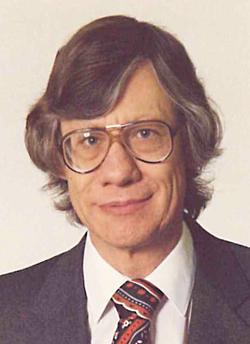

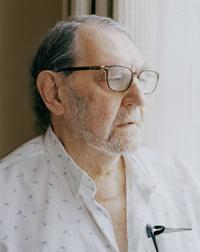

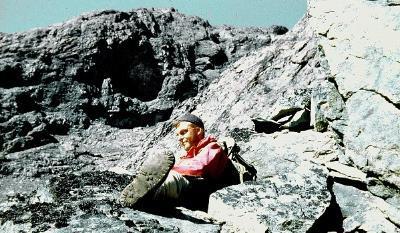

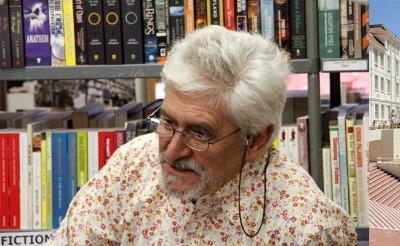

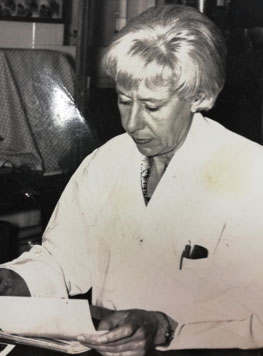

Alfred William Stadler (1937-2023)

Former professor and chair of the Department of Political Studies at Wits, Alfred William Stadler, "Alf" (BA 1960, BA Hons 1962, PhD 1971), died on 29 December 2023 at the age of 86. Alf was a public intellectual, providing analysis and commentary on election results and political events; he acted as an expert witness for the defence of his students who were charged with “terrorism” by the apartheid regime; and, for a time, he chaired the Institute for the Advancement of Journalism.

Alf was born in Durban in 1937, the son of a former dairy farmer, who worked for the South African railways and who died when Alf was 10. The family relocated to Johannesburg; Alf recalled the train ride to the Reef as deeply depressing: the cold, dry and treeless khaki veld of the Rand were a stark contrast to the sub-tropical forests and rolling cane fields of Natal. In Johannesburg, Stadler’s mother washed and ironed clothes in exchange for backyard accommodation.

As a student at Highlands North Boys High, Alf's academic performance was mediocre. His principal suggested that he take up a less intellectually demanding trade of some kind. But he had long nurtured a keen interest in English literature. As a youngster he checked out books such as James Joyce’s Ulysses from the local library, much to the librarian’s chagrin. When he left school he studied metallurgy, but he dropped out after a short stint at a steel foundry where dodging projectile lumps of iron ore were not infrequent hazards. He then enrolled in a BA and studied English and Politics. Politically conscientised, he joined the Communist Party, joking wryly about his failed attempts to mobilise residents of Alexandra Township and avoid arrest.

At the time, the Political Studies Department was managed by Godfrey “Copper” LeMay, and Alf was one of a few PhD students. LeMay held supervisory sessions at the Wits cricket nets to practice Alf’s batting, and hosted “seminars” at the Devonshire Hotel bar in Braamfontein. Following LeMay’s retirement in 1966, Alf was appointed acting head of the department but was only granted full professorship and the chair in 1981. By the early 1980s, he had transformed the department.

During his tenure, Alf purposefully appointed young intellectuals with wide ranging interests and potential. Committed to mentoring early career academics, he granted junior staff time off from lecturing so they could pursue their research and publish. When he joined the department in the early 1980s, Prof Tom Lodge described the atmosphere as a “considerate and hospitable setting for an apprentice lecturer”.

In his inaugural lecture at Wits, Alf stated: “I want to raise questions about how people without power, wealth or even votes act politically, and try to estimate the effects they produce on political structures”. His research and writing focused on historical uprisings and mini revolts in South Africa, such as the bus boycotts and squatter movements on the Reef. “Birds in the cornfield: Squatter Movements in Johannesburg, 1944-1947" is still listed as essential reading on the Abahlali baseMjondolo, the socialist shack dwellers movement of South Africa’s, website. His book, the Political Economy of Modern South Africa (Routledge 1987 and 2022) was favourably reviewed and is still frequently cited. Much to Alf's delight the book was recently republished. The reconfiguration of what defined political studies at Wits led to the introduction of new curricula, notably an honours level course taught by Alf and Prof Lodge called “Direct Action and Popular Protest” that explored the political agency of people who lacked resources.

In recognition of his talent for leadership, Alf was also appointed caretaker head of the Department of Music; he proudly showed off his new office that was outfitted with a baby grand piano and a music system.

At home, his family remember that he was constantly busy: an accomplished carpenter he built bookshelves, constructed dry walling, and fitted out the family kitchen all from scratch; he was a great cook — no meal was complete without recitations from Robert Carrier, Elizabeth David and Larousse Gastronomique, inspiring future feasts; he loved opera, was an avid reader, and refused to own a television set.

He leaves his wife, Jenny, his daughters Josie and Cathy, his son Jonathan (BA 1989, BA Hons 1990, MA 1995), his sister Francis, and his seven grandchildren.

Source: Jonathan Stadler

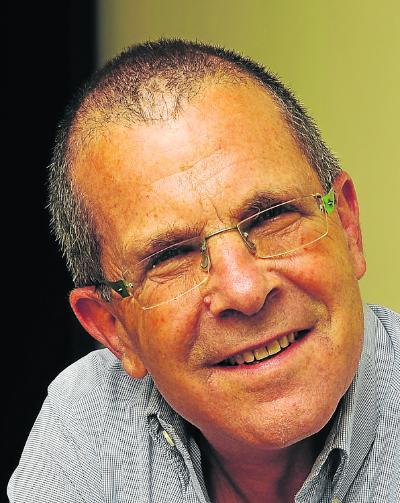

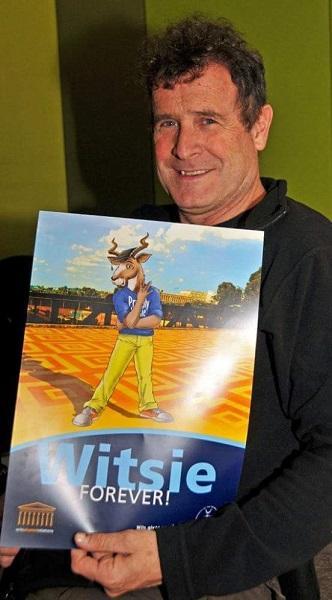

Mark Finkelstein (1966-2023)

Mark Finkelstein (BCom 1987, LLB 1989) a lawyer, admired for his teaching of martial arts and voluntary efforts, died of cancer on 27 December 2023 in Johannesburg. His death came a few weeks before what would have been his 58th birthday. He was first diagnosed with cancer four years ago, and despite pain, continued to work and maintained his good humour.

Finkelstein was born and grew up in Johannesburg. He matriculated at Highlands North Boys High School, and then went on to study at Wits. As estate agents, his parents often found new homes and moved with Finkelstein, his older brother Oscar and sisters, Lani and Aviva.

Finkelstein said he was a lawyer by profession, but his passion was teaching Krav Maga, Hebrew for close combat, an Israeli developed self-defence system. For more than 20 years he volunteered for the Community Security Organisation, which protects Jewish institutions and events.

One of the greatest influences on Finkelstein’s life was the late Mickey Davidow, a Judo sensei. Finkelstein represented Transvaal and won several national titles in Judo. In a tribute to Davidow, who passed away two years ago, Finkelstein wrote that in his own martial arts instruction, he followed his sensei’s “kind and calm encouragement of students, while being specific in any criticism.”

His teaching went beyond martial arts and he lectured on how “The Art of War” written by Sun Tzu, the ancient Chinese general, could be used as a tool for fighting addiction, in thinking about business, and daily life. He had begun to write a book on “The Art of War” and fighting addiction. Finkelstein also spoke to groups about his fight against cancer.

Finkelstein had a hectic schedule, but found time to give of himself. He regularly visited the elderly parents of friends who had emigrated. He paid attention to his children in teaching them, exercising with them, and taking up their interests. He frequently took the family for hikes in nature reserves, and on holiday at his favourite places in Mozambique.

He leaves his wife Cheryl and five children.

Sources: Finkelstein family and SA Jewish Report

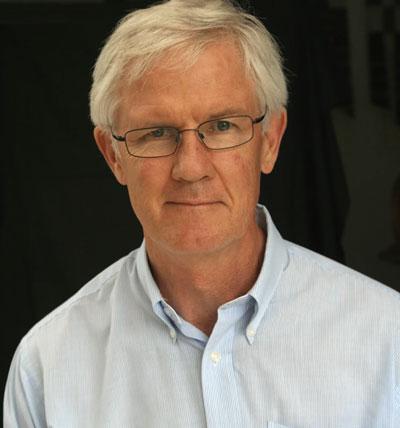

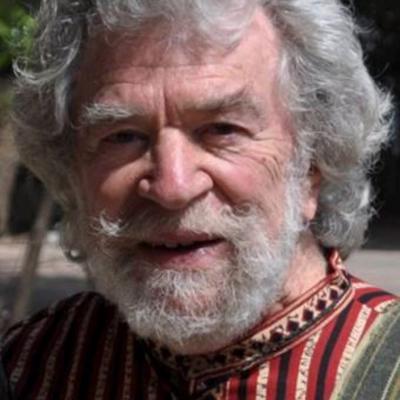

Conrad Mueller (1949-2023)

Professor Conrad Steven Mueller (BSc 1975, BSc Hons 1976, PhD 1989) a pioneer of computer science at Wits and in South Africa died on 23 November 2023. He was born in Johannesburg in 1949 and matriculated at King Edward VII High School.

After completing his honours degree, he spent a short time in industry, and completing his master’s degree at Rand Afrikaans University (now the University of Johannesburg), he returned to Wits in 1981 in response to a call to help a new division as it was emerging into an independent Department of Computer Science. He spent the next 33 years at Wits, rising through the ranks to associate professor. He served as Chair of the Governing Committee and then Head of School for about 10 years.

Prof Mueller quickly proved himself to be an extremely dedicated teacher in a tough environment. Wits, as an established research university, considered Computer Science to be an upstart new discipline, particularly as few members of staff had PhDs in the early days.

Prof Mueller’s great strength was the time and interest that he put into the people around him. As a teacher he is fondly remembered for the one-on-one work that he did with students. In the 1980s and 1990s it was common to find a queue of students outside his office getting help. He would spend hours with students helping them debug terrible code, and more importantly teaching them and fostering independent thinking.

Prof Mueller mentored young members of staff, advising them on teaching strategies and how to deal with various teaching and administrative problems. He could always be relied on to read drafts of research papers critically and constructively and was happy to listen to research problems and talk through possible solutions even for projects outside of his area of expertise. He was always prepared to take on administrative tasks, large and small, and sheltered the younger members of staff from that work. This nurturing mentorship launched several academics into their own successful careers.

He had to be tough to protect and help build computer science as a discipline. Yet in the end, the new department met with some great successes, particularly students who went on to become industry leaders.

He was an old-fashioned scholar – he read widely and deeply and had an open sense of enquiry. He taught a wide range of computer science courses from first year to honours. He made important contributions to computer science education research. His research passion was computer architecture – he recognised early the limitations of the von Neumann architecture and proposed alternative models and programming styles. He completed his PhD in the late 1980s under Judith Bishop – Towards removing sequential ordering in programs and continued work on this theme for the rest of his life.

As a son of German and Swiss immigrants who had seen the rise of fascism in Europe, Prof Mueller was brought up to oppose apartheid. He was a member of Mervyn Shear’s “Peacekeepers”, a group of academics who in the 1980s would put themselves between the police and students to restrain police violence, and active in the anti-apartheid Union of Democratic University Staff Associations.

After he reached mandatory retirement age, he taught at Tshwane University of Technology and continued to supervise postgraduate students at the University of South Africa. He was also elected to the Wits Executive Committee of Convocation and was one of the Convocation members of the University Council. He gave great service to the University and could be relied upon to take on unglamorous jobs. He showed commitment and personal courage during the Fees Must Fall protests.

Prof Mueller was a great personality and someone who was a good friend as well as a colleague. He was also a pioneer of good coffee. The departmental wine club, Turing Tipplers, held his sense of taste and smell in high regard. He often entertained colleagues at home and would show immense kindness to new members of staff, putting them up and even schlepping them around town. In cases of personal crises, he was always willing to help. His unusual turns of phrase – Conradisms as his staff irreverently called them – can’t be repeated (though they never fell on flat ears). You had to be there to appreciate them.

His sense of what was right meant that he sometimes would not compromise. He could not resist the temptation to argue or disagree with positions that he thought were wrong. As a result, he could drive his colleagues to distraction and was the bane of generations of Deans and Vice-Chancellors. But his sincerity and passion left Wits a better place.

He is survived by his partner Judy Backhouse (PhD 2009) and sisters Ann-Christine Andersen (BA 1967) and Dr Jane Mueller (MBBCh 1969).

Sources: Adapted from The South African Computer Journal by former colleagues Scott Hazelhurst (BSc 1985, BSc Hons 1986, MSc 1988) Bob Baber, Yinong Chen, Philip Machanick (BSc Hons 1981, MSc 1988) and Sarah Rauchas

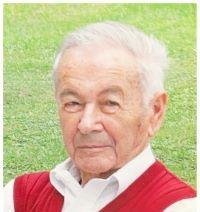

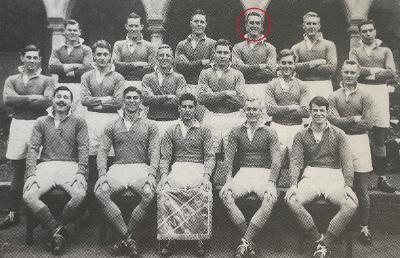

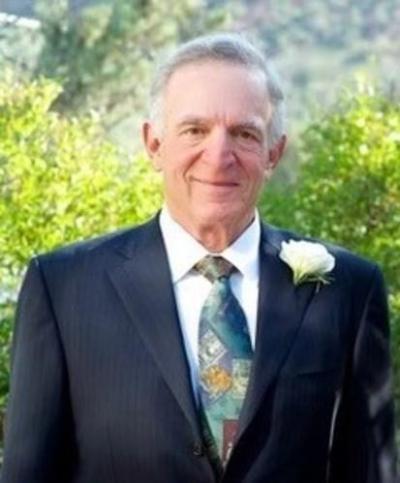

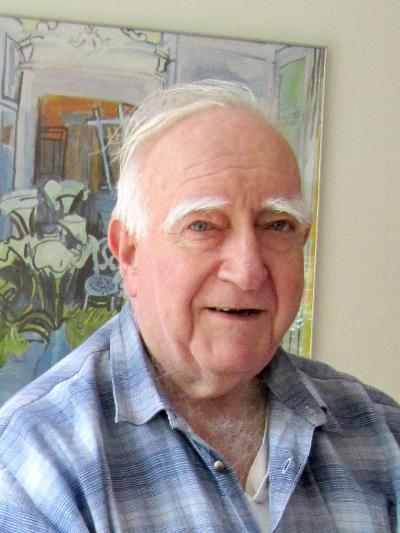

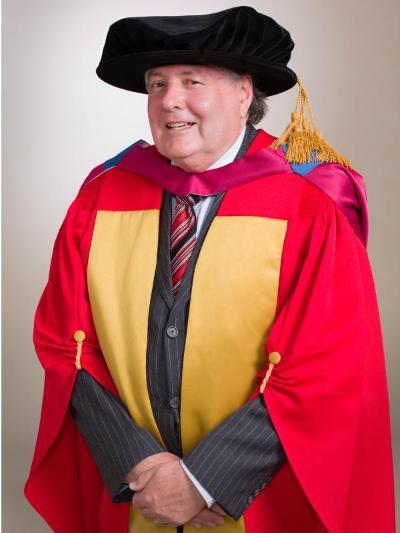

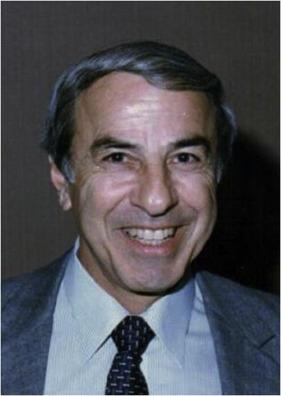

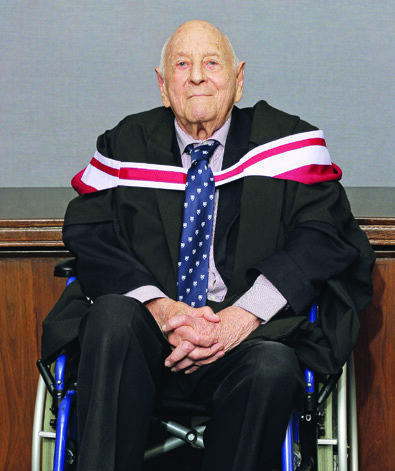

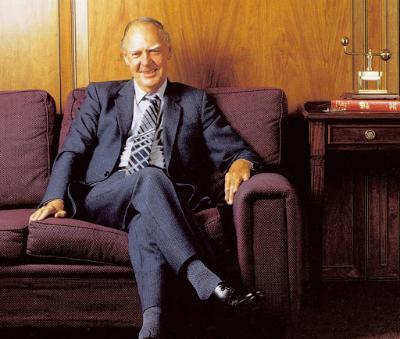

John Steele Chalsty (1933-2023)

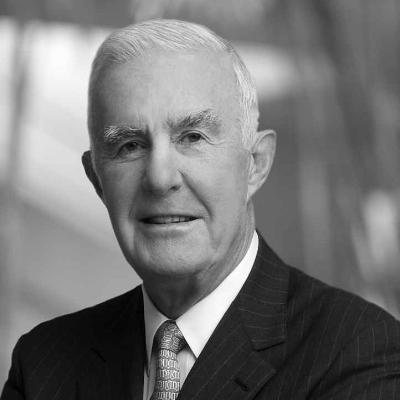

John Steele Chalsty (BSc 1953, BSc Hons 1954, MSc 1955, DCom honoris causa 2005) business leader, former chairman and chief executive officer of Donaldson Lufkin & Jenrette Inc and founder of the Wits Fund in the US, passed away peacefully at the age of 90 in his home on 12 November 2023.

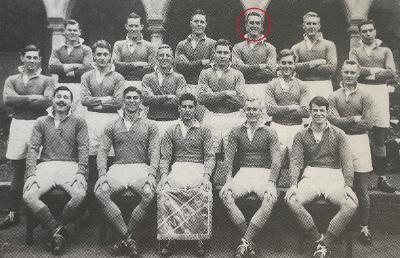

Chalsty was born in 1933 and began his academic journey at Wits, completing honours and master’s degree in chemistry and physics. He is remembered for his sporting prowess as a member of the Wits Rugby First XV. In 1954 the team beat Pretoria University 12-0. After receiving the Stanvac Scholarship in 1955, he travelled to the US to study at Harvard University.

In a 2007 interview he said: “I had turned in work at Wits on a PhD in chemistry and thought I could pick it up at Harvard," he recalls. It wasn't so easy, however. "I heard I would have to start all over again. Another four years of chemistry was appalling. I looked around for something to do and discovered the business school. I found I had somehow stumbled into the right career."

In 1957, he earned his MBA from Harvard Business School, graduating with high distinction as a Baker Scholar. He worked at Standard Oil of New Jersey (now Exxon) for around 12 years in various roles in the US and Europe. In 1969 he joined Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette (DLJ) as an oil analyst, rising through the ranks to become president and chief executive in 1986 and chairman in 1996. Under his leadership, DLJ transformed into one of America's most successful investment banks. He was widely known for a collegial style that earned the respect and admiration of his employees and peers.

Chalsty also served in leadership roles with other prominent institutions, including vice chairman of the New York Stock Exchange, president of the New York Society of Security Analysts, and board member of Occidental Petroleum, Metromedia International Group, Inc, and Sappi Global.

In 1992, he met Nelson Mandela, two years after his release from prison. “He had come to the United States trying to enlist people to go to South Africa and watch the polls,” Chalsty said. Mandela was worried about fraud and wanted to ensure the election was administered fairly. “I met him at a luncheon in New York City.” The encounter was brief and mostly at a distance, but it revealed Mandela’s practical side, Chalsty said. “The remarkable thing about this man was that he was undoubtedly one of the most saintly figures I’ve ever seen, but at the same time he was an extremely able politician.”

In 1995 he was chairman of the New York Host Committee for the 50th anniversary of the United Nations.

A dedicated philanthropist, Chalsty held prominent positions in organisations such as Lincoln Center Theater, American Ballet Theater, New York Philharmonic, Overcoming Obstacles, Teagle Foundation, New York City's Economic Development Corporation, Harvard Business School, Columbia University, and Saint Barnabas Medical Center.

When he stepped down as CEO of DLJ his colleagues commemorated his nearly thirty years of distinguished service to the firm by establishing the John S and Jennifer A Chalsty Fellowship at the Harvard Business School. The fellowship is used to support black South African MBA students.

He did not forget his beginnings and remained a supporter of South Africa. He helped to establish the University of the Witwatersrand Inc. (the Wits Fund) in the United States, an entity that continues to be of vital importance to the University. The Chalsty name is proudly emblazoned on one of the outstanding meeting spaces on West Campus, associated with the Mandela Institute and the School of Law, because of his pivotal and founding donation to the Institute.

Chalsty’s many achievements and generosity were widely recognised, including with honorary doctorates from Wits in 2005 and the Medical University of South Carolina in 2015. He received the Ellis Island Foundation's Medal of Honor. He was also honoured by the Citizens Committee for New York City and by the President's Medal for Excellence awarded by Boston College to individuals who have distinguished themselves through personal of professional achievements which exemplify the ideal proclaimed in the University's motto, “Ever to Excel”.

He had “an imposing physical presence”, was described as “incredibly generous, humble and unpretentious,” with a “dry wit”.

He is survived by his wife Jill Siegal Chalsty; his daughters Susan Neely and her husband John Neely, and Deborah Chalsty; his grandchildren John Harrison Neely and his wife Jacqueline Neely, Meghan Bowman and her husband Stephen Bowman, and Timothy Neely; and his great-grandchildren Henry and Penelope.

Sources: Wits archives, The Post and Courier and Dignity Memorial

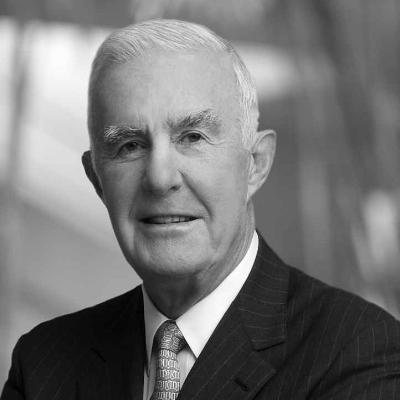

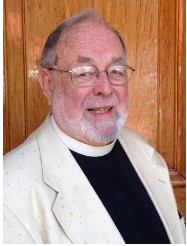

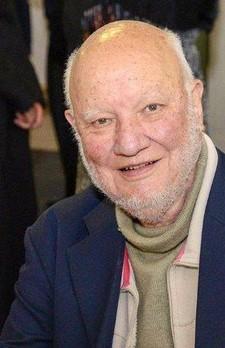

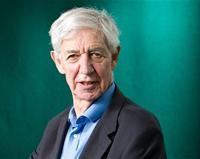

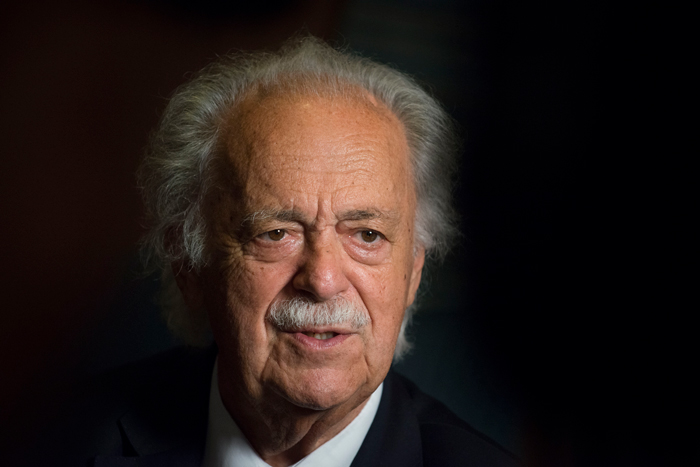

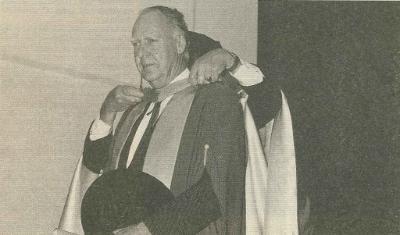

Thomas Lodge (1951-2023)

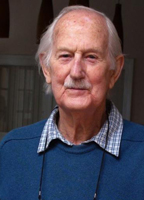

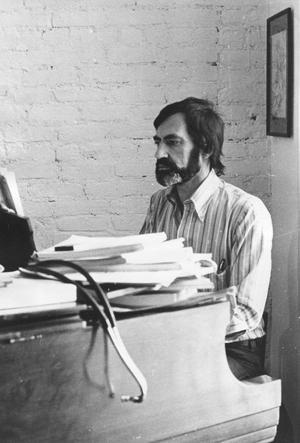

Respected former Wits academic and lecturer, Professor Tom Lodge, died at the age of 72 on 8 November 2023. He was a dominant figure in charting South Africa’s modern political history, in particular the history of its anti-apartheid liberation movements. At the time of his death he was Professor Emeritus in Peace and Conflict Studies at University of Limerick in Ireland.

Born in Manchester, Professor Lodge was the son of Roy and Vera Lodge (née Kotasova). He was schooled in Nigeria, North Borneo (later part of Malaysia) and England, travels dictated by his father’s British Council work, which, according to his brother, Robin, provided an early impetus for his later interest in developing countries heading towards independence. He joined University of York as an undergraduate student in 1971, obtaining his PhD at York in 1985.

He first came to South Africa in 1976 as a research fellow of York’s newly opened Centre for Southern African Studies, visiting Soweto in the company of a local Anglican priest. He returned home two days later, he would recall, “to read that Soweto was in flames”. Two years later he was employed as an assistant lecturer in the Wits Politics Department.

Professor Lodge closely studied South Africa’s anti-apartheid movements in opposition and then, after 1994, in power. He also followed political developments in post-apartheid South Africa, analysing, among many other things, corruption and election results. His work on the ANC, PAC and other liberation movements, based on rich fieldwork, established him as a key political and social historian. He was a member of the Wits Politics Department for 25 years and published key texts on South African black opposition politics, South African post-apartheid politics, the figure of Nelson Mandela and, most recently, the South African Communist Party.

In 2005, he left South Africa and took up the position of professor of peace and conflict studies at the University of Limerick, before becoming dean of arts there in 2012. He retired to Saint Seurin de Prats, near Bordeaux in France, in 2021, but continued to travel to South Africa, where he served on several trusts and commissions. At the time of his death, he was close to finishing a work on Walter Sisulu.

In a tribute, colleague Professor Daryl Glaser, described Prof Lodge as “kind, humble, understated and good humoured.” His lecturing style was “unusual” with “little eye contact but lots of fascinating detail delivered in a mellifluous voice.” In the 1980s students flocked to his lectures and he rarely locked his office door. In response to the suggestion that students might help themselves to his impressive book collection, he replied ‘I wish’.

He is survived by his wife Carla and their two sons, Kim (BAS 2002, BArch 2005) and Guy (BA 2004, BA 2005).

Sources: The Guardian, Prof Daryl Glaser (BA 1982, BA Hons 1983, MA 1989), Wits archives

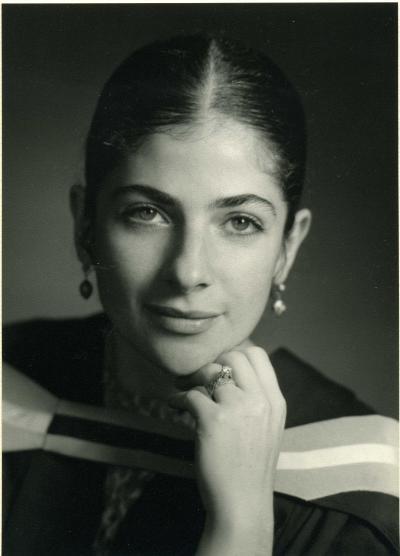

Gladwyn Leiman (1944-2023)

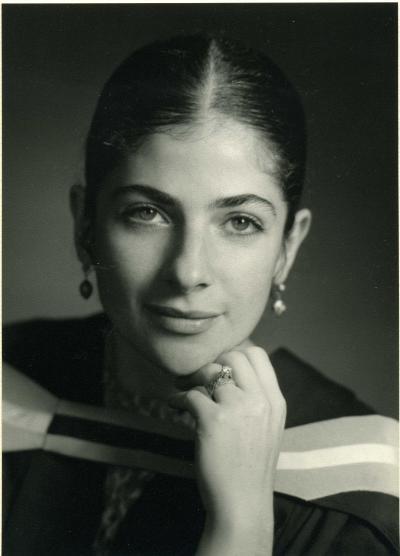

Former director of cytopathology at the University of Vermont College of Medicine in Burlington, Professor Gladwyn Leiman (MBBCh 1967) passed away in Vermont, United States, on 1 October 2023.

Professor Leiman’s distinguished career began at Wits and after her surgical and medical internships at the Johannesburg General and Baragwanath hospitals, she was appointed medical officer and subsequently an associate professor in the Cytology Unit of the Department of Anatomical Pathology in the School of Pathology of the South African Institute for Medical Research in 1971. Professor Leiman gained international acclaim for, inter alia, her “Project Screen Soweto” programme, which led to a significant reduction in cervical cancers by monitoring cancer precursors and establishing family planning protocols in Soweto.

In 1999, the refurbished laboratory at the South African Institute for Medical Research was renamed the Gladwyn Leiman Cytopathology Centre. She was a sought-after speaker among the international obstetrics and pathology communities, travelling and lecturing extensively in the US, Canada, Australia, England, India and the Middle East. She was recruited as the director of cytopathology and as a professor of pathology at the University of Vermont Medical Center in Burlington. Here, her fine needle aspiration skills brought her recognition as an excellent diagnostician, teacher and clinical researcher.

At the International Congress of Cytology in Paris, Professor Leiman received the 2012 Maurice Goldblatt Award: “For her lifelong love and dedication to clinical cytology; for her very special relationship to underserved areas of the world and her willingness to bring knowledge and expertise to people deserving improved medical care; for her academic rigour and achievements in publishing and teaching.” She was awarded honorary membership of the Indian Academy of Cytologists and the South African Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. In 1996 she was named as a Light Source Personality of Cytopathology by the International Academy of Cytology.

On retirement she said: “My future plans are to resurrect my right brain, and re-enter the worlds of literature, music and history, which were my major interests before I deviated to medical school. In particular, I want to reengage in Holocaust studies and genealogy, which have been constant unofficial pursuits throughout my life.”

Professor Leiman’s family said she “rarely spoke about her accomplishments” and “was at once highly gregarious and intensely private”. Fellow alumni described her as an exceptionally kind, caring and compassionate person and a loyal friend. She “provided the glue” that held her Wits Medical Class of 1967 together for more than 50 years.

She is survived by her two brothers Russell and Darryll and their families.

Sources: Cancer Cytopathology and Dr Helen Feiner, née Katzew (MBBCh 1967)

Claude Hakim (1942-2023)

Dr Claude Hakim (MBBCh 1956) was a distinguished member of a remarkable class. After his internships he spent seven years in London with appointments at Charing Cross and Hammersmith hospitals.

Dr Hakim emigrated to Australia, arriving in Sydney in 1979, where he went into private practice in obstetrics and gynaecology. He was French speaking and fluent in five other languages, which he used daily in his practice.

He enjoyed travelling with his wife Roslyn and they visited France almost yearly. He was a gourmet and enjoyed fine wines, which he collected. He was truly a “bon vivant”.

He attended Athlone Boy’s High, where he was an outstanding rugby player and eventually school captain. An abiding vision, when Roosevelt High played Athlone, was Hakim running 25 yards to score under the posts, with four of the opposing team hanging onto him.

Dr Hakim was a skilled surgeon and his patients “thought the world of him”. He will be remembered as a loyal friend, who “was a kind and thoughtful person”.

He is survived by his wife Ros and sons Jean-Marc and Daniel.

Source: Dr Roger Pillemer (MBBCh 1965)

Werner Kirchhoff (1931-2023)

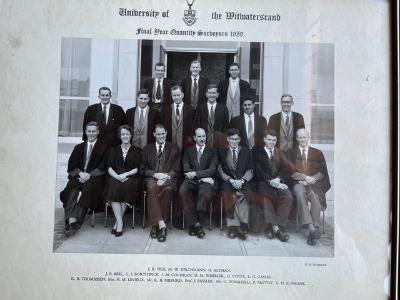

A land surveyor of distinction and a pioneer of South African satellite geodesy, Werner Kirchhoff (BSc Eng 1957) died at the age of 92 in August 2023.

Werner, born in Germany in 1931, was the son of Peter Kirchhoff and Margarete Bose. Two years later his family left Germany for South Africa, settling in Johannesburg in 1934. During Werner’s time at Pretoria Boys’ High School, he became fascinated with the way the land surveyors at the school measured angle and distance. This led him to study surveying at Wits.

Werner was influenced by his father in developing a special interest in astronomy. His early post-graduate surveys established whole degree lines of longitude and latitude in the Zambian (then the Northern Rhodesian) bush from basic astronomical field observations by precision navigation from stars. The USA’s Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory originated the project and Werner became associated with this institution in 1958 as an honorary observer for the International Geophysical Year.

In 1959 he was asked to join the observatory staff and to be involved with satellite tracking and later managing the Smithsonian Institution’s precision satellite photographic observation station at Olifantsfontein. He was awarded a medal for his observations.

He married Anna-Maria in 1961 and the couple had four children: Peter, Elizabeth, Teresa and Christopher (BSc Eng 1987).

Returning to South Africa in 1970, Werner established his own land surveying practice. He saw the application and benefits in the construction industry of laser instruments to achieve greater speed and accuracy in surveying.

When the family returned from the US he served for several years as chairman of the Parktown Association. In 1997, following his retirement, he took up new interests in heritage and collecting Africana. In 2014 Werner re-discovered the beacon (dating from 1919) on Oxford Road, about 100 metres south of Glenhove Road.

His last few months were spent at an old age home where he peacefully passed away in his sleep.

Sources: Kathy Munro (BA 1967), The Heritage Portal

Doreen Mantle (1926-2023)

Doreen Mantle (BA 1948) died aged 97 in her London home on 9 August 2023. She was best known for her role as Jean Warboys, the annoying friend of Victor Meldrew’s wife, Margaret, in the BBC series “One Foot in the Grave” (1990-2000).

She was born in Johannesburg on 22 June 1926 to English parents, Hilda (née Greenberg) and Bernard Mantle, who ran a hotel. The family moved to England, returning to South Africa in 1930, shortly after the birth of her brother, Alan (BSc Eng 1953).

Mantle was schooled at Barnato Park for Girls and obtained a BA Social Science degree at Wits in 1948. Her stage career started while performing with the University Players, the Johannesburg Repertory Society, the Munro-Inglis Company and the National Theatre. She was also active in radio in the early 1950s in shows devised by Ian Messiter, who later in the UK, would create BBC Radio 4’s “Just A Minute”.

Shortly after graduating, Mantle worked as a social worker in the townships around Johannesburg, witnessing first-hand the social injustice of apartheid. She followed this with work for Legal Aid South Africa. Here she was able to provide support for activists during the growing resistance to the government. In later years she would reflect on these experiences in her one-woman show “My Truth and Reconciliation”.

Mantle met Joshua Graham-Smith, a computer engineer, at the theatre and they married in 1952. Aware that she was being investigated by the authorities for her activism and not wanting to bring up children under apartheid, the couple emigrated to the United Kingdom. “I wanted to see new places, to get away from parochial views and to change the world,” Mantle said.

In the United Kingdom she established herself as a prominent actress in stage, television and film. She carved a niche in the hearts of the British as the catalyst for surreal plot twists. The series writer of “One Foot in the Grave”, David Renwick, recalled: “No one else could have played Mrs Warboys as she did and the honesty that she brought to every line, however bizarre, was what made the character so funny and legitimised even the maddest of moments. There was never the remotest suggestion that she was playing comedy: in her hands it was all utterly real.”

Her fame led to appearances in shows such as a “Weakest Link” sitcom special in 2002. Asked by the host, Anne Robinson, for her most memorable moment, she replied, deadpan, as in the mode of her character: “I was rolled down a hill and mounted by a dog.” The studio audience roared with laughter.

She toured Britain and performed at the National Theatre in The Voysey Inheritance. In 1979 she was awarded the Laurence Olivier Award for Best Actress in a supporting role for her performance in “Death of a Salesman”.

A highly intelligent woman of strong opinions, she worked closely with Richard Attenborough at the Actors’ Charitable Trust and latterly campaigned for visually impaired elderly people, of which she was one.

She is survived by her sons Quentin and Nicholas and her brother Alan.

Sources: Wits archives, The Guardian, Alan Mantle

Jani Allan (1951-2023)

Isobel Janet Allan (BA FA 1975, PDipEd 1977) better known as Jani Allan, the former columnist, died at the age of 70 on 25 July 2023 at the Chandler Hall Health Services Hospice in Pennsylvania, United States. Voted the “Most Admired Person in South Africa” in 1987, she was a glamorous trendsetter, concert pianist, model, teacher and waitress. Her career nosedived after a 1991 British documentary The Leader, His Driver and the Driver's Wife by Nick Broomfield alleged she had been sexually involved with right-wing leader of the Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging Eugene Terre’Blanche.

Allan was born in 1951 and adopted as a one-month-old by John Murray Allan and his wife Janet Sophia Allan (née Henning). John was Scottish and came to South Africa for the climate. He was chief sub-editor at The Star newspaper in Johannesburg. He died eight months after the adoption.

In her memoir Jani Confidential (Jacana, 2015) Jani described her childhood as “a parade of gymkhanas and piano recitals”. She wrote: “My mother was an antique dealer. She had horreur de vacui – horror of empty spaces. Persian carpets were layered upon each other at our Bryanston home.”

At the age of 10, she made her debut with the Johannesburg Symphony Orchestra. A year later, she won the Trinity Cup of South Africa, tying with Greta Beigel, a 21-year-old pianist. Professor Jacob Epstein and Professor Adolph Hallis, celebrated concert pianists, were among her mentors.

She initially applied to do a music degree, but enrolled for a degree in fine arts instead at Wits. She said she yearned “to be a hippie and wear tie-dyed clothing and hand-tooled leather sandals”. She prolonged her time at Wits by enrolling for a post-graduate high school teaching diploma. She told WITSReview her favourite lecturer was Robert Hodgins: “Robert used to tell us that painting was ‘a bit like surfing’ in that a good deal of the time is spent bobbing about, waiting for the right wave to come along. He explained that there are paintings that stem from memory and from a sombre look at the human condition. There are paintings about the construction and confusion of contemporary urban life, but there are also paintings about the pleasures about being alive, pleasures that crowd in upon the pessimism everywhere and refused to be ignored … A painting of my life at Wits would be such a painting.”

She met her first husband, Gordon Schachat (1982-1984), on campus. Apparently when he saw her walking down the steps at the Great Hall, he decided then and there to marry her. The marriage lasted two years. She also married Dr Peter Kulish (2002-2005). Her partners included Stanley B Katz (BCom 1972) and Mario Oriani-Ambrosini.

Her first job was teaching history of art at Greenoaks School. Later she taught art and English at Bryanston High School. She started writing classical music reviews for The Citizen newspaper and moved to the Sunday Times. The editor, Tertius Myburgh, hired her on the strength of her music reviews. Within a week, Leslie Sellers designed the logo for her debut column, “Just Jani”. He dropped T from Janet as it would not fit. Her first column appeared in March 1980. Weeks later, she was in Corfu to interview Roger Moore on the set of the latest James Bond series, For Your Eyes Only. In her decade-long tenure at the newspaper, she became the country’s most famous and influential writer and columnist. Her column later became “Jani Allan’s Week”, detailing her busy social diary. In later years it morphed into a straight interview profile column, “Face to Face”.

Of her hometown, Johannesburg, she wrote: “Johannesburg has never been a place for the fastidious or the over-sensitive. It is hideous and detestable, luxury without order, sensual enjoyment without refinement, display without dignity”. And “In South Africa acquisitiveness is not so much a virus as a chronic disease of epidemic proportions. Money is what death was to Keats. A preoccupation.”

In a surreal twist of fate, Allan’s last job was as a waitress in a fine-dining restaurant in the small town of Lambertville, in New Jersey. She became a US citizen and lived in “a small ground-floor apartment, against a steel traffic barrier and a parking lot”, according to a 2013 article. She was simply known as “Juliette” – her mother’s childhood nickname – and shared her living space with her beloved Pomeranians, whom she described as “spirit guides in fur coats”.

She said in a SABC interview in 1995. “I think that my whole life, looking back at it, I was so rooted in worldly things, in worldly values, fame, fashion and fortune and all the things that are just transient.”

Sources: Wits archive, Mail & Guardian, News24 and Gareth Davies

David Charles Limerick (1939-2023)

Emeritus Professor David Limerick (BA 1960) died at the age of 84 on 13 July 2023 in Brisbane, Australia. He was born in Venterspost, where his father was mine manager, and matriculated at Krugersdorp High School. He completed a BA in psychology in 1960 at Wits and worked at the Institute of Personnel Research designing nonculture-specific IQ tests.

He married Brigid Murray (BA 1961, MEd 1972) and moved to Scotland in 1965 to undertake a PhD at Strathclyde on leadership, strategy, structure and culture. Thereafter he returned to Wits and, in 1975, aged 36, was appointed professor and head of Wits Business School.

In 1976, he was a visiting scholar at Harvard. In 1978, he emigrated to Australia, accepting a position at the University of Melbourne Business School. Within a year he was recruited by the innovative, new, multi-disciplinary Griffith University in Brisbane, as the foundation professor in organisational behaviour. He established the Graduate School of Management there and retired in 1996.

Professor Limerick’s research was published in key academic journals and culminated in his book, with a colleague: “Managing the New Organisation” (1993, 1998, 2002). His visionary views on organisational behaviour made him a highly sought-after management consultant, speaker and visiting professor at universities and organisations across the globe.

He was widely recognised as a forward thinker who offered groundbreaking insights on collaborative individualism, punctuated equilibrium, autopoetic models of change and interpretivist grounded models of self, leadership and change.

He is survived by his wife Brigid, daughter Tracey, son Michael, and six grandchildren.

Source: Professor Jennifer Kromberg (PhDMed 1986)

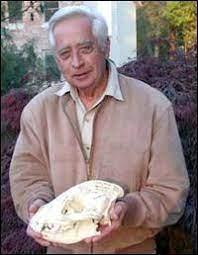

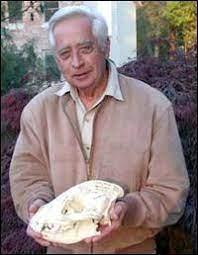

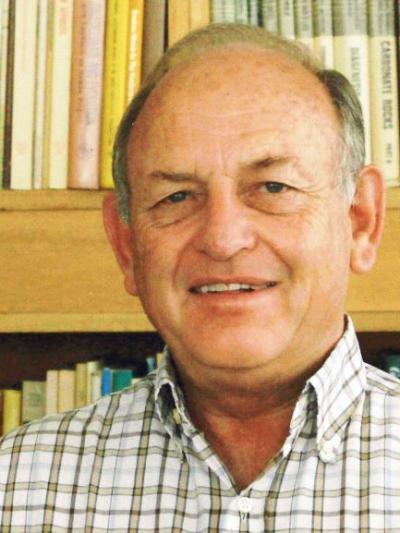

Charles Kimberlin Brain (1931-2023)

Dr Charles Kimberlin “Bob” Brain, pioneer in the field of palaeontology, died on 6 June 2023. He had dedicated his life to unravelling the mysteries of our shared human story and his most significant achievement was his work at the Swartkrans Cave in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site. Here, he made a series of discoveries that shed light on early hominin behaviour and evolutionary development, including the oldest evidence for the controlled use of fire by hominins, dating to about one million years ago. His influential book, The Hunters or the Hunted? An Introduction to African Cave Taphonomy (University of Chicago Press, 1981) revolutionised the field of palaeoanthropology. In it he developed the study of taphonomy: how organisms decay and fossilise.

Dr Brain was born on 7 May 1931 in Harare, Zimbabwe (then Salisbury) and he matriculated from Pretoria Boys’ High School in 1947. After obtained his Bachelor of Science degree and doctorate in zoology and geology from the University of Cape Town, he started his career at the Transvaal Museum (now the Ditsong National Museum of Natural History) in Pretoria, conducting research on rock layers of fossil hominid-bearing cave deposits. His systematic investigation revealed that each deposit had a distinct age and represented a unique climatic condition. Demonstrating his approach, Dr Brain assumed the role of curator in the Department of Lower Vertebrates in 1957, where he published several papers focusing on frogs, snakes and lizards. In 1968 he was promoted to director, a position he held for 23 years until his retirement in 1991. In 1980 he obtained his doctorate, titled “Studies in African cave taphonomy”, from Wits.

Wits awarded Dr Brain an honorary doctorate in 1981. He received other honorary degrees from the universities of Cape Town, Natal and Pretoria. His contributions to the field were also recognised with awards such as the Gold Medal of the Zoological Society, the Senior Captain Scott Memorial Medal of the South African Biological Society, the Achievement Award of the Claude Harris Leon Foundation and the John FW Herschel Medal of the Royal Society of South Africa.

He is survived by his wife Laura and four children Rosemary, Virginia, Tim and Conrad (PhD 1994).

Sources: Wits archive and Genus

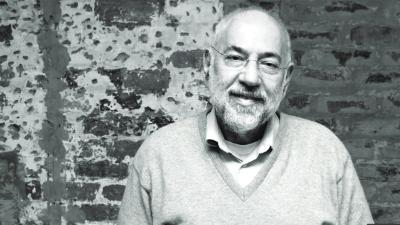

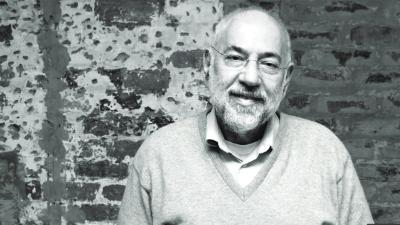

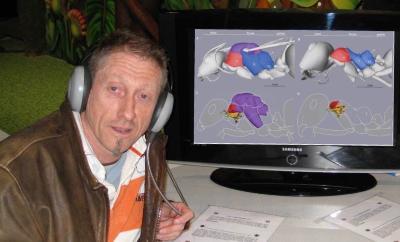

Barry Dwolatzky (1952-2023)

A much-loved Wits alumnus and “Grand Geek” of digital innovation, Emeritus Professor Barry Dwolatzky (BSc Eng 1975) died on 16 May 2023 after a short illness.

His relationship with Wits spanned more than 50 years and at the time of his death he was director of innovation strategy in the office of Deputy Vice-Chancellor: Research and Innovation – a position he described as his “dream job”. Even after retiring, he worked alongside Wits University’s deputy vice-chancellor, Professor Lynn Morris (BSc 1981, BSc Hons 1982), to establish the Wits Innovation Centre, which was launched on 17 April 2023.

Affectionately referred to as “Prof Barry”, he grew up in the northern suburbs of Johannesburg, living a relatively “insular childhood”. In 1971 he enrolled for an electrical engineering degree at Wits, going on to pursue a master’s degree, which he later converted to a doctorate. In his second year, he joined a student organisation, the South African Voluntary Service, which built schools and clinics in rural parts of southern Africa. The experience changed him profoundly, as he witnessed first-hand the reality of apartheid South Africa – villages filled with malnourished children, run by women and abandoned old men who’d had their lives sucked out in the mines. “I realised for the first time: how much my privilege and their underdevelopment were part of the same coin,” he said at the launch of his memoir Coded History: My Life of New Beginnings in 2022.

It was the beginning of a life as a political being, with a strong ethical compass. He left South Africa in 1979 to pursue research at the University of Manchester’s Institute of Science and Technology and at Imperial College in London. He worked as a senior research associate at the GEC-Marconi Centre in the UK, work which entailed software research and development projects. On his return to South Africa in 1989, his impact as senior lecturer was pronounced. He identified the importance of programming and information technology in engineering as well as introducing a software stream, which became distinct from the electrical engineering stream. He was made full professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering in 2000.

Prof Barry demonstrated skills as an innovator and strategist and was the major driving force behind the establishment of the Johannesburg Centre for Software Engineering in 2005. In 2013 he spearheaded the Tshimologong Digital Precinct. The centre attracted support from government and a range of local and international companies, including IBM. He was named “South African IT Personality of the Year” in 2013. He became Tshimologong’s first director and was honoured for this visionary project with the Vice-Chancellor’s Award for Academic Citizenship in 2016.

He received an award for Distinguished Service to IT from the Institute of IT Professionals of South Africa in 2016. In his acceptance speech Prof Barry said: “One of the things that I try to teach my students is that the hardest thing to manage is a software project, because you will be managing something invisible. This whole industry is invisible, yet it is the underpinning factor in the current fourth industrial revolution...” He loved young people and said: “Young people have the creativity and energy, the drive and the reason to build a new South Africa, a new Africa, and a new world. I believe in the future of our country. This is also the point of a university – to prepare people for the future.”

His life had many health challenges – he received a diagnosis of leukaemia in the 1987s and faced its recurrence in 2020. Yet, as a friend, Janet Love (BA 1988, PDM 1994), said, “he was able to do things – rather than dwell on a pile of lamentations”. He was generous with his time, listening attentively with kindness to everyone who crossed his path. Vice-Chancellor Zeblon Vilakazi used the Yiddish word “tzadik” to describe him: a wise, righteous leader respected for his sense of justice and wisdom and whose life’s work was shared among many.

He is survived by his wife, Rina King (BSc Eng 1981, PGCE 2008), and his children, Leslie (MA 2022) and Jodie (BA 2019, BA Hons 2020).

Sources: Wits archives, view memorial service

Winfried Franz Bischoff (1941-2023)

Sir Winfried Bischoff (BCom 1962) the former chairman of Lloyds Banking Group, Citigroup and JP Morgan Securities and CEO of Schroders, died after a short illness on 25 April 2023 at the age of 81.

Born in Aachen in Germany in 1941, he arrived in South Africa after his father had set up an import/export business in 1955. He graduated with a Bachelor of Commerce degree from Wits in 1962 and went on to attend New York University. Sir Winfried’s father nudged his son into a career in banking on the grounds that he’d “come across many bankers when building his business and none of them seemed to be very good,” Sir Winfried said.

He started his career at Chase Manhattan in New York. In 1966 he joined Schroders, which was a small investment bank and asset manager, and stayed for 34 years. At 29, he moved to Hong Kong to start the company’s Hong Kong operations. His first big deal was to help list Li Ka-shing’s property and manufacturing business. He returned to London in 1984 and was named Schroders’ chief executive at the age of 42. “Hong Kong was the making of my career,” he told the Financial Times in 2019. “Among candidates who’d remained in London during the 1970s, there was a sense of negativism. That’s why I think they skipped a generation and chose me.”

In the 1980s Schroders’ shares “were among the best-three performing investments” on the London Stock Exchange in the 1980s. Valued at £112m in 1984, Schroders was worth £4.5bn by 2000, when Bischoff took the call to sell its banking business to Citigroup.

He was awarded a knighthood in 2000 for his services to banking, and applauded across Wall Street, steering Citi through the early days of the US subprime mortgage crisis, acting as chief executive at the end of 2007 and serving as chair until 2009.

In 2009, he returned to the UK as chair of Lloyds Bank, which was reeling from its ill-advised takeover of HBOS and taxpayer bailout, which sparked public fury. He removed the chief executive and recruited António Horta-Osório in 2011, who shrank and de-risked the combined group.

Soon afterwards he became chair of auditing watchdog the Financial Reporting Council, but had to endure a series of accounting scandals amid corporate collapses. He also chaired JPMorgan Securities, the European arm of the US company, from 2014 until 2020.

“Much loved husband of the late Rosemary. Loving father to Christopher and Charles and devoted grandfather to five grandchildren,” his family shared in a statement after his death.

Sources: FT, Reuters and Moneyweek

Beryl Unterhalter (1928-2023)

Described as “one of those selfless souls who were the backbone of our country and Jewish community”, Dr Beryl Unterhalter (MA 1956) died on 4 April 2023 at the age of 95.

Dr Unterhalter excelled at school and majored in social work at Wits. She went on to train social workers, teach at a primary school, and lecture in social work at the University. She became a pioneering influence in the field of medical sociology.

During apartheid, she was an active member of the Liberal Party alongside her husband, Jack, who led the party in the Transvaal and worked as a civil-rights lawyer. The couple raised three children, Elaine (BA 1973), an academic in London, Karen (BA 1974), an educator based in Toronto, and David (LLB 1984), a Gauteng High Court judge.

She was “a woman of action”, with many projects on the go. She worked in early childhood education in Soweto; ran literacy programmes with young children and adults, collaborating on literacy and computer classes for domestic workers; and offered her skills to the volunteer organisation University of the Third Age (U3A). She told WITSReview in 2016: “When I retired from lecturing in sociology at Wits, I wanted to learn rather than teach. I wanted to pursue my interests in English literature, poetry and philosophy. I found my intellectual home in U3A. Among the group leaders were retired university staff who provide stimulating discussion in small groups with like-minded third-agers.”

After her death, her son David said: “People talk a great deal about the value of giving, but there are those who actually do it as opposed to thinking about it. My mother’s great virtue was that she was a doer of boundless energy and effort.”

Sources: Wits archive, SA Jewish Report

Shulamith Behr, née Ruch (1946-2023)

Honorary research fellow and former senior faculty member of the Courtauld Institute of Art at the University of London, Dr Shulamith Behr (BA FA 1969, BA Hons 1972) died on 7 April 2023 at the age of 76.

She was born in Johannesburg on 21 December 1946, into a family of Lithuanian Jewish heritage, and was the youngest of three sisters. She graduated from Wits in 1969, receiving the Henri Lidchi Prize as the top undergraduate student in history of art. She went on to lecture at Wits for seven years, when Professor Heather Martienssen was head of the department.

Dr Behr completed her studies in art history and theory at the University of Essex before joining The Courtauld’s faculty in 1990, as Bosch lecturer in German art. She held the post of senior lecturer in 20th century German art until her appointment in 2012 as honorary research fellow. As a specialist in the study of German Expressionism she admitted to having had a long “fascination with materials and print production in the works of the twentieth century”.

Her publications encompassed the contribution of women artists to German and Swedish modernism. Her richly illustrated “Women Artists in Expression: From Empire to Emancipation” (Princeton, 2022) explored how women negotiated the competitive world of modern art in Germany. Their stories challenge predominantly male-oriented narratives of Expressionism and shed light on the divergent artistic responses of women to the dramatic events of the early 20th century. Commentators have praised this work for “dismantling” the canonical histories of modernism as well as painting a clearer image of how women Expressionist artists were regarded during their lifetimes.

She was a supportive scholar and she published and edited numerous books, book chapters, reviews and catalogue contributions. She curated four exhibitions, ran 12 research seminars and conferences, made 22 guest contributions to conferences and symposia, several of these as keynote speaker, and gave 27 public lectures across the world. She taught hundreds of BA and MA students and supervised 20 students to completion of their PhD degrees.

There were numerous recognitions of Dr Behr’s excellence in research, such as fellowships at Wolfson College, and at the Centre for Research in the Arts, University of Cambridge as well as a Leverhulme Trust Research Fellowship.

Dr Behr was described as “a woman before her time, who combined many fine qualities: the rigor and joy of academia as an inspiring teacher and outstanding researcher … Behind her softness and loveliness was an iron will and determination that saw her not only through the many trials in her life, but also through much of her final illness.”

She is survived by her husband Bernard (BCom 1968) and her sons Elijah and Gabriel and their wider family.

Sources: Bernard Behr, Burlington magazine and The Courtauld

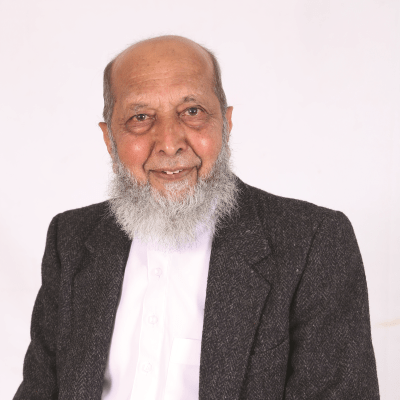

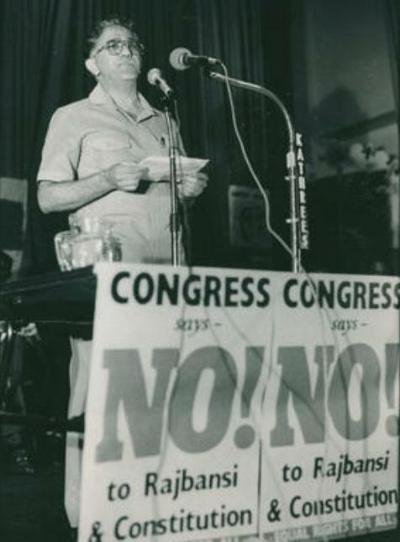

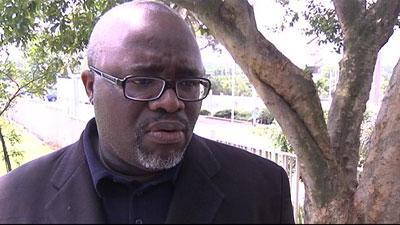

Tiego Moseneke (1962-2023)

Former president of the Wits Black Students’ Society (BSS) Tiego Moseneke (BProc 1989) died on 19 April 2023 in a car accident at the age of 60.

He was born on 8 November 1962 in Atteridgeville in Tshwane, the fifth son of school teachers Karabo and Samuel Moseneke and youngest brother of former Wits Chancellor and Deputy Chief Justice Dikgang Moseneke (LLD honoris causa 2018).

Moseneke attended primary school in his home village of Pheli and high school in Mamelodi. His grades were filled with distinctions, which ensured an easy entry into Wits on a scholarship from Anglo American for a BCom degree, but this was later changed to law. As a result of the Group Areas Act, he lived at the Mofolo Salvation Army Students’ Residence, and later moved to Glyn Thomas House, on the grounds of the Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto. Valuable study time was lost during the daily two-hour commute by bus and after-hour access to libraries “was a pipe dream”.

Absorbing the influence of many student activists at Glyn Thomas, he went on to be elected president of the Black Students Society in 1983 – among others such as David Johnson (BA 1984), Firoz Cachalia (BA 1981, BA Hons 1983, LLB 1988, HDipCoLaw 2003), Chris Ngcobo (BA 1987) and Themba Maseko (BA 1988, LLB 1993).

When the BSS was banned, Moseneke’s resistance to apartheid morphed into active membership of and participation in the United Democratic Front. His activism came at great cost. He was arrested frequently and bore the brunt of violent encounters with the security police. According to the Moseneke family he was detained under emergency regulations for two years continuously and he had frequent asthma attacks while in detention.

With the dawn of democracy, Moseneke was a member of the first Gauteng ANC executive after the unbanning of the party and continued in other senior roles. He set up a law practice, founded the New Diamond Corporation, which partnered with De Beers in diamond mining and exploration, and later New Platinum Corporation, which was sold to Jubilee Platinum. He was founder and chair of the Encha Group, an investment house, at the time of his death.

Moseneke was passionate about intergenerational dialogues between past and current student leaders. He was a founding chairman, along with other Wits alumni, of the South Africa Student Solidarity Foundation for Education, a fund started by a group of former student leaders in April 2016. It led the way in supporting the Masidleni Daily Meal Project under the Wits Food Bank, which provides meals to students from disadvantaged backgrounds and aims to combat hunger and food insecurity on campus.

At his memorial service, held at Wits on 31 May 2023, former Wits SRC members spoke fondly of him: “He stressed innovative ways of addressing the annual fees crisis. Most importantly, he gelled well across generations. I never felt less wise when conversing with him — yet every moment was an opportunity to learn from him,” said Mpendulo Shakes Mfeka, SRC President 2021/22. “When we were slandered, shunned and demonised as hooligans, Tiego reached out a protective brotherly arm, provided a listening ear and empathetic words of comfort,” said Shafee Verachia, SRC President 2013/2014.

He is survived by his wife Koketso and children Didintle, Mooketsi and Pako.

Sources: Wits archives, Moseneke memorial

Andrew Robertson (1943-2023)

Dr Andrew “Andy” Robertson (BSc Eng 1966, GDE 1977, PhD 1977) the founder of mining industry geotechnical and environmental engineering services company Robertson GeoConsultants and co-founder of engineering consultancy SRK Global died on 29 March 2023 at the age of 79.

Dr Robertson was born in 1943 in Pretoria, South Africa, where he was exposed to mining from a young age. In 1966, he graduated with a bachelor of science degree in civil engineering as well as a doctorate from Wits.

In 1974 he, along with Oskar Steffen (BSc Eng 1961, MSc Eng 1963, PhD 1978), and Hendrik Kirsten (BSc Eng 1963, MSc Eng 1966, PhD 1986), formed Steffen, Robertson & Kirsten (SRK) in Johannesburg, the only consulting firm in Africa to specialise in mining geotechnics at the time.

Four years later in 1977, Robertson moved to Canada to start the first international branch of what became SRK Consulting. Several offices in the United States were formed under his guidance. In these early formative years of the company, he provided strong guidance and mentorship to many young engineers and geoscientists. Many went on to develop distinguished careers within SRK as well as other consulting or mining companies. Today, SRK has over 1600 employees worldwide in 40+ offices.

In addition to SRK, Dr Robertson developed several other companies that serve the mining industry. He supported the development of Gemcom in 1981, the mining industry’s first PC-based exploration database as well as ore deposit modelling, and open pit mine planning software system. In 2012, Gemcom was sold to Dassault Systèmes, owner of GEOVIA.

In 1989, he launched InfoMine, with the vision of making mining information more widely available. He spearheaded the digital strategy that became the cornerstone of the company and under his leadership, InfoMine expanded to include EduMine.com (training), CareerMine (recruitment), and Mining.com (news).

In 1995, he founded Robertson GeoConsultants, a specialised, international mining consultancy based in Vancouver, BC. His consulting practice included serving on several peer-review panels and independent review boards for some of the highest and most challenging tailing dams in the world.

From the 1980s to 2000, Dr Robertson worked on foundational research for the testing, prediction, and control of acid rock drainage (ARD). He was a contributing member of the British Columbia ARD Task Force from 1985 to 1990, which published some of the industry’s first ARD guidelines. He wrote or contributed to industry technical guides on mine waste management, uranium mill waste disposal, and guidelines for the rehabilitation of mines. These guidelines established the foundation for environmental best practices in the industry.

His interest in raising industry standards was a pervasive theme through his work. He was instrumental in pioneering the use of failure mode and effects analysis —one of the first systematic techniques for failure analysis—and multiple accounts analysis for engineered solutions in the mining industry. In the late 1990s, he published several papers that are still referenced today in the mining industry.

During his career, Dr Robertson worked tirelessly to protect the environment, communities, water quality, and water supplies. He leveraged his background in rock mechanics, geotechnical engineering, and geochemistry to raise the bar for environmental stewardship within the industry and for the work products he delivered.

Dr Robertson was passionate about improving the design, construction, operation, and closure of tailings dams. To make tailings dams safer, he advocated for improving the technology used for the design, construction, and long-term stability of tailing dams; for fiscal responsibility in the construction and operation of these dams; and for governance so today’s designs account for the needs of future generations and changes in societal expectations.

Beside his brilliant mind, business acumen, and ability to spot talent, he was also admired for his humility, kindness, and generosity. He was always willing to share his knowledge through publications, courses, and countless meetings and discussions. His legacy will live on in all the engineers and scientists he has mentored over his remarkably long and successful career.

Source: SRK Global

Barry Orlek (1949-2023)

Dr Barry Orlek (BSc 1971, PhD 1976) died on 11 March 2023, at his home in Epping, England, after a long battle with myeloma.

He was born in Vereeniging, matriculated from General Smuts High in 1966, and obtained a bachelor of science degree in industrial chemistry in 1971 as well as his doctorate in organic chemistry in 1976 from Wits.

In 1977 he moved to the United Kingdom to take up a postdoctoral position at City, University of London, under Professor Peter Sammes, where he undertook research on the chemistry of beta-lactamase inhibitors. He joined Beecham Pharmaceuticals (now GlaxoSmithKline) in 1981, working as a medicinal chemist on several different drug discovery research programmes until his retirement in 2008.

During his retirement he spent many hours pursuing his passion for photography – both behind the lens and at exhibitions in the UK and abroad. It’s a passion he shared with his wife Ilana. He maintained strong ties with South Africa, visiting every year to see family and friends and to spend time in the bush.

He leaves his wife Ilana and sons Jonathan and Alex.

Source: Orlek family

Cecilia Sentson (1966-2023)

Cecilia Sentson (BSC 1989, BCom 1990) was born on 31 May 1966 and died on 12 May 2023, days before her 57th birthday.

She started her primary school career at St Theresa’s Convent in Coronationville in 1972, where her love of learning and reading was nurtured. She proceeded to St Barnabas High School and matriculated in 1983.

She studied at Wits, completing a BSc in information systems and thereafter pursued a BCom honours degree. She was awarded a scholarship to study towards an MBA at City University in the United Kingdom.

On her return to South Africa, she was appointed as senior lecturer in the school of computer science and applied mathematics for several years.

She was employed by Gemini Consulting as a strategy consultant, by Coca-Cola Group as its head of Information Technology Strategy and executive for Africa and the Middle East.

Her entrepreneurial journey started several years ago and involved the establishment of many ventures which culminated in the creation of her company which she aptly named Neland Consulting, in honour of her maternal grandmother.

She had a larger-than-life personality.

Percival Douglas Seaward (1931-2023)

Dr Percival Douglas Seaward (MBBCh 1954) died on 12 March 2023 at the age of 91 in the United States. He was born on 18 October 1931, the son of Percival and Mary (née Napier Charles) Seaward in Kimberley, Northern Cape.

Seaward matriculated from St John’s College in Johannesburg and completed his MBBCH at Wits. After interning at Edenvale Hospital, he went on to become a district surgeon for a brief period before embarking on a 24 hour-mobile-doctor-on-call position in London, England.

He returned to South Africa and joined the Pneumoconiosis Research Unit, which later became South Africa’s National Institute for Occupational Health. He elected to become a general surgeon, starting as a registrar in surgery.

During this training he published an innovative procedure for treating portal hypertension as well as a treatise on trauma to the neck. He obtained his Fellowship from the College of Surgeons of South Africa in 1968, winning the Douglas Gold Medal for Surgery.

Seaward immigrated to the United States in 1979, initially to Lake Charles, Louisianna, as a general surgeon before relocating to Cleveland, Ohio. He was admitted as a Fellow of the American College of Surgeons in 1980. In Cleveland he also practiced general surgery at the Kaiser Permanente and later concurrently at the Cleveland Clinic.

After retiring from clinical medicine (as a surgeon) he practiced cosmetic laser surgery for a few years before joining Consultants to Government and Industry Incorporated for many years, reviewing surgical health insurance claims.

He was married to Patrica, née Drummond, for 49 years. He was loving father to Gareth (MBBCh 1979, MMed 1990) (Gail) Seaward, Jennifer Bayless (Kirk), and the late Marion Harrison; step-father to Grant Vergottini, Neil (Denise) Vergottini, Kim Vergottini; grandfather of Douglas, Guinevere, Alexandra, Kyle, Nico, Enzo and great grandfather to five.

Source: Seaward family

Felicity Eggleston (1937-2023)

Felicity Eggleston, previous assistant registrar at Wits from 1981 until retiring in 1997, passed away peacefully on the 8 May 2023 aged 86 years.

Felicity was fiercely loyal to Wits, pouring over her alumni magazines as they arrived. She was much valued and respected by top management and vice-chancellors, touching their lives as well as those of SRC representatives and students.

She joined the University at the end of the MacCrone era and listened to farewell speeches for him, Professors Bozzoli, du Plessis, Tyson and lastly Professor Charlton. During her tenure she saw student numbers double in size and Wits expand onto West Campus. She had a strong sense of justice and had multiple memories of picketing along Jan Smuts Avenue in protest against government discriminatory action, with staff linking arms on the university perimeter, their backs to the police and students on the inside.

She started working at Wits in 1968 as secretary to the deputy academic registrar and stayed at Wits in various capacities until her retirement in 1997 having served Wits for almost 30 years.

- 1969 senior clerk and personal assistant to academic registrar

- 1972 secretary of faculty of arts for 5 years

- 1977 invited back to central administration to oversee 10 Faculty offices, and then ran the senate secretariat for many years.

- 1978 Appointed senior administrative officer

- 1981 (Senior) Assistant Registrar (Academic)

- 1990 Head of Faculty Administration and Senate Secretariat

Following her retirement, she started work as registrar of St Augustine's College in Jan 1998, establishing the new Catholic university which opened 13 July 1999. She retired 11 years later after seeing her first students graduate in 2011/2012. She also assisted the Sandton Democratic alliance in 2010.

She played hockey for KZN as a university student, was a birder, climber, hiker, campaigner, feminist, inveterate traveller. Her travels included:

- Climbing mountains in UK, Europe (including the Matterhorn), Namibia and many Magaliesburg and Drakensberg peaks;

- Numerous solo travels in Europe in the late 1950s, early 1960s. Here she had numerous temporary jobs including honing her skills working with the Co-coordinating Secretariat of National Student Unions in Holland, Geneva World University Service and living in and working for the Translation Bureau of the Turkish State Planning Organisation for a year;

- Machu Picchu as part of a base camp expedition then on to travelling through South America for three months;

- Botswana numerous times resulting in her involvement in Okavango conservation for a period; and

- Numerous archaeological trips locally as well as Ethiopia, Tunisia and Egypt.

She hosted wonderful dinner parties with a vast circle of friends including work colleagues who became dear friends. Indeed her friendship circle was so wide she seldom needed to stay in a hotel whilst travelling anywhere! She was gentle kind, courteous and “proper” lady who always managed to smile and had a positive attitude towards everything even in her later years.

She leaves a nephew and three nieces. Two of her nieces, their spouses as well as a great nephew and niece are also Wits graduates.

Source: Caroline Reuss, née Harte (BSc Nurs 1987)

Joseph Pamensky (1930-2023)

Joseph Leon Pamensky – or “Papa Joe” (CTA 1953) – died on 8 March 2023, in Johannesburg after a long battle with dementia at the age of 92.

Pamensky was born in Port Elizabeth (now Gqeberha) on 21 July 1930 to jewellery store owners Samuel and Freda Pamensky. He attended Grey High School, excelling in maths and playing first team cricket, where he opened the innings and kept wicket.

Pamensky studied as a chartered accountant at Wits and played club cricket for the university and, later, at Pirates in Johannesburg. Dr Ali Bacher (MBBCh 1967, LLD honoris causa 2001) remained a life-long friend and colleague.

Pamensky served on the Wits All Sports’ Council as a student and was elected to the Transvaal Cricket Union’s junior board as a 23-year-old in 1953 before being elected to the full board two years later. On the Transvaal board, he served as vice-chairperson, chairperson, treasurer – and, eventually, president. His election onto the South African Cricketers’ Association board followed in 1967. He was one of the drivers of the negotiations which lead to the formation of the South African Cricket Union in 1976 and was its president until 1991. He was one of the “main drivers of the short-lived unity process in the mid-1970s and, as honorary president, was supportive of Dr Bacher becoming Transvaal cricket’s first full-time chief executive in 1981.

During the 1980s, with the national team banned from international competition after the cancellation of the proposed tour to Australia in 1971/2, Pamensky, Bacher, and fellow administrator Geoff Dakin initiated the controversial “rebel tours”. This resulted in English, Sri Lankan, West Indian, and Australian tours to the country.

In 1987, Pamensky received the Order of Meritorious Service Gold Medal by the South African government. He was also a member of the SA Institute of Chartered Accountants (Chartered Accountant of the Year 1984) and an honorary life member of Melbourne Cricket Club as well as Cricket South Africa and Gauteng cricket.

Seven years ago, Pamensky was diagnosed with dementia. He had remarried after the death of his first wife Pamela, nèe Goldberg, 14 years ago.

He is survived by his second wife Jackie, children Kevin (BA 1986), Martin and Beverly.

Sources: Archives, Cricket South Africa, South African Jewish Report

Mark Pilgrim (1969-2023)

Veteran South African broadcaster Mark Pilgrim died on 5 March 2023 at the age of 53, after battling stage four lung cancer.

He was born in England and moved to South Africa at the age of nine, matriculating from Sasolburg High School. He started his studies at Wits in 1987, completing two years towards a bachelor of commerce degree, which he never completed. Instead, his interest in radio was sparked on the campus radio station Voice of Wits. This followed many successful years at various radio stations such as 5FM, 94.7 and KFM.

In 2014 he joined a new station Hot 91.9 FM in Johannesburg, and in 2015 won the MTN Radio Award for Best Weekend Radio Show. In 2019 he won the Liberty Radio Award for the Best Daytime Show in South Africa and in 2021 he was inducted into the South African Hall of Fame for his contribution to the industry.

The radio DJ won multiple awards throughout his career and the South African radio industry honoured Pilgrim by inducting him into the Radio Awards Hall of Fame in July 2021.

He married Nicole Torres in 2007 and after almost 13 years together, divorced in 2020. They had two children, Tayla-Jean and Alyssa, together.

Pilgrim also ventured into TV in 2001 when he was host of the first season of Big Brother South Africa. In 2002 he returned to host the second season, and in 2003 he hosted the first season of Big Brother Africa. He worked as an MC and motivational speaker and was an advocate for positivity, inspiring others with his own experiences. He published his autobiography, Beyond the Baldness (Tracey MacDonald Publishing, 2015) and from 2013 to early 2016, he wrote a monthly column about parenting from a dad's perspective for Living and Loving magazine.

Pilgrim was diagnosed with aggressive stage 3 testicular cancer, which spread to his lungs and kidneys, in 1988. He was 18 years old. After 33 years in remission, he was diagnosed with stage 4 lung cancer. In June 2022 he revealed that the cancer had spread to his femur, the base of his spine, and his lymph nodes. He launched a YouTube video series chronicling his treatment.

He was discharged from hospital, two months later, in time to ring in the new year with his fiancée, Adrienne Watkins.

Sources: News 24 and Wits archives

David A Lipschitz (1943-2023)

Dr David Lipschitz (MBBCh 1966, PhD Med 1973) affectionally known as "Dr David," passed away on 6 March 2023 surrounded by his family. He was born in Johannesburg, the eldest of four children. Ever the entrepreneur, he once dug up all the plants in his father's garden and attempted to sell them on the roadside. Luckily, he moved beyond his mischievous ways and went on to study medicine at Wits.

Following in his father's footsteps, Dr Lipschitz emigrated to the United States in 1972,

training as a haematologist at the University of Washington and doing the seminal research in the development of the serum ferritin assay, a tool that is still used to help evaluate iron levels in blood. After stints at Montefiore Medical Centre and Kansas University Medical School, he joined the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences (UAMS) as director of the Division of Hematology/Oncology.

Dr Lipschitz flourished in Little Rock. He began research on the effects of nutrition on aging, which led to a lifelong focus on the unique medical needs of older people. In 1995, he assumed the position of director of the Centre on Aging at UAMS. Under his leadership, UAMS received $30.2 million from the Donald W. Reynolds Foundation to establish the Donald W. Reynolds Department of Geriatrics and the Institute on Aging. He went on to facilitate the development of a state-wide network for geriatric care, ensuring that every older Arkansan had access to high quality medical care.

While Dr Lipschitz was an exceptional leader in medical research and administration, his greatest passion being educating his patients and the public about healthy aging. He often said, "Everything you've been told about growing older is wrong!" Through his weekly newspaper columns, radio shows and television segments, he empowered people to live each day to the fullest. Well before "body positivity”.

He never missed an opportunity to crack a corny joke, hum a made-up tune, or dance as if no one was watching (though clearly everyone was!). This voracious appetite for life also meant he was never afraid to put a fork on someone else's plate – resulting in a whole generation of speed eaters. He was endlessly devoted to his three French bulldogs, Barkley, Mochi, and Peaches. They were expertly trained to sleep in a pile on his lap while he watched murder mystery shows for hours.

But most of all he loved his family, his wife, Francie, who he said was the most brilliant mother and physician in the world; his six children, Andrea, Elan, Howard, Riley, Forbes, and Evan; and his grandchildren.

Source: Arkansas Gazette

David L James (1927-2023)

David Leslie James, known as “Dave” (BSc Mech Eng 1950, BSc Elec Eng 1952) was born in 1927 and he lived his early childhood in mining company towns on the Witwatersrand such as Robertson Deep, Sub Nigel and Vogelstruisbult.

He went to primary school at Pridwin Preparatory School and later became a boarder at Michaelhouse in Natal, which he enjoyed, especially being set free to wander around the countryside on a Sunday. His family owns a letter he wrote to his mother at the time: “Dear Ma. Please send a small frying pan, some tins of bully beef and some small blocks of jellified methylated spirits. Love, David.”

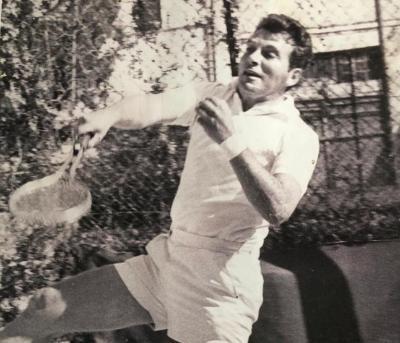

In 1945 he started an engineering degree, but quit after about a month when he found the syllabus replicated what he had done the year before in sixth form and joined the war effort, stationed at the naval base in Saldanha Bay. The following year he resumed his studies at Wits, where he met his wife, Jenepher, in 1948, at a tennis party. He graduated with a BSc Mech Eng in 1950, and then with BSc Elec Eng in 1952. He started his master’s degree, working under the supervision of Costa Rallis (BSc Eng 1947, MSc Eng 1948, PhD 1963, DSc honoris causa 2003. He married Jenepher (DipArch 1967) in February and they went to live in the married students’ quarters at Cottesloe. That’s where they met many of the people who became lifelong friends, like Tony and Joy Eagle and Dorothea and Gerald Zeffert (DipArch 1954).

James worked for the Centre for Scientific and Industrial Research briefly and then joined the Physics Department at Wits, where he worked as a lecturer for about 40 years, mainly teaching students in electrical engineering. He was much loved and much appreciated by his students, one of whom observed that he was “one of the last of the old school of dedicated university teachers, unappreciated and undervalued by the authorities, who rendered enormous service to the generations of undergraduates they taught”.

In his leisure time he built boats, took groups of students and his family on skin diving and camping holidays in Mozambique, and eventually – after retirement – politely turned down an offer by the Physics Department to continue as a lecturer, and completed the building of a boat which he then sailed to the Comores, Madagascar and up the east coast of Africa as far as Kenya. A former Wits colleague described James as a “cross between Scott of the Antarctic and a slightly older version of a hippy – a sort of glorified tramp. Never happier than when sailing somewhere, travelling across the most inhospitable terrain of Lesotho or camping on some beach on which no-one has previously set foot.”

After restoring the Stillbay holiday house that had belonged to his grandfather, he and Jenepher spent the last years of their retirement there.

He kept in touch with his old friends, especially John Crawford (BSc 1959) and Eddie Price (BSc Hons 1960), both of whom predeceased him.

He died on 14 February 2023. He leaves Jenepher, four children – Deborah (BA 1975, BA Hons 1980, MA 1988, PhD 1994), Nicholas (BSc Eng 1981, GDE 1985), Simon (PDipEd 1986) and Melissa (BA 1986, BA Hons 1987) – and nine grandchildren.

Source: Deborah James

Phil Levinsohn (1939-2023)

Chairperson of the Press Council of South Africa Judge Phillip Levinsohn (LLB 1963) died on 21 February 2023 at the age of 83 after a brief illness. He practised as advocate of the Durban Bar from 1971 and took silk in 1988. After a respected career at the Bar, he was appointed as judge of this division in 1990. In 2006 he was appointed as Deputy Judge President of the division, a post which he held until his retirement on 23 August 2009. He contributed widely and followed the affairs of the Bar both locally and nationally and served for many years on the National Bar Examinations Board throughout his time and into retirement.

He was described as "a gentle, caring man who was a fierce defender of media freedom and a passionate believer in fair media coverage as espoused by the Press Code

He is survived by his wife Phyllis, and children Deborah, Jacques, Gideon, and Adam.

Sources: The South African Judiciary, News24

Brian A Lieberman (1942-2023)

Professor Brian Abraham Lieberman (MBBCh 1965) passed away on 20 February 2023.

Professor Lieberman was born in Johannesburg and educated at Grey College in Bloemfontein from 1955-1959, and he obtained his degree in medicine from Wits in 1965. He moved to London in 1971 to take up a post at St Mary's Hospital. There he specialised in laparoscopic sterilisation, on which he published a number of research papers from 1974 onwards including in the Lancet in 1976.

Professor Lieberman took up a post at St Mary's Hospital in Manchester as a consultant obstetrician and gynaecologist in September 1978. Inspired by the early work of fertility pioneers he established the world's first publicly funded IVF unit at St Mary's in 1982. He founded the Department of Reproductive Medicine and remained medical director until his retirement in 2007. He also established the private Manchester Fertility Services clinic in 1986 and remained a director until 2009.

Professionally, Professor Lieberman made extremely important contributions to the field of IVF from the early days onwards. He was a leader in the development of clinical practice in IVF, fertility preservation, embryo research and embryonic stem cell biology. He founded the National Egg and Embryo Donation Society, the forerunner of the National Gamete Donation Trust. Professor Lieberman wrote over 100 academic papers and numerous textbooks and chapters over a research career from 1969-2011. He was made an honorary professor at the University of Manchester in 2006 and an honorary member of the British Fertility Society in 2018.

He was instrumental in the careers of many in reproductive medicine. To his enormous credit, he placed great value on the expertise of others and particularly enjoyed surrounding himself with people who in his words “know things that I don't”. In that respect he was an excellent leader.

Professor Lieberman had many interests outside of academia, including a long-standing interest in African art and travel in the African continent, including an overland trip to climb Mount Kenya to raise money for charity. He was a keen sportsman, representing his school at rugby, cricket and swimming. In later life, he became an avid golfer and is now buried as close as possible to the eighth hole at his golf club. He was an avid Manchester United fan, and a season ticket holder.

He is survived by his wife, Bernice, and three children.

Source: Professor Daniel Brison

Peter Davey (1953-2023)