HOME AWAY FROM HOME

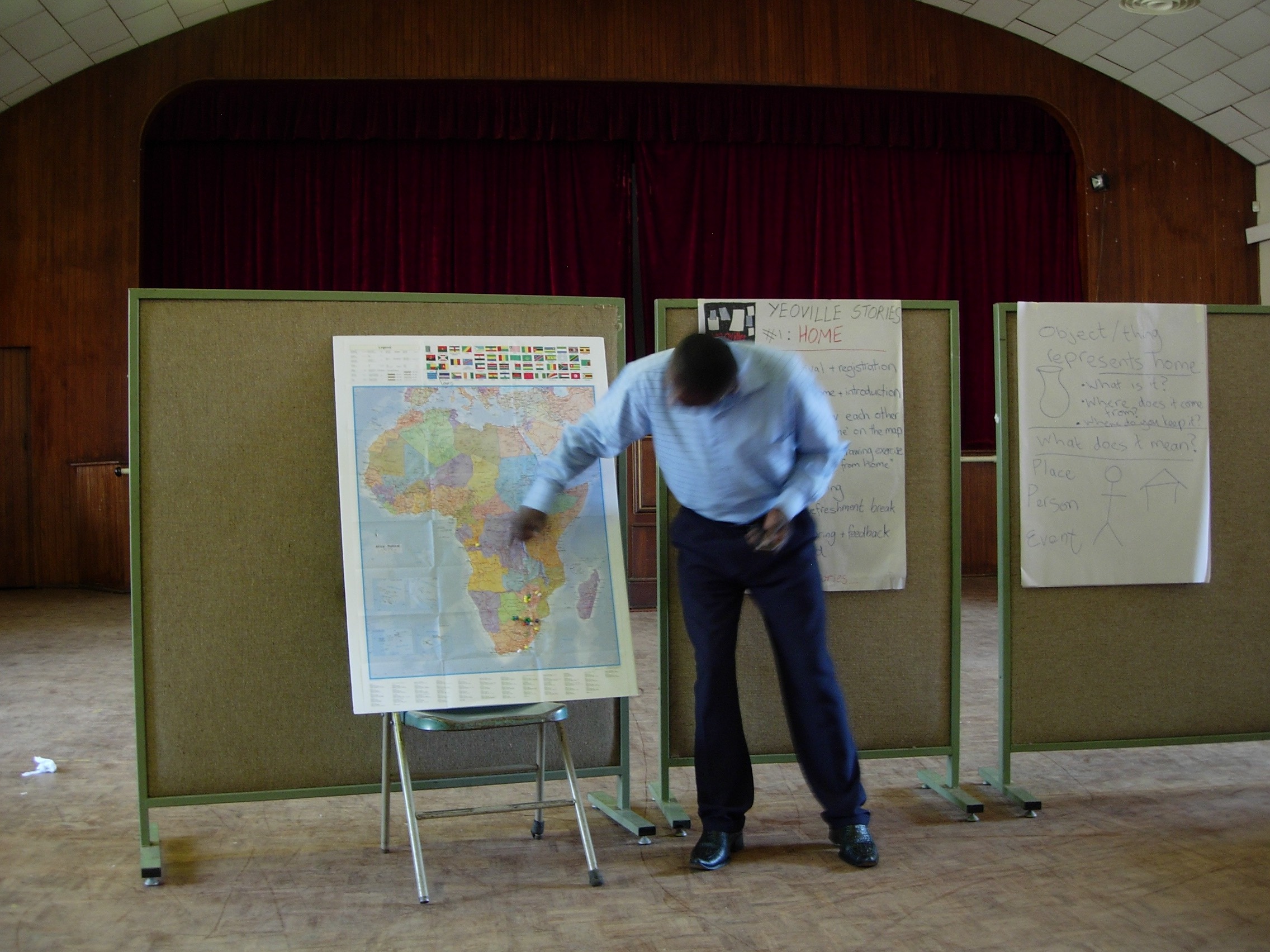

A series of seven « Yeoville stories » workshops conducted by Sophie Didier and Naomi Roux in 2010 explored the residents' relationship with the neighbourhood, their perception of the environment, their memories of arrival in Yeoville, as well as their connections with their place of origin.

They were attended by 15 Yeoville residents: the group was composed of 11 South Africans stemming from the Eastern Cape, Kwa Zulu Natal and Gauteng, and 4 foreign nationals from Zimbabwe, the DRC and Ethiopia. 8 were men and 7 women, the men being overwhelmingly younger (in their twenties mostly). For most of them, the younger ones in particular, residing in Yeoville was often just one stop in sometimes complex life stories and trajectories spanning several countries and provinces of South Africa.

A project facilitated by Sophie Didier and Naomi Roux

Stage 1: at home in the neighbourhood

Our participants were given disposable cameras and asked to photograph some of the sites that held a specific meaning for them, good or bad, intimate or public. This 2 week photographic safari in their neighbourhood was conducted with a series of guidelines : they were to document their home, the spaces that they visited often, the spaces that they avoided, their favored sites of relaxation and recreation, the religious or spiritually significant sites for them in the neighborhood, and other spaces of personal importance. These images were developed, with one set being returned to participants, and a few of them reproduced hereafter, and even though the photographers did not always stick to their shopping list, 15 rolls of film came out of the exercise.

What they tell of the neighbourhood and its appropriation by the residents is a complex tale intersecting the intimate: the cramped space of the room shared, the proud pictures of the grand children..., and the neighbourhood scale: Rockey-Raleigh and its traders, the Shoprite wall and its postings for lodging offers... It is also reflecting age and gender divides, the variety of personal experiences and perceptions as well as the importance of the conditions in which the participants first arrived in the neighbourhood, which durably shaped their apprehension of Yeoville. For those who chose Yeoville as a convenient place due to its proximity to the city centre and its employment opportunities, the moment of arrival and first discovery was less prominent in their photographic essays. For those who arrived after a long and often forced journey across provinces and countries, the place of arrival in Yeoville could take up as much as half the shots in their photographic essay.

The overall tone of the essays also differed greatly from one participant to another: in a couple of essays, our photographers clearly deplored the lack of cleaning services and public safety in the area, while others simply enjoyed documenting their homes and the shops and places they would patronize in the neighbourhood. One could sense here a difference between concerned residents, often involved themselves in local activism, and the rest of the participants. Some of them being in a state of extreme fragility with regards to housing and employment opportunities, they documented mostly the more intimate dimension of their material conditions. Yet, this should not be taken as a mark of disregard for the neighbourhood: they were usually keen when talking about their pictures to link their own experience to that of others and would thus also exhibit a form of collective understanding of Yeoville and its hardships. The photographic essays would always emphasize, in one way or another, the connections the neighbourhood offered and underline its role as a place for community nurturing. Via places of worship and the religious communities, the entertainment spots where diasporas would meet, the relationships between traders and their preferred customers, all the essays showed this potential connection and the impossibility to be alone or lonely in Yeoville.

Despite the diversity of personal situations which reflected in the photographic essay, several traits of the neighbourhood appeared to be shared by all participants. Rockey-Raleigh appeared in almost all the essays regardless of gender, origin, and age of the photographer, as a recognisable feature of the neighbourhood. The shops, the crowds, the bustle of the street were recognized as a key feature which, although at times a little scary, also represented the diversity of the community for our photographers. On Rockey-Raleigh, women tended to shoot the market, the street traders' stalls they would patronize on a daily basis, the recreation centre where they would attend some community activities, as well as, for those of them with a job outside of the neighborhood, the taxi ranks and bus stops that would link them to the rest of the city. The men, younger and for the most part unmarried, were more likely to shoot Times Square or the Rasta House as a place of entertainment, as well as specific diasporic watering holes such as Kin Malebo. The churches and places of worship were also very prominent, as an important part of the weekly routines in Yeoville.

At the more intimate level of housing, women were very keen to display their kitchen, their children and grand-children as well as the most comfortable and nice piece of furniture in their home. Men on the other hand tended to skip over their housing conditions, especially when they found them shameful, and would rather have their pictures taken in front of their building or on the street. But sometimes the proud display of a newly-owned bakkie was just as representative of home as that of the comfortable sofa shot by women in their interiors!

Stage 2: home away from home

In order to complement this vision of the neighbourhood as home, another workshop was dedicated to the notion of home-away-from-home, since most of our participants had arrived in Yeoville through complicated personal and geographical journeys. Participants were asked to bring or draw an object that reminded them of their home outside of Yeoville and were encouraged to describe and explain what this particular object meant for them.

Most of the participants, regardless of their age and gender, brought objects related to the place where they grew up as children and young adults and where their siblings, parents or more frequently their grand-parents still lived. It could be a wooden bowl carved by an older brother given as a gift, a treasure chest offered by a grandfather to his grandson, the house of grandparents in Bulawayo and the street corner where the participant would play football with a ball made of plastic bags... Whether of urban or rural origin, the importance of the filiation was always underlined, mothers and grandparents' advice and care often remembered fondly on this occasion.

It is thus not surprising that food, and the memory of food was also prominent: the gourmet memories of umbila (fresh, green mealies), of Ethiopian coffee, of inkobe (a Zimbabwean dish of pulse and grain). That this food could easily be found in Johannesburg and in particular in Yeoville which stores an incredible array of African food products is not really the point: it is the memory of the food, of its enjoyment as a child, and its connection to motherly and grandmotherly cooking that is missing for the participants, in this very city, today. The reference to food thus represents a nostalgic longing for a place as well as a past where, as a child, responsibilities and the need to eke out a living where less important, and the parents were close-by to provide for their children.

The importance of having roots (for participants stemming from rural Africa in particular) and the necessity of keeping in touch with them (through cooking techniques transmitted by Mom, through modern means of communicating with the family at home) were underlined by all the participants as crucial in their way to cope with living in Johannesburg. However, one can discern a strong sense of reconstruction in these recollections, clearly contrasting an idyllic life as a child in the village and the harsh conditions of life in Johannesburg and Yeoville in particular. This constrast probably works as a means of taking a distance from one's current life hardships more than they speak about the city itself: by remembering an often idealized and contrasted lifestyle to that of their life in Yeoville, some of our participants were able to express a more positive identity than that of poverty and migration.