Wits Researchers Call for Data-Driven Action on Climate Change as a Public Health Emergency

- FHS Communications

Wits researchers took centre stage at the Enhancing Belmont Research Action (ENBEL) 2025 Conference, contributing to the global conversation on the impact of climate change on child health. They tackled one of the most pressing challenges in public health: how to accurately measure the health impacts of anthropogenic climate change—and use that evidence to shape policy, guide investment, and drive global action.

Wits researchers took centre stage at the Enhancing Belmont Research Action (ENBEL) 2025 Conference, contributing to the global conversation on the impact of climate change on child health. They tackled one of the most pressing challenges in public health: how to accurately measure the health impacts of anthropogenic climate change—and use that evidence to shape policy, guide investment, and drive global action.

Organised by the Global Heat Attribution Project (GHAP), the special panel session, titled “Disambiguating Attribution: Are We Speaking the Same Language?” brought together leading voices in climate-health research, including Professor Matthew Chersich, Research Professor and Executive Director, Wits Planetary Health Research (Wits PHR) , Dr Nicholas Brink, and Dr Danielle Travill, both clinical researcher at Wits PHR, a division of Wits Infectious Diseases and Oncology Research Institute (IDORI). They are working on the GHAP project, and they showcased Wits’ growing leadership in climate-health research, highlighting maternal and newbornoutcomes in regions most vulnerable to climate shocks.

‘Attribution’ in climate and health research refers to statistical analyses that isolate what proportion of a poor health outcome can be attributed to anthropogenic climate change (as opposed to natural climate variation and other causes). This calculation builds on analyses of how the probability or intensity of a specific climate event, such as a flood or heatwave, was increased by anthropogenic climate change.

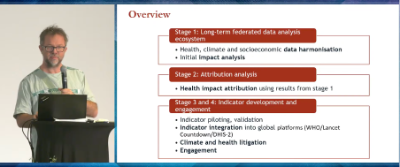

Caption: Professor Matthew Chersich presenting on the statistical analysis steps used to calculate the climate impact attribution

Prof Chersich, who is also a Research Fellow in Public Health and Primary Care at Trinity College Dublin’s School of Medicine, highlighted the project’s goal to develop practical tools that can drive real-world action. “I think the exciting part of this project is you try and then use these attribution analyses to really make a practical difference to the field,” he said, adding that understanding how many cases of preterm birth in a country or district come from climate change contextualises its consequences.

Central to this effort is GHAP’s development of a global federated data system, which integrates birth outcomes, climate data, and socioeconomic indicators from as many as 20 countries. Once harmonised, these datasets will allow researchers to conduct attribution analyses that quantify how much of a health burden—such as preterm birth—can be directly linked to climate change-related drivers, such as extreme heat. “You isolate which part of that is attributable to climate; that then is separated into burden of disease from natural variation as opposed to human-caused climate change,” he explained.

He points to the findings as a critical link in the causal chain between climate change and health impacts, which has relevance for both scientific and public audiences. He says governments and decision-makers can use this information to allocate resources more effectively, design targeted interventions, and, where necessary, hold contributors to climate change emissions accountable through legal processes. “If we can separate the proportion of preterm births attributable to specific sources—from fossil fuel projects to national emissions—then we can demonstrate responsibility in a measurable way,” he noted.

Dr Travill reflected on the challenges of working across fields such as epidemiology, law, and climate science. She recalled that, in an early GHAP workshop, researchers from different disciplines all used the term “attribution”, but with different underlying meanings—an eye-opening moment that underscored the need for shared definitions. “Speaking the same language is incredibly important, particularly when you’re trying to move forward and advocate for change at such a large scale ,” she said.

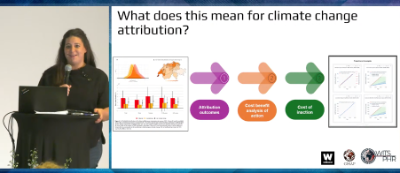

Caption: Dr Danielle Travill unpacking the concept of climate change attribution

Her presentation showed how the concept of attribution has long been used in epidemiology to quantify how much of a disease can be prevented by removing a specific exposure. These methods, she explained, played a decisive role in landmark public health breakthroughs and advocates for interventions to address health harms for example between smoking and lung cancer, or proving that up to 70% of cervical cancer cases could be prevented by preventing infection with human papillomavirus (HPV).

Applying these same methods to climate change, Travill highlighted that attribution can help quantify not only health outcomes but also the economic impact of carbon emissions. This includes the cost of additional healthcare, infrastructure strain, and broader productivity losses. This type of evidence can guide strategic decision-making, ensuring that limited resources are directed where they can make the greatest difference.

Dr Travill also noted that while climate-health attribution research is expanding, most detailed studies originate from high-income settings. With many low- and middle-income countries facing the worst climate impacts, this bias presents a significant barrier to action. Through the GHAP project, African and other developing countries can contribute their own quality-controlled data to global research outputs.

In policy efforts, attribution analyses can also be used to calculate years of life lost, disability-adjusted life years, and the associated costs, “which allows us to better evaluate adaptation and mitigation interventions in terms of health outcomes and their costs,” explains Travill.

Both speakers stressed that climate change must be recognised as a public health emergency—not merely an environmental or economic concern. Drawing on lessons from past public health successes, they argued that robust data, combined with policy engagement, advocacy, and public interest litigation, offer the most effective path to reducing harm and safeguarding vulnerable populations.

As GHAP progresses, its findings are expected to guide the development of the world’s first standardised indicator to measure the proportion of preterm births attributable to climate change. If adopted by the World Health Organization and other international mechanisms, it could reshape how countries measure progress on climate action, maternal health, and sustainable development.

Watch the recorded panel discussion here

Funding and Programme Acknowledgement

The Global Heat Attribution Project (GHAP) is part of the Wellcome Trust's Attriverse programme, which focuses on creating digital tools for understanding health impacts. It is supported by Wellcome Trust grant [309105/Z/24/Z].