Understanding the infodemic

- Deborah Minors

Covid-19 misinformation, mythology, and fake news has implications for public health.

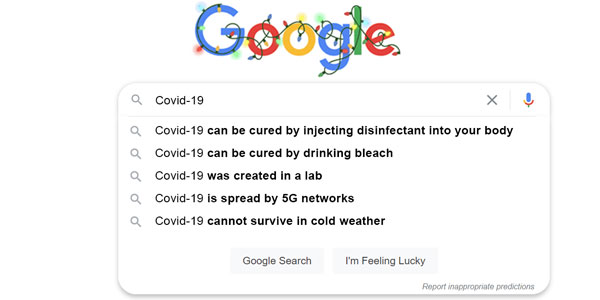

Did you hear the one about injecting bleach to stave off Covid-19? Perhaps you forwarded that WhatsApp message your uncle shared about drinking ethanol for immunity? No doubt you’ve encountered ‘viral infection by 5G’, ‘dolphins frolicking in Venetian canals’, or know someone who believes the virus was made in a lab.

Along with a lethal virus, the Covid-19 pandemic has unleashed a tsunami of information, misinformation, myths and fake news that the World Health Organization (WHO) calls an “infodemic” – this is an over-abundance of information including deliberate attempts to disseminate wrong information to undermine the public health response and advance alternative agendas. So serious is the infodemic that the first WHO Infodemiology Conference took place in 2020.

‘Mythinformation’ and folklore

In Africa, our own infodemic emerged. “Myths doing their rounds in Africa were the belief that SARS CoV-2 does not affect Africans, which was fuelled when a Cameroonian student who contracted the virus in China responded well to treatment,” says Dr Neelaveni Padayachee, Head of Clinical Pharmacy, who researches pharmaco-vigilance and rational drug use and who delivered a podcast on coronavirus conspiracies and myths.

“Another popular myth was that the virus will not survive in the warm African climate – this has been shown to be untrue – and the myth that spraying alcohol and chlorine all over your body will protect you from the virus.”

These myths emerged from an explosive collision in SA’s socio-political and cultural milieu at the heart of which is the question: who do you trust?

Professor of Sociology David Dickinson says that sometimes misinformation happens simply because people misunderstand something.

“People make a mistake, and it’s common in a complex situation such as the Covid-19 pandemic. For example, references to ‘the Covid-19 bacteria’, when in fact it’s a virus,” he says. In this case there is no malice or intent to misinform, but the public health implications are profound.

Early in SA’s Covid-19 pandemic, Dickinson assembled an impromptu focus group in the townships he frequents for his research, to test the myths that erupted almost immediately.

“In my conversations in the townships I’ve been struck by how early on in the pandemic these beliefs emerged, and how fluid the alternative theories were. Myths are the way that people try to make sense of things – myths like ‘the virus was made in a lab’,” – which, Dickinson points out – is also a myth that emerged during the HIV pandemic.

“Folk theories and lay theories about HIV, which are linked to bodies of knowledge about traditional healing and ‘global control by Bill Gates’ are genuinely held by people. They have constructed it as ‘the truth’ and it’s not a mistake,” he says.

In his book, Myths or theories? Alternative beliefs about HIV and AIDS in South African working class communities (2013), Dickinson writes that folk and lay theories [of HIV/AIDS] are also often highly palatable in that they provide hope and comfort in terms of prevention, cure, and the allocation of blame.

“Covid beats HIV hands down in the area of folk theories operating. However, this happens because science doesn’t have an answer to Covid-19, so then you have license to make up your own.”

“We need to ask: What’s the underlying concern? The 5G beliefs stem from concerns about technology and its perceived threat to job losses or personal freedom, for example”.

Fake news and the kernels of truth

Much maligned but fundamental to taking pandemic parlance to the people, the role of the media cannot be under-estimated. Glenda Daniels, Associate Professor in Media Studies at Wits, says: “Lies travel faster than facts, research has shown. People should find credible news sources where news has been checked,” – although she concedes that within the media sector, fact-checking functions are not at the same level that they used to be, a fact borne out in Wits Journalism’s State of the Newsroom report (2018). Daniels says, “It’s hard for everyone to work out what is fake news and credible sources, but there are huge initiatives in the country and around the world to help the public.”

Lee Mwiti, Chief Editor at Africa Check, a fact checking non-profit in Wits Journalism, says: “Misinformation with the broadest reach is that which has a kernel of truth embedded, rather than that which is fabricated. It is worth remembering that myths are consequential, they have a real impact on people's health, relationships and safety.”

Ina Skosana is the Health and Medicine Editor at The Conversation Africa through which university academics share factual and accurate research with the public. She says myths and misinformation are common in a crisis – as seen during the Ebola outbreak. “Science communication experts identified fear and the speed of social media as contributing factors,” she says.

The post-truth era

“Communication is complex and contextual,” says Leigh Crymble, a doctoral student in Behavioural Economics at Wits Business School, who is researching language, ideology and behaviour in relation to broader social, psychological, and economic structures of society.

“We are now living in what many call the ‘post-truth era’, where critical, active consumption of information is so important. The tricky thing is that we’re used to trusting people close to us, but research is increasingly showing that these are often the people sending us misinformation. Because our immediate behavioural reaction is to trust the sender, we often get caught up in misinformation.”

Crymble says that the key to diffusing fake news is to repeat the facts continually and consistently across platforms in ways that don’t allow for conflicting messages.

Building trust during a pandemic

How do we communicate to save lives during a pandemic? Professor Jennifer Watermeyer is Director of the Health Communication Research Unit at Wits. In her book, Communicating Across Cultures and Languages in the Health Care Setting: Voices of Care (2018), Watermeyer writes that metaphors can be essential and empowering in healthcare communication. They can be tools of cultural brokerage for the “discourse of the unsayable”.

“In the case of the Covid-19 pandemic, metaphors have emerged to explain concepts such as contagion – coronavirus is like ‘glitter’ or a ‘forest fire’. If used correctly and chosen appropriately, metaphors can be useful for explaining difficult concepts,” says Watermeyer.

Metaphors can go wrong, however. “We have seen the dark side of this in the case of HIV/Aids, where there may be confusion around terms such as positive/negative. With Covid-19, battle or violence metaphors have the potential to legitimise authoritarian response and lockdown measures.”

Watermeyer says that simple, time-sensitive, proactive communication that focuses on what is known and not known during a pandemic engenders trust.

Trust comes from what Aviva Tugendhaft calls “deliberative engagement”. Tugendhaft is a Senior Researcher in the SAMRC Centre for Health Economics & Decision Science - PRICELESS SA. She and colleagues published research on the modification of a public engagement tool, a board game called CHAT (Choosing All Together).

“When the legitimacy of the decision-making process is questioned, it results in low levels of public trust, even if many measures to address the pandemic are evidence-based,” says Tugendhaft. “Meaningful engagement goes deeper. Tools like CHAT are ‘deliberative’ – they start with a shared knowledge base and empower people to make informed decisions as a group.”

Flattening the infodemic curve requires us to understand the origins of information and extract the kernels of truth. Public health communications must be consistent and accurate. It is only through engaging deliberately with each other and with the facts that we can learn to trust and share the information that keeps us alive.

Digital hygiene

With fake news proving to be a real threat to our health, it’s important for us all to keep our news reliable by practising digital hygiene in the same way we do physical hygiene. Dr Leigh Crymble provides some tips for digital hygiene:

- Source: Check to see if the news is also being reported on mainstream sites. If the source is “a friend of a friend”, treat it as a rumour and discard it.

- Content quality: Credible news sites are less likely to have typos, spell things incorrectly or use poor grammar. Text in colour, capital letters and the overuse of exclamation marks should also make you suspicious.

- Encouraging you to share: Fake news thrives when it’s shared. If the message asks you to forward it to your network, be wary. Remember, fake news can only spread if we spread it.

- Report fake news: Fake news about Covid-19 is now a criminal offence in South Africa. If you receive information that you suspect to be fake news, take a screenshot or copy the link and report it to fakenewsalert@dtps.gov.za or WhatsApp 067 966 4015.

- Deborah Minors is Senior Communications Officer for Wits University.

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the 11th issue, themed: #Viral. Inspired by the SARS-CoV-2 global pandemic, content relates to both the virus that causes Covid-19, as well as the socio-economic, political, and environmental ramifications.

Fact checking tools and sources

- Africa Check: How to Fact Check: https://africacheck.org/how-to-fact-check/

- https://sacoronavirus.co.za

- The Conversation Africa WhatsApp service to help stem misinformation around the virus:

- South Africa: +27 76 771 2387

- Kenya: +254 741 976111

- Ghana: +233 541 946552