Cheers to SA’s most pervasive drug

- Shoks Mnisi Mzolo

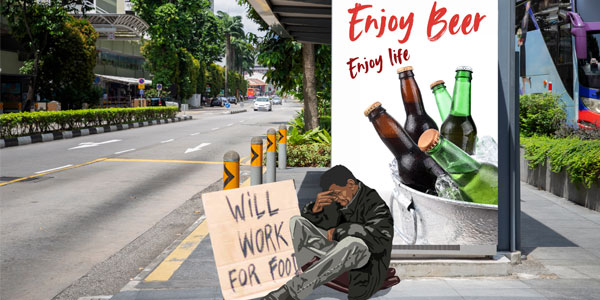

Alcohol is so ubiquitous and its marketing so pernicious that there’s a tendency to underestimate its impact on public health. So, why do we drink?

Cool and hip youngsters glowing with good health and living the high life grace a billboard at Johannesburg’s Maponya Mall. The thirst-inducing billboard extols some recently introduced ‘extra smooth’ beer. Of the 28 billboards with prime locations along a 10-minute drive on the M1, five sell beer, whiskey, and brandy. Further, about 10 alcohol adverts per hour are beamed to SA households during primetime TV, united in their silence on its toxicity and other harms.

Dangerous daily sundowners

The World Health Organization (WHO) warns that alcohol is a toxic, psychoactive, and dependence-producing substance and that any beverage containing alcohol, regardless of its price and quality exposes drinkers to cancer.

Drinking alcohol daily is toxic and considered a public health red flag. Broadly, tolerable maximum units equate to 10-14 per week. For context, the 750ml bottle of wine (with 14% alcohol by volume) equals 10.5 units of alcohol, while a 440ml beer can (5% alcohol by volume) totals 2.2 units. Thus, the ceiling – to keep harm minimal – is somewhere around a dozen cans of beer or a bottle of wine per week. Expect a dizzying 35 units from a 750ml bottle of brandy. But nobody walks around with a calculator to keep track of units taken. Alcohol is the most pervasive drug in South Africa – and its abuse is alarmingly clear.

Bruise cruise

Alcohol abuse abounds and is at the heart of gender-based violence and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), notably when judgment is impaired, argues Mafuno Grace Mpinganjira, a Research Assistant in the South African Medical Research Council Wits Rural Public Health and Health Transitions Research Unit (Agincourt) in the School of Public Health.

Mpinganjira blames this scourge, in part, on easy access. The sight of intoxicated people and fights breaking out on weekends at taverns, pubs and clubs is common. This underscores Mpinganjira’s assertion that alcohol consumption impairs judgment and triggers an invincibility complex.

“Drinking opens a lot of problems. As with any drug, it is hard to self-regulate. The ground is fertile in South Africa because of the country’s socio-economics set-up,” Mpinganjira says, adding history and socialisation.

Alcoholic infants

The contrast between communities hardest hit by alcohol abuse and the buoyant youth on the Maponya billboard is stark. In the Western Cape at wine farms, the ‘dop’ system of part payment of wages to workers (including pregnant women) in wine, prevailed until it was outlawed in 2003.

As a result of the ‘dop’ system, the Western Cape is the world capital for foetal alcohol spectrum disorder (FASD), which took root in colonial times. It is a condition that condemns unborn children to stunted physical and mental growth. “Regardless of what the law says now, people are unable to just abandon drinking – it’s a behavioural issue,” says Dr Joel Francis, an epidemiologist in the Department of Family Medicine and Primary Care in the School of Clinical Medicine, who advocates that direct interventions extend to neonatal care and that alcohol intake be discouraged during pregnancy.

Labels and mixed messages

While advertising bans and explicit warnings printed on cigarette packs make the dangers of smoking clear, government is ambivalent about alcohol-induced harm, argues Mpinganjira. “We’ve got to stop looking at alcohol consumption in isolation because its effects are extensive. There’s a link to the health side, to the economic side, to societal development,” she says.

Aggravating the ambiguity are those messages that incorrectly but loudly claim that there are health benefits to moderate alcohol intake. Francis, who advocates appropriate labelling of alcoholic drinks, says, “Messaging with alcohol abuse is conflicting. This is a huge industry. It’s an oligopoly of seven companies pushing for aggressive marketing. We are in a place where commercial determinants lead to a conflict of messages.”

Big Liquor vs promulgation

Another source of conflicting messages is the stop-start-stop Liquor Amendment Bill, approved by Cabinet for public comment in 2016, now stuck in the pipeline. In the meantime, East London’s Enyobeni tavern tragedy in June 2022 – where 17 of the 21 youths who died were reportedly underage – demonstrates the urgency for stronger legislation.

Liquor is big business. It sustains jobs in every community, from taverns to high-end clubs. The alcohol industry even has its own Association for Alcohol Responsibility and Education (AWARE) “for promoting the responsible use of alcohol”, according to www.AWARE.org.

AWARE claims to support “sober pregnancies” to staunch FASD and to fight “binge drinking”, which targets people aged 25 to 34. While acknowledging studies that suggest excessive alcohol indulgence affects people as young as 15-years-old, the industry continues to invest billions in sports sponsorships and mints a fortune in government taxes.

Drinking during lockdown

Although promulgation on its own will be no panacea for alcohol-induced social ills, regulation could arguably tame some bad habits. A study by Dr Witness Mapanga, a postdoctoral researcher in the Centre of Excellence in Human Development, found that despite alcohol sale bans during lockdown in 2020, not only did many people polled find access to the bottle, but a third of those who drank “were classified as having a drinking problem that could be hazardous or harmful” and nearly a fifth “had severe alcohol use disorder during the Covid-19 lockdowns”.

Mapanga reckons that short-term gains should not hurt long-term public health. “Surely reduced consumption will lead to a decrease in sales and that could mean job losses. The question that the industry should ask itself though is: what’s ideal? Are suppressed sales and better health outcomes less important than better sales and poor national health? When people drink and smoke excessively, outcomes include several problems,” he says. “Does the industry want healthy and fit customers or a damaged society?”

A damaged society suffers multimorbidity (the presence of two or more long-term health conditions). Professor Xavier Gómez-Olivé, Associate Director at Agincourt, says alcohol use is associated with multimorbidity among adults. The risk of multimorbidity increases with age, and liquor compounds exposure to unprotected sex, multiple partners, and other forms of irresponsible behaviour.

In rural areas, drinking alcohol increases the chances of multimorbidity by 5% (if HIV is included) and by 6% if HIV is excluded. This is according to a Wits study that involved 10 000 participants in South Africa, Burkina Faso, Ghana, and Kenya. The study found that, of the urban communities polled, the highest level of intake was in Soweto where about 71% of males polled drank.

Raising the bar for public health

One of the most effective ways to fight alcohol abuse should involve outlets for messaging and should focus on the youth – but not neglect the broader population, asserts Gómez-Olivé.

“People know about car accidents, STIs and multimorbidity, yet they still drink heavily. Others drink to get drunk. Let’s find out why people drink so much. There’s a lot of poverty and inequality here. In villages without structure, there seems to be higher consumption levels. As we saw with lockdown, forbidding or banning sales doesn’t stop consumption. South Africa is the most unequal country in the world. That brings us to a lot of problematic social issues or family matters.”

Mapanga wants the subject probed further. “We need more research to establish why things are the way they are, to search for interventions. Let us understand the impact of drinking and smoking on adults.”

- Shoks Mnisi Mzolo is a freelance writer.

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the 16th issue, themed: #Drugs, where we highlight the diversity, scope, and multi-dimensional nature of drug-related research at Wits University.