Geological adventures in Greenland

-

Greenland is a geological paradise, if you’re tough enough to take it on. Tough as in carrying a 35kg rucksack for 10 hours a day, fishing for your supper and sharing a tent with your colleague for four months.

Sixty years ago, one tough Witsie geoscientist jumped at the opportunity to do that, and now his groundwork is translating into mining development on that chilly continent.

As an undergraduate at Wits from 1952 to 1955, John Ferguson (BSc 1956, PhD 1967, DSc 1975) was exposed to some of the great geological wonders of the world. The enormous Witwatersrand Basin, the biggest single depository of gold plus uranium in the world, is, in part, exposed on the campus. Fifty kilometres away is the Vredefort Circular Structure, and about 40km to the north of campus is the unique Bushveld Complex, the largest layered igneous complex in the world.

These features ignited John’s interest in similar bodies elsewhere in the world.

When he had completed an MSc at McGill, Montreal in 1958, his Scandinavian professor-supervisor invited him to join the newly created Greenland Geological Survey. The adventure was on!

Greenland

Far from being just a permanent icecap covering a continent, Greenland has a rocky fringe along the shorelines up to 200km wide, as well as rock nunataks poking through the icecap. The rocks exposed cover the entire geological record and an area the size of Norway; the oldest are about 3800-million years old and the newest are recent volcanics.

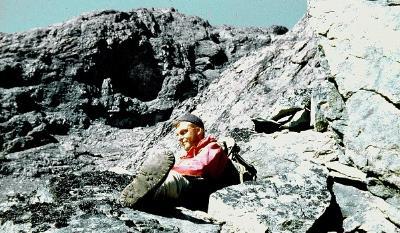

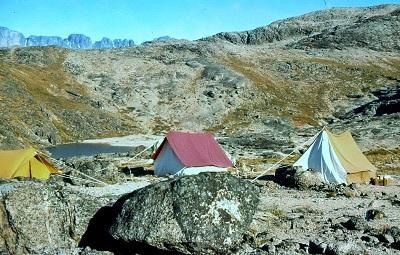

Geological parties exploring this inhospitable landscape had to get around by boat or by helicopter. Their camp consisted of three two-man tents used for sleeping, cooking and storage for a stay of three or four months. Although there were two small villages and a minor airport within 50km, they were isolated by fjords and unreachable on foot. There was no telecommunication contact. In the first season the field teams were not equipped with a firearm but a nearby party had a close encounter with a polar bear, so they were then issued with revolvers.

Field party members carried a pack containing rock samples and food for the day as well as a fishing rod. Fish and blueberries were the only fresh food available; luckily, cod and salmon were plentiful.

Unfortunately John was involved in a helicopter crash in his first field season and spent 1½ years getting ‘patched up’ before returning to Greenland.

Since those days, he has explored Southern Africa, Canada, Chile, Mexico, Mongolia, China and Australia for diamonds, gold, platinum group elements, base metals, coal, uranium, and heavy mineral sands. He has been a Reader-Professor at Wits, Chief Scientist at the Bureau of Mineral Resources, Geology and Geophysics in Canberra, and an NRC Fellow at the Canadian Geological Survey.

Circular structures

From late 1958 to 1974, John was back in South Africa, on the Wits staff. He and Louis Nicolaysen, Professor of Geophysics at the Bernard Price Institute, shared an interest in shock-metamorphosed circular structures and became lifelong friends. In addition to working on the Vredefort Structure they investigated circular structures in Namibia, and John went on to visit sites in Canada and Australia.

After 25 years of research, he and Louis presented a paper in which they suggested that a large percentage of ‘meteorite impact’ sites were in fact produced by volcanic detonation derived from fluid-loaded magmas generated within the earth’s mantle. This interpretation – based on the fact that the sites are not distributed randomly, as meteorite impacts should be – was not always well received but has recently had a more positive response. This resulted from a 2013 paper authored by John where he revisited the topic, using more examples.

Australia

On leaving Wits in 1974 John emigrated to Australia and joined the Federal Geological Survey (Bureau of Mineral Resources, or BMR, now Geoscience Australia). Having worked during vacations at the Virginia Gold Mine as an undergraduate and also calculating the ore resources at Blind River, a Witwatersrand lookalike in Ontario, he could claim some knowledge of uranium, which was also recovered from the gold-rich reefs. As a result, he was assigned to study new uranium discoveries in the Pine Creek Geosyncline, Northern Territory, and got involved with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as the Australian representative to various working groups. He was on the organising committee of an IAEA International Uranium Conference in Sydney and co-edited its proceedings.

His South African exposure to kimberlites, diamonds and craters also allowed him to pursue research on these topics.

By joining the BMR, and with a Fellowship at the Australian National University, John had access to the most advanced analytical instrumentation in the world for the study of minerals and rocks. He was also among a group of up to 350 knowledgeable geologists. In 1982 he was promoted to Chief Scientist and Head of the Division of Petrology and Geochemistry. He also served as Acting Director for a short period.

Corporate world

When John left the BMR in 1985, he decided to try his hand at being a director-geologist of small, publicly listed mineral exploration companies. This came full circle back to Greenland, where most of the exploration was focused.

The country has a small population of only 57 000, and mining exploration is encouraged. Technical help from Denmark is available, the jurisdiction is stable and the relevant infrastructure is in place.

John explains what’s at stake:

“Exploration activity in Greenland and the acquisition of several mineral tenements resulted in a brown-fields discovery of a major iron ore resource high in titanium and vanadium. Metallurgical studies are now being addressed. A further large tenement was secured over an area where earlier survey studies had identified a large intrusive body high in rare earths and niobium which was then subjected to extensive drilling defining a good resource. Discussions are now being held with potential interested parties to exploit the resource(s). Given that China is the largest rare earth producer and is threatening to block supplies to the USA, this deposit now takes on extra significance. Within this tenement there is also a large resource of alumina-rich rocks which are suitable for a feedstock for aluminium, fibre-glass, special cement and filler; production has just started. In NW Greenland, a reported minor heavy mineral resource was re-investigated by undertaking a drilling and sampling programme resulting in the definition of a major ilmenite resource. Mining will commence in 2020.”

Little wonder that the government of Greenland named John “Greenland Prospector and Developer of the Year for 2011”.

Back in Australia, his Bushveld knowledge was put to use in identifying a reef rich in platinum and gold. Fittingly, it’s now called the Ferguson Reef and awaits development. A small team also identified a grassroots coal exploration site which is now the Jellinbah East Mine, Queensland.

A Life Fellow of the Geological Society of South Africa, John now lives in the foothills of Australia’s Snowy Mountains. He is an avid bird watcher and has so far identified 164 bird species on his bush property.