Finding alternatives to our favourite dirty words

- Shaun Smillie

An energy crisis built on an obsession with fossil fuels. Can alternative energy resources save the day for South Africa?

For a long time in South Africa’s energy sector, coal was king, responsible for heavy lifting the country into the industrial age with its offering of cheap, reliable and abundant energy.

But in a post-industrial world, coal has become the black sheep, as cheaper and greener energy sources are becoming available.

South Africa still has a long way to go before it is weaned off coal fully as the main source of energy, if the state has its way, but private enterprise and the forces of economics might have the final say in the way that we generate energy in the near future.

That despicable, dark “L” word

In mid-October, while the country was in the grips of a week of loadshedding, the government released its Integrated Resource Plan (IRP2019). The plan mapped out what South Africa’s energy generation mix would be for 2030.

Coal will still play a major role in South Africa’s energy future, contributing 58% of South Africa’s energy needs.

The balance of 20.4 gigawatts worth of electricity will come from renewable energy sources in the form of wind, solar, and hydroelectric power, with wind contributing 18% of the country’s electricity.

The problem with coal headlining the IRP2019 plan, says Bob Scholes, Professor in Systems Ecology at the Global Change Institute at Wits, is that it is no longer cost effective.

“People keep on going on about South Africa having a world class coal resource, but it is no longer true. We have picked out the juicy bits and from here on out, our coal resource is of low quality or very difficult to extract,” he explains.

“We have a much more world-class solar resource. Actually, new coal build is coming out twice as expensive as new solar or wind. So why choose a technology that is twice as expensive?”

Scholes adds that today whole countries are being run on renewables.

“It was always thought to be impossible. But now the battery technologies and smart grid technologies are so good you can essentially run any economy in the world entirely off renewables.”

That ugly “F” word

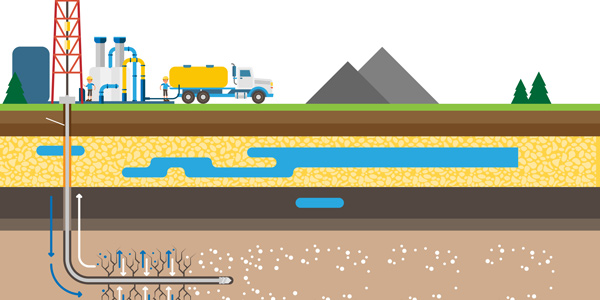

What is not in this energy mix proposed by government is something that, a few years ago, promised to be a saviour of the country’s economy. The highly emotive debate on hydraulic fracturing of gas shales, or fracking, has since died a quiet death.

Fracking changed the energy landscape of the US. Over the last decade the US has increased its oil production, and in 2012 it overtook Russia as the leading gas producer, all thanks to fracking. In South Africa, the Karoo was speculated to contain shale gas reserves of hundreds of trillions of cubic feet. Talk of fracking in the Karoo ignited a heated debate on whether this should be allowed in this fragile environment.

Scholes co-led the strategic environmental assessment of shale gas development for the Department of Environmental Affairs. They discovered that developing the Karoo shale gas resource was not economically viable when considering today’s energy prices. The main reason for this is the geological make-up of the Karoo.

“The fundamental reason is that horizontal drilling works just fine in the shale gas beds of the United States. They are horizontal beds of great extent,” says Scholes.

“The problem in South Africa is that we can’t drill for several kilometres horizontally, because you bump into a dolerite dyke. The distance we can go horizontally is not enough to make it economically viable, given the characteristics of the gas present.”

There are more conventional gas reserves available in South Africa. Included in this is the newly discovered Brulpadda field located 175km off Mossel Bay. It holds promise, but is not the sole solution to our energy challenges, says Scholes.

“That is a resource of significant size, equivalent to two years of South African energy use. It is substantial, but not manna from heaven.”

As the government is searching for solutions to the country’s energy problems, the private sector is already taking advantage of new green technologies, as it looks for a more reliable and cheaper alternative to Eskom. Home owners, for example, are taking advantage of increasingly cheaper solar panels and are moving off the grid.

That dirty “C” word – cleaned up

But the private sector can benefit further from alternative technologies that would make them independent of large utilities such as Eskom. Professor Thokozani Majozi in the Wits School of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering and his team are advising industry on using waste heat to power electrical needs. Industries such as petrochemicals, food and beverage, pulp and paper, and the chemical sector all have waste steam at their disposal that could be run through a turbine to generate electricity. This steam is usually generated by coal.

“Coal is here to stay, but we need to think differently about how we use it,” says Majozi.

The poster child of generating steam for electricity is petrochemicals giant Sasol.

“A company like Sasol generates one gigawatt on site and the other gigawatt it will get from the grid,” explains Majozi. If Sasol had to source both gigawatts, it would mean the company would be drawing nearly 5% of the power available on the national grid.

“If you are saving one gigawatt, that is equivalent to about 10 000 houses in a big suburb,” says Majozi. “It is a major impact.”

The “B” word to save the day?

Biofuels are another alternative source being used effectively in countries like Brazil.

Biofuels are produced from living matter. South Africa has a lot of waste material that lends itself to use as biofuels.

The problem with biofuels, however, is that there is still so much to be learnt about them, and how energy from biofuels can be made more efficient, says Michael Daramola an Associate Professor in Wits’ School of Chemical and Metallurgical Engineering.

Daramola and his students are working on converting animal fat into biodiesel, using a catalyst developed from another South African waste material – animal fat.

“The animal fat from the slaughter slabs end up in landfills. It decays in the landfills and causes a lot of environmental problems,” says Daramola.

However, biodiesel is often difficult to use in colder environments because of poor flow performance. To solve this problem, additives have to be added, which, due to a lack of research in this field, often comes up to guess work, says post-doctoral fellow, Dr Cara Slabbert.

Together with Professor Andreas Lemmerer in Wits’ School of Chemistry, Slabbert has been working on improving the qualities of biodiesel.

The duo discovered that by shortening the carbon chains of fatty acid methyl esters, they could reduce the melting point of biodiesel significantly, making the fuel much more user-friendly.

“The next step I would think is to try it. We would need to find out if it is viable for use in a vehicle,” says Slabbert.

How about the “H” bomb?

Whatever the future of South Africa’s energy mix in the next 10 years, Scholes sees no place for fossil fuels like coal.

“We will have to replace our generation capacity in approximately the next decade. Why will we replace it with more of the same?”

There are other renewable power sources on the horizon, which if tapped properly, will provide huge energy resources for not only South Africa, but for the rest of Africa.

Near the port of Matadi in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a sharp bend in the mighty Congo river squeezes the river into a gorge that is just 250m wide.

This is the site of the grand Inga dam, which could in future be the largest hydroelectric project in the world.

“The Congo river could produce more energy than we could ever use,” says Scholes. “But the problem is how do we get it from there to here and the main constrain on that is not an engineering one, it is a political security constraint.”

- Shaun Smillie a freelance journalist.

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the ninth issue, themed: #ClimateEmergency how our researchers investigate the impact and implications of global change and climate change on people, places, and politics.