Budget pressures erode capacity of the criminal justice system

- Arabo K. Ewinyu, Michael Sachs, and Olwethu Shedi

The criminal justice system faces severe challenges: as organised crime has risen, the capacity of the system has diminished. Here's what the numbers tell us

The criminal justice system faces severe challenges: as organised crime has risen, the capacity of the system has diminished. A close look at Budget expenditure shows that, in the past decade, the number of police officials has declined, as has police spending per citizen. This, while employee compensation has risen in the same period. Similar trends are evident in the courts. In correctional services, although the number of officials has remained stable, capital budgets are severely constrained. This shrinking resource base may well exacerbate the threat that crime and disorder pose to the economy and society.

Introduction[1]

A recent assessment of organised crime in South Africa painted a chilling picture of the rise of violent networks embedded in society and the state, which have become “an existential threat to South Africa’s democratic institutions, economy and people”.[2] The report suggests that the decline in police numbers in recent years has eroded police capacity and public trust. But while budget cuts have impacted on police capabilities, “the drastic decline in performance has far outstripped the falling number of personnel”. Failures of leadership, an absence of policy direction, widespread political patronage at all levels, and outright corruption and criminality have hollowed out the criminal justice system.

None of the problems in the sector can be overcome simply by allocating more resources through the budget. There is a direct relationship between the volume of inputs purchased by government (e.g. police hours worked, cars or equipment used) and the volume of outputs produced. We might define the outputs of the criminal justice system in various ways (e.g. police patrols, response times, crimes solved, criminals put behind bars etc). Improvements in productivity mean that output increases with the same or fewer inputs. More likely in South Africa’s case (as suggested in the Global Initiative report) is that productivity in the criminal justice system has fallen in recent years. In the budget, government has proposed a further fall in the value of inputs. Without countervailing improvements in productivity in the future, this will certainly reduce the outputs that the criminal justice sector produces.

In this article, we consider only the value of inputs allocated through the national budget. The most important of these resources are police employees and the work they do. As is the case for healthcare, education, and many other public services, labour is the most important input for policing, courts, and prisons, since these services “involve an essential human input” that cannot easily be substituted.[3] Employment levels and work effort are therefore a critical indicator of the value of inputs allocated to a policy goal. Ideally, the contribution of labour should be measured by estimates of hours worked. Here we report on a more rudimentary measure: people employed.

Police employment

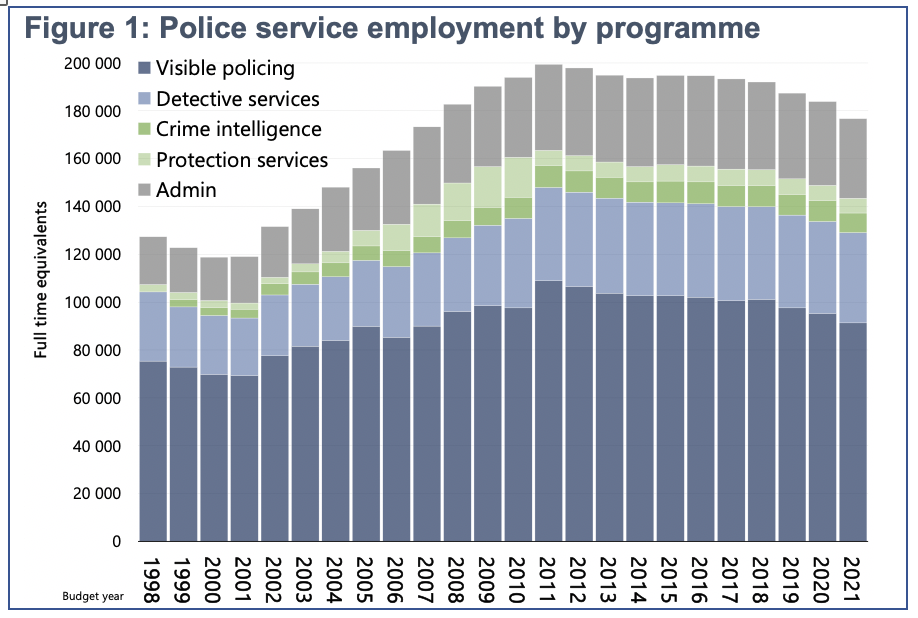

Figure 1 shows employment in the South African Police Service reported in national budget documents. Total employment in the service reached a peak of around 200 000 in 2012 and has declined since then. The visible policing programme accounts for about 52% of personnel, although this has fallen somewhat over the period because personnel have been reallocated to detective services and, to a lesser extent, administration. Crime intelligence accounts for about 5% of employees and has been stable over the period. This stability masks the erosion of expert capacity in crime intelligence detailed in the report of the Global Initiative.

VIP protection services grew substantially after 2004, reaching a peak of nearly 17 000 employees, or 9% of total police employment, in 2009. Employment in this programme was, however, strongly curtailed thereafter, and personnel appear to have been reallocated to visible policing. Protection services now account for about 3.5% of employment, numbering about 6 500 personnel. About 35 000 employees, or 19% of the total, work in administration.

Source: National Treasury (Estimates of National Expenditure, various years)

Employment by programme reported in Figure 1 does not tell us exactly what work employees do, only the programme under which they are employed. For instance, those working in the detective services programme are not all detectives, as the programme also employs administrative personnel. The payroll system gives a better indication of the balance between police officers and civilian personnel employed in the service.

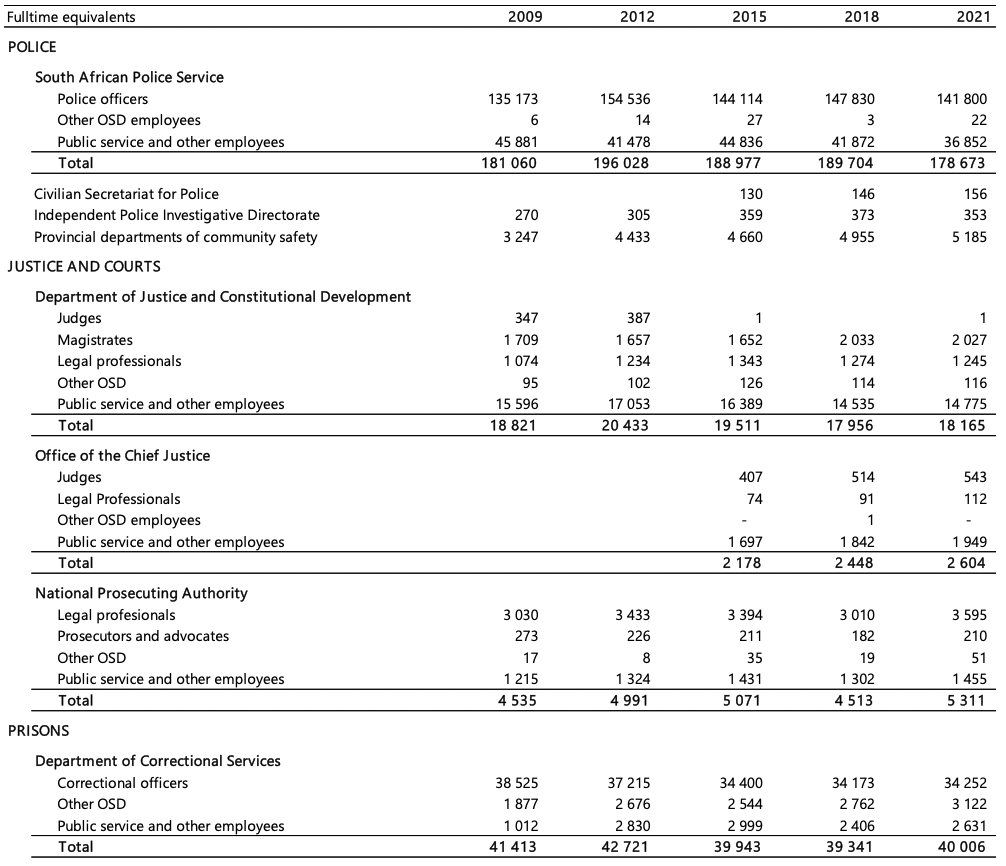

Table 1 shows employees on payroll who are designated by an ‘occupation specific dispensation’ or OSD, which indicates whether employees are professionals – such as police officers, magistrates or prosecutors. For the South African Police Service, the share of civilian personnel has fallen from 25% in 2009 to about 21% in 2021. In fact, the most recent years show an increase in the share of officers employed. Employment of civilians in provincial departments of community safety, however, does appear to have increased.

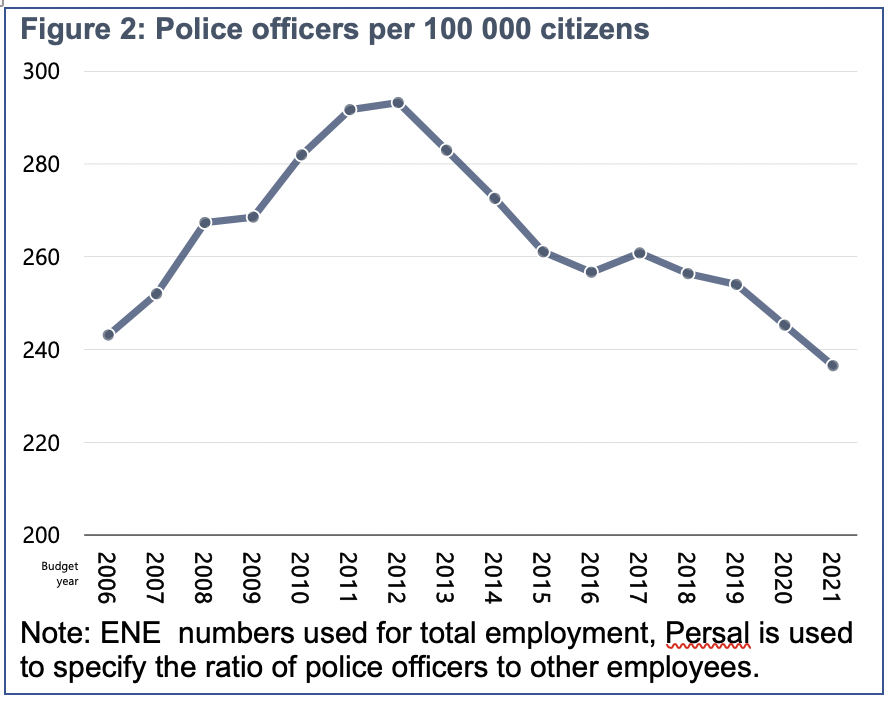

To place the impact of these trends in perspective, Figure 2 shows the number of police officers on government’s payroll relative to South Africa’s population. Ten years ago there were nearly 300 police officers for every 100 000 people. Today there are fewer than 240. Government’s current budget estimates imply that there will be further falls in police employment in the years ahead.

Source: National Treasury (ENE), Persal (GTAC-PEPA), StatsSA (Population Estimates)

Real police spending per citizen

A second gauge of resource allocation to the police service is presented in Figure 3, which shows real spending per capita. Our calculations attempt to capture three elements of the police budget: compensation of employees, transport costs (i.e. mainly police cars), and payments related to property (i.e. mainly police stations). The compensation budget is deflated using an average pay index, calculated from government payroll data. Transport costs are deflated with StatsSA estimates of inflation for private transport operators, while property payments are deflated with consumer indices of housing and utilities inflation. The rest of the budget is deflated using the headline CPI index.

Our analysis shows that by 2010, the year South Africa hosted the FIFA World Cup, the level of spending had increased to more than R2 000 per citizen (in 2020 prices). This increase in spending – largely reflecting increased employment of police officers – was well motivated. Concerns about crime, both as a social problem and a constraint to faster economic growth, were widespread at the time,[4] underscoring the need for better resources of the police as an essential component of South Africa’s development trajectory. But the increase in spending has now been almost completely reversed. By the time the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020, spending had fallen to below R1 700 per citizen, and if current budget plans are executed, police spending will fall even further in the years ahead, reaching its lowest point in the past 20 years.

Source data: National Treasury (ENE), StatsSA (CPI and price indices, and population estimates)

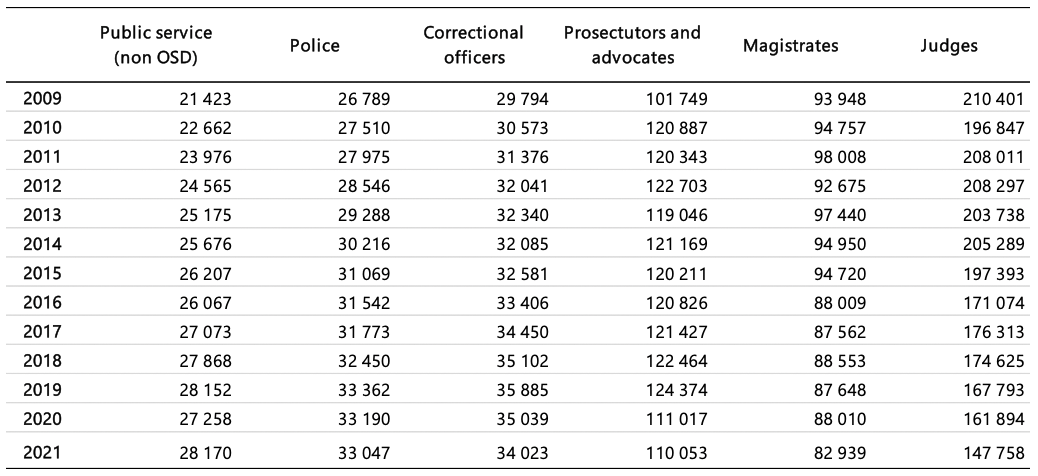

As in the case of healthcare and basic education, rising average pay has absorbed a large share of budget increases. Table 2 shows our calculations of average real earnings of employees in the criminal justice sector. Large increases in the earnings of police and other criminal justice professionals occurred between 2008 and 2010, when Occupational Specific Dispensations[5] were implemented. Since then, in addition to negotiated cost-of-living adjustments, government agreed to delink promotions from performance appraisal in the police system, adding significantly to budget pressure[6] while also weakening performance management (perhaps fatally). Police earnings have increased at about 2% faster than consumer inflation over the past decade (broadly in line with trends in the private sector), but budget allocations have not kept pace with pay increases agreed to by government. In effect, Cabinet has been deciding to increase pay while adopting budgets that effectively invalidate its own decisions. Compensation of employees has been contained within limits that forced down headcounts.

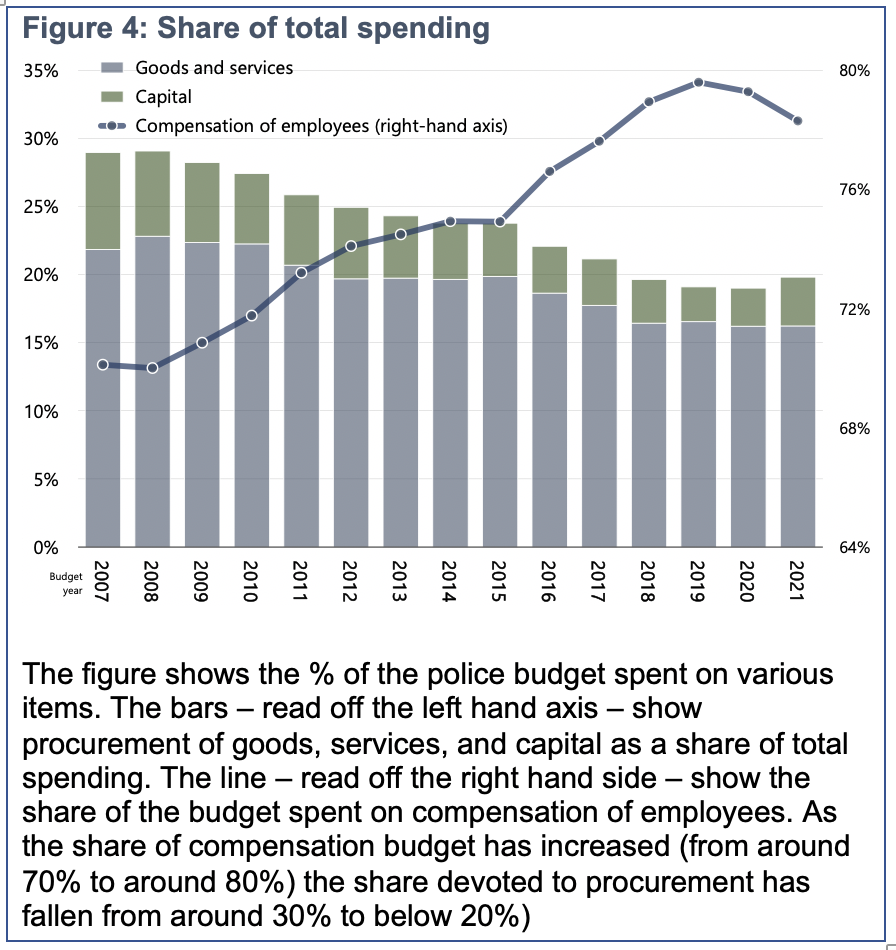

The combination of rising pay and constrained budgets has also led to a shift in the composition of spending over the last decade. As shown in Figure 4, spending on goods and services has fallen from 23% of total spending to just 16% in 2021. The share of spending on capital has also fallen (from 7% to 2.5% of spending). These shares have been pushed down as a greater share of resources are allocated to compensation, which increased from 70% of the budget in 2007 to nearly 80% today.

Source data: National Treasury (Estimates of National Expenditure, various years)

Remarkably, this crowding out of non-compensation spending has occurred even as the number of employees has fallen. This implies that the trade-off between rising pay and contained budgets has had a strong negative impact on the composition of spending. Even though there are fewer employees, they are operating in an environment of declining resources for critical complementary inputs. As we show below, similar shifts in the profile of spending are observable in the courts and justice system.

Justice, prosecutions, and the courts

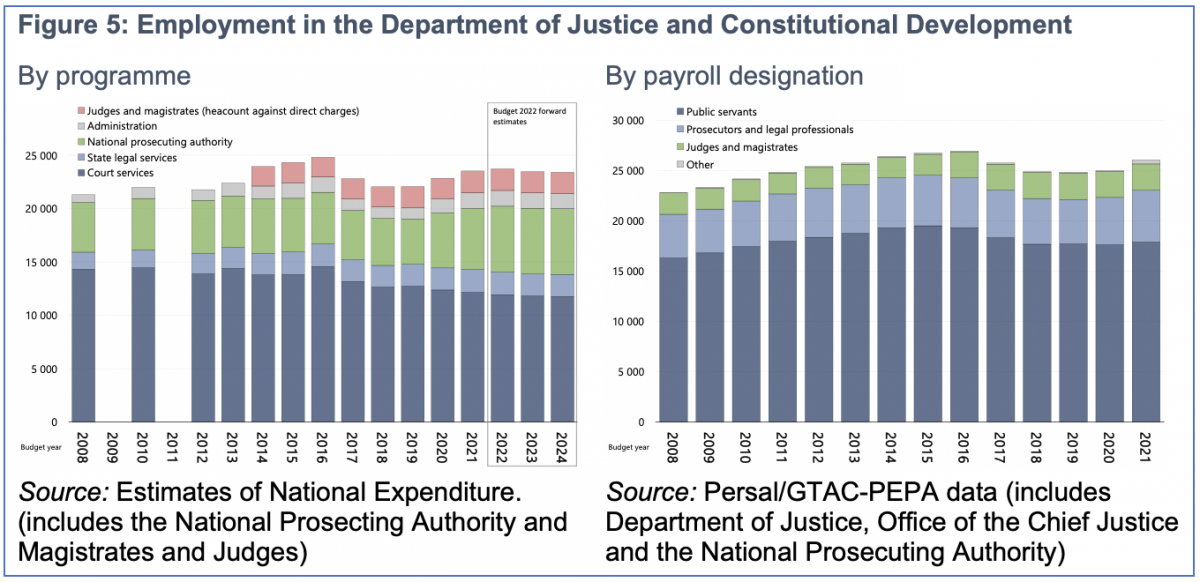

Employment levels have stagnated since 2016 in the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development (see Figure 5). The one area where employment has increased is for the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA). The NPA employed 4 400 personnel in 2018. Data from the Estimates of National Expenditure shows that this increased to 5 700 in 2021, with plans to add an additional 500 employees over the medium term. While undoubtedly welcome, this increase has been absorbed within the department’s budget, with the result that employment in court services has been reduced. Employees in the court services programme peaked at 14 500 in 2016 but this number has been reduced to around 12 000 personnel on current estimates.

Average earnings of employees in the courts and justice system (shown in Table 2) have followed the general trend of the public service, with one notable exception. Real pay for judges and magistrates has fallen significantly over the past decade. While police officers and lawyers benefit from the outcomes of collective bargaining, the salaries of judges and magistrates are recommended to the President by the Independent Commission on the Remuneration of Public Office Bearers, with the final decision requiring Parliamentary endorsement. The outcome has been strong pay improvements for those covered by collective bargaining, while the pay of those not so subject has been held down. While section 176(3) of the Constitution demands that “the salaries, allowances and benefits of judges may not be reduced”, it does not specifically prohibit the erosion of these gains through inflation.

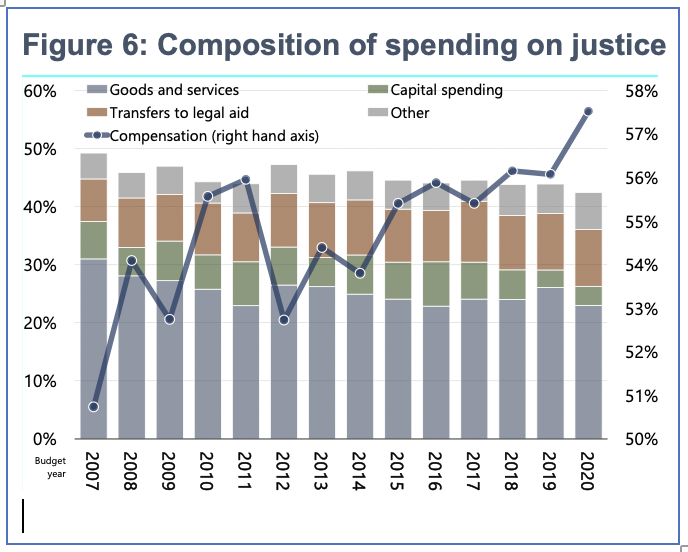

As is the case for the police, the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development has shifted its budget considerably to manage the rising pay of its employees, even while their total number has remained stable. Figure 6 shows that compensation spending now accounts for nearly 58% of the budget, up from 52% a decade ago. This has led to lower spending on goods and services and capital. Transfers to legal aid – the other major component of the department’s budget – appear to have maintained their share of expenditure, even though these budgets have not generally kept pace with need.

Source: National Treasury (ENE)

Correctional services

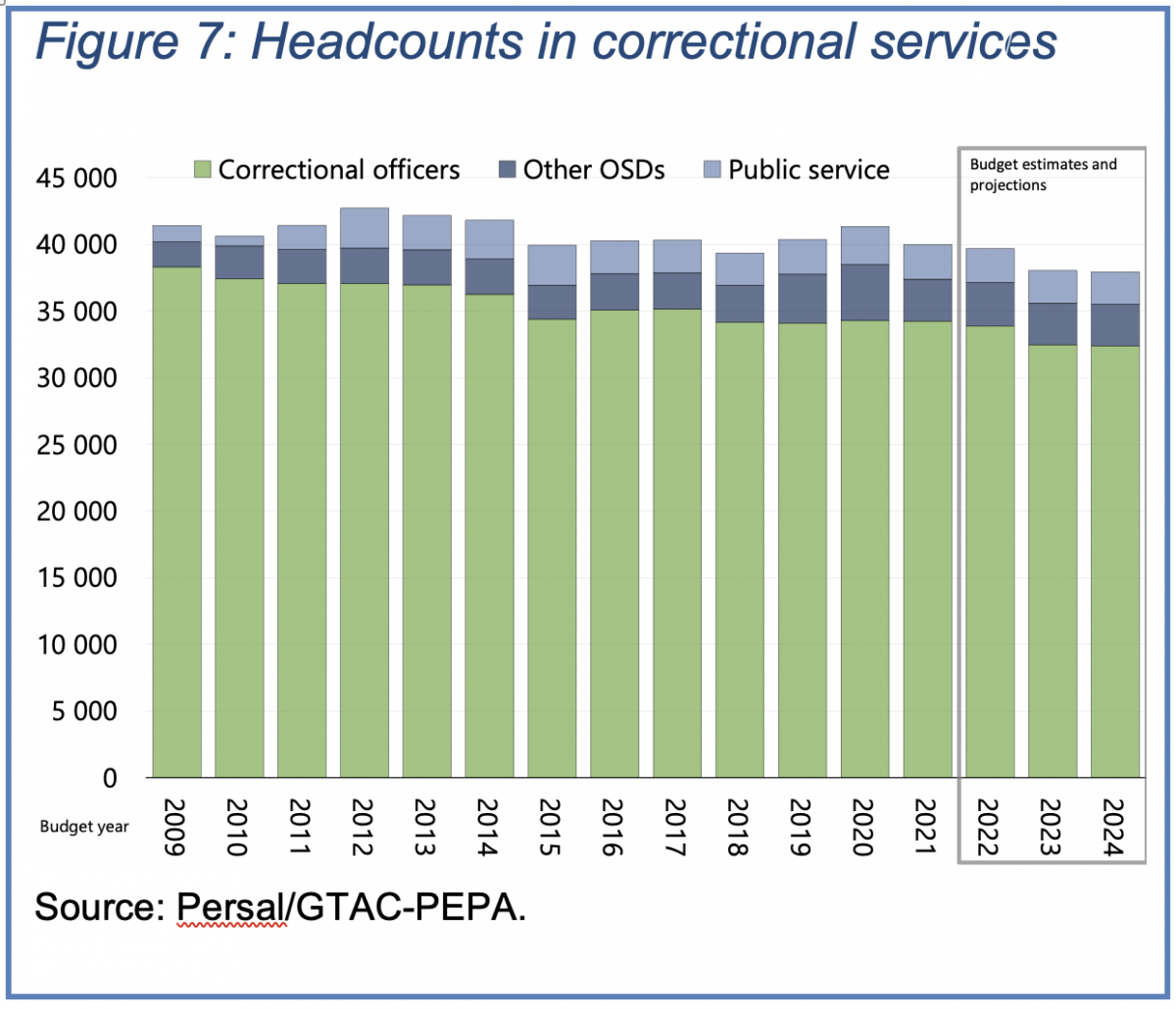

Staff numbers at the Department of Correctional Services have remained stable over the past decade, as shown in Figure 7. According to the payroll data, however, the number of correctional officers has fallen in this period, from about 38 000 officers in 2009 to 34 000 in 2021. This has been offset by the growth of other professional employees – mainly nurses, social workers, and educators – whose number has increased over the same period, with the share of public service employees remaining stable at around 6%.

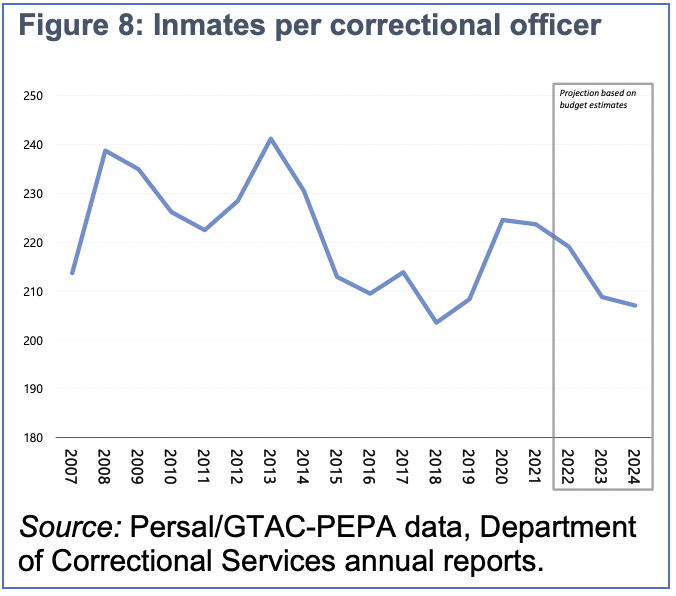

The overall stability in headcounts may well be justified in the case of correctional services, as the population of prisoners has also remained broadly stable over the same period. As a result, the number of correctional officers per incarcerated person has fallen over the past decade, but not dramatically, as shown in Figure 8. The 2022 budget estimated that the headcount would fall over the next three years by around 2 300 personnel, and this would lead to a reduction in correctional officers per prisoner.

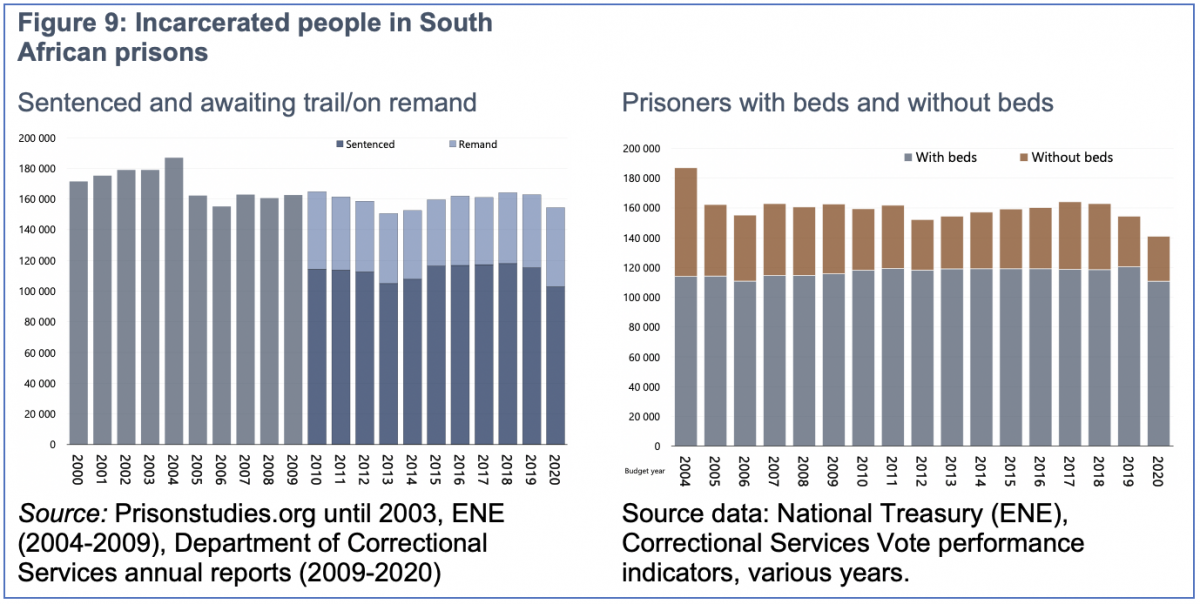

Despite the rising threat of organized crime and violence, the increase in prisoner numbers is constrained by the number of beds available in prisons. Around 40 000 people are incarcerated without beds according to the Treasury’s estimates of national expenditure, as shown in Figure 9, and the overall bed capacity within prisons has barely increased in recent years. Seen in this light, the binding resource constraint facing the prison system is not the ratio of employees to prisoners but the extent to which budgets allow for the building of additional prison facilities and the provision of these facilities with the appropriate number of personnel.

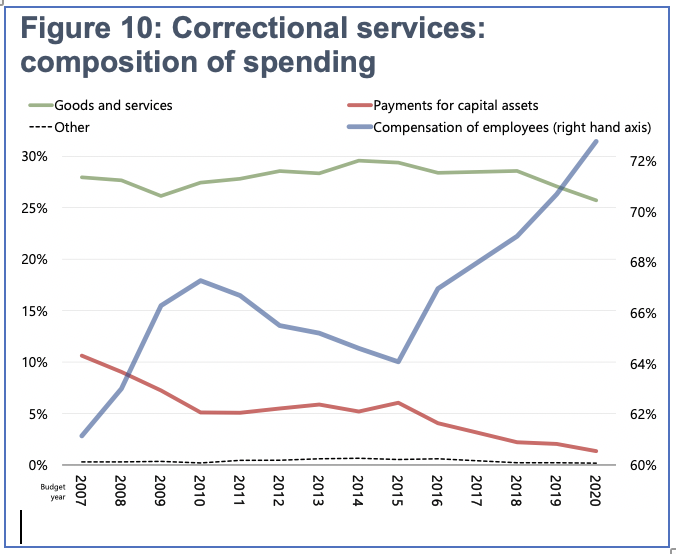

From this perspective, the role of the compensation budget in crowding out other essential expenditures is critically important. Figure 10 shows the composition of the department’s budget. Compensation spending increased from around 64% of the budget five years ago, to more than 72% in 2020. To accommodate this increase, capital spending has been pushed down to almost nothing. This means that budgets to build additional facilities are not available, and additional prisoners cannot be accommodated. The number of prison guards can remain stable with rising average pay. This resolution of the problem externalises the costs of fiscal consolidation onto society.

Source: National Treasury ENE

Conclusion

Binding resource constraints are one element of an overall crisis in South Africa’s criminal justice system. Since 2010, there has been a large fall in the number of police officers. Increased employment at the National Prosecuting Authority has come at the expense of falling employment in court administration. The prisoner population has remained static (despite increasing population and rates of crime) as capital budgets have been cut to accommodate rising pay for correctional officers. Added to this, magistrates and judges have seen their real pay substantially reduced over the last decade.

In his most recent budget speech, the Minister of Finance claimed that resources have been added to increase police numbers. However, next year’s budget assumes that police pay will fall significantly in real terms. As has been the practice over the past decade it is likely that additional resources will be needed to finance pay increases in line with, or above, inflation. In this more realistic scenario, current budgets imply that the police, (and indeed the whole criminal justice system) will continue down the path of falling headcounts and real budget cuts.

Resource constraints are by no means the only reason for the deep crisis in the system. But economic logic suggests that they have played an important role. If current budgets are executed as tabled, further falls in personnel numbers are likely to combine with even greater pressure to curtail non-personnel budgets. The resource base of the criminal justice system will continue to decline, and the ability of government to rebuild the system will be undermined as low morale, insufficient budgets for essential goods and capital spending, and falling headcounts conspire to worsen outcomes.

Table 1: Government employment in the criminal justice sector

Source data: Persal (GTAC-PEPA)

Table 2: Monthly average gross earnings of criminal justice employees (2020 prices)

Source data: Persal (GTAC-PEPA), StatsSA (CPI index)

References

Atkinson (2005) Atkinson Review: Final Report: Measurement of government output and productivity for the National Accounts

Stone, Christopher. 2006. ‘Crime, Justice, and Growth in South Africa: Toward a Plausible Contribution from Criminal Justice to Economic Growth’. SSRN Electronic Journal. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.902387.

Global initiative against transnational organised crime. 2022. Strategic organized crime risk assessment: South Africa.

ISS. Institute for Security Studies. 2021. Briefing Note: South African Police Service Resourcing and Performance 2012 to 2020. 14 July 2021

[1] This article is largely drawn from our report: Public Services, Government Employment and the Budget (https://www.wits.ac.za/media/wits-university/faculties-and-schools/commerce-law-and-management/research-entities/scis/documents/PEP-public-services-and-employment-report-2022.pdf), which covers basic education and healthcare, and also provides details of data sources and methods.

[2] Global Initiative, 2022

[3] Atkinson, 2005

[4] See for instance, Stone, 2006

[5] Occupation Specific Dispensations (OSDs) were agreed in collective bargaining in 2007 and implemented over the next few years. Each OSD came with a unique revised salary structure for each of the identified occupations in the public service. Large above inflation cost-of-living adjustments were implemented simultaneously with the revised salary structure, resulting in a large increase in government pay between 2008 and 2010.

[6] ISS, 2021

*This article first appeared in Econ3X3

*Arabo K. Ewinyu is a Research Manager at the Southern Centre for Inequality Studies, Michael Sachs is an Adjunct Professor at Wits University and Olwethu Shedi is an Associate Researcher at the University of Johannesburg.