Fractured histories

- Tamsin Oxford

Coloured women find their centre beyond the whisper and gossip.

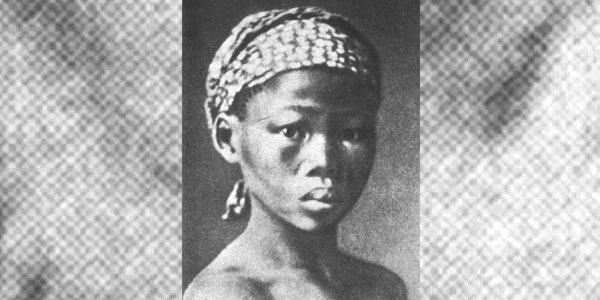

Krotoa, the first matriarch of the Cape

The story of the coloured women’s dispossession in South Africa circles back to Krotoa, the first matriarch of the Cape. Krotoa was a Khoi translator and mediator for the Dutch in the 1650s when they began their colonial conquest of the Cape.

Krotoa was not only a domestic worker, but an interpreter and a mediator – a woman so trusted that she helped make peace when war was breaking out. She was only 16 when she negotiated peace between the warring factions of the ‘Hollander and Hottentots’ in the 1600s.

Hers is a powerful and impactful lineage that came to a sad, marginalised end when her intelligence, gifts and forceful nature should have given her a rich future. Krotoa was a powerful woman whose history was lost by time and colonialism.

Dr Darlene Miller, a Senior Lecturer in the Wits School of Governance, is currently conducting research that traces Krotoa’s lineage. Through her research, Miller contends that the loss of this lineage – and that of other Khoi or coloured women – is a situation affecting many South Africans who are classified as coloured. This loss of lineage has implications for coloured women’s leadership, and the unique experiences that come with being a woman of Khoi descent.

An eviscerated history

“The first difficulty is that you don’t exist,” says Miller. “When you don’t have an active past, you exist in the present without it, and the truth is that the past is a gift. It is an ancestral river that has been eviscerated by the historic actions of others.”

This is a scenario that many other cultures in South Africa cannot imagine. Yet exploring an archive as a coloured woman means being surrounded by rows and shelves of books that trace the lineages and histories of white families while the microfiche films of coloured births and deaths have been erased.

“I can’t even find a record that my grandmother existed,” says Miller. “There is no lineage, record or lists of birth and deaths, a very common experience for coloured people. We don’t find ourselves in the archives because our ancestors struggled to acknowledge our existence. We were the dirty little secrets stuck onto a part of the farm where we could not be seen and recognised as the child of the patriarch who sired us. We were a whisper and a gossip, our history erased.”

Biographical impoverishment

When a person doesn’t have a written or verbal record of their lineage – this link to the land through their history – then they lose out on the spiritual and symbolic connections to their past. For Miller, many black South Africans still have some connection to the land and many can trace back to their ancestral homes and lineages. However, being a descendent of the Khoi is a complete dispossession – mixed race parentage with no history on either side.

“It is defined as umbilical ontology, where coloured women end their days without the knowledge of their lineage in a sort of biographical impoverished existence,” says Miller. “Your life is writ small. If you have the awareness of this loss, then this tends to express itself in learned cultural habits like alcoholism and substance abuse. This is a far way to fall for a culture that’s highly articulate and intelligent. Many of the Khoi were poly linguistic with immense talent, and the removal of their history means that many people of this descent are having to make do with a montage made from the fragments of the past.”

Lost leadership legacy

For Miller, it is critical that coloured women reclaim who they are so that they can fulfil their leadership potential. The value of this can be seen in the powerful confidence of strong African women leaders – self-possessed and self-confident, they are comfortable within themselves and their histories, not concerned about the criticisms they receive. This, Miller feels, is a gift taken away from coloured women and one that requires that they take a different route to achieve that sense of self-possession and ancestral purpose.

“Coloured women need to acknowledge their pasts and their lineages and traditions, this will give them the stories that they need to dig deeply into their histories and build their cultural traditions,” says Miller. “This can be done by listening to the stories, African storytellers, and realising that your past is a powerful route to confidence and understanding.”

Miller believes that coloured women are amazing and captivating storytellers. “Somewhere in your psyche is a story,” she says. “We would do this in the past around the fire when the moon was rising, capturing the rhythms of life within the stories. We need to recapture our history by finding the storyteller within, and then reconstructing the damage of our lineage.”

In most cases in the past, these women ended up as marginalised and incarcerated, especially the powerful and beautiful ones. “Avoiding tragedy is difficult. But ultimately, coloured women now sit at the cusp of change, where they can leave behind the strictures of European lineages and stories, and find their own within the fractured histories that still exist. And, in finding these, find the centre of themselves.”

- Tamsin Oxford is a freelance writer.

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the 13th issue, themed: #Gender. We feature research across disciplines that relates to gender, feminism, masculinity, sex, sexual identity and sexual health.