More gorilla than chimp

- Wits University

Surprising results from a new study reveal the heel bone from our fossil relative is closer related to gorillas.

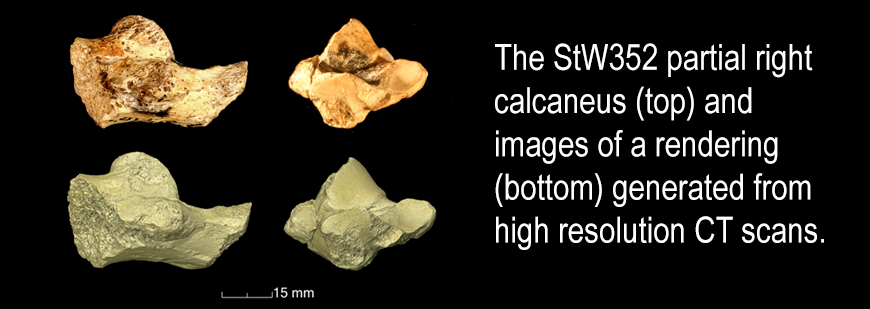

The new study that for the first time examined the internal anatomy of a fossil human relative’s heel bone, or calcaneus, shows greater similarities with gorillas than chimpanzees.

The study, titled: Trabecular architecture in the StW 352 fossil hominin calcaneus and published in the Journal of Human Evolution, was undertaken by a team of international researchers from the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, Duke University, University of Southern California and Indiana University in the US.

The team examined the internal anatomy of our human relative, the StW 352 Australopithecus africanus fossil, from South Africa’s rich fossil record in the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site, some 40km from Johannesburg.

They analyzed the structure and orientation of trabecular struts – the spongy material inside a bone – in the fossil from Sterkfontein Member 4, demonstrating greater similarities between it and the heel bone of gorillas rather than humans or chimpanzees.

In doing this, the team revealed new insights into how our ancestors moved through and interacted with their environment approximately 2 – 2.5 million years ago. Similarities between the fossil from Sterkfontein and gorillas indicate that Australopithecus africanus, the species of human ancestor (or hominin) also represented by the Taung Child, or at least this individual member of the species, exhibited gorilla-like levels of joint mobility and structural reinforcement.

Results of the new study were surprising because other recent studies of the australopithecine calcaneus, focusing on its external anatomy, have emphasised similarities with chimpanzees or humans.

However, since the organisation of trabecular bone is determined in part by how an animal interacts with its environment during its lifetime, the gorilla-like features observed in the present study are particularly compelling in revising how we view behavioural reconstructions of our australopithecine ancestors.

Lowland gorillas are generally regarded as less arboreal than chimpanzees – they spend less time in trees and generally less time climbing – although it is important to remember that even gorillas depend on arboreal resources for their survival. Humans are the only truly terrestrial primate still alive today. Thus, the gorilla-like features in the Australopithecus africanus calcaneus substantiate claims that our hominin ancestors depended on arboreal resources for their survival, but importantly, it provides evidence that gorilla-like foot function should be considered more frequently when discussing the evolution of human feet and how they functioned within the environment.

Ultimately, whether internal structure of the Australopithecus africanus calcaneus from Sterkfontein indicates gorilla-like levels of arboreal resource exploitation, or whether it reveals greater variability (mobility) in foot interactions with uneven terrain compared to those characterising modern human feet, awaits follow-up research that the investigators are currently undertaking.

Wits University researchers:

Dr Bernhard Zipfel is a palaeoanthroplogist with a special interest in the biomechanics and evolution of the human foot, the origins of hominin bipedalism, palaeopathology and the preservation of natural history collections. He became the University Curator of Fossil and Rock Collections at Wits in 2007 and was formerly Head of the Department of Podiatry at the University of Johannesburg (1990-2006). He curates all fossil collections housed at the Evolutionary Studies Institute at Wits. He holds qualifications in Podiatric Medicine and Post-School Education from the University of Johannesburg, a B.Sc. (Hons) from the University of Brighton and a PhD from Wits. He is the past President of the Palaeontological Society of Southern Africa (2012 to 2014).

Professor Kristian Carlson is a Reader in the Evolutionary Studies Institute at Wits. He has research interests in documenting and understanding form and function relationships in the musculoskeletal system (functional morphology), focusing in particular on living and extinct primates. He emphasises understanding these relationships in living organisms through careful comparative and experimental research in order to reconstruct analogous relationships in extinct organisms, such as human ancestors. These behavioural reconstructions are crucial elements for understanding the palaeobiology of extinct taxa, particularly in shedding light on how they interacted with their habitat.

US researchers:

Dr Angel Zeininger (lead author of the paper) is a Senior Lecturing Fellow and co-director of the Animal Locomotion Lab in the Department of Evolutionary Anthropology at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. She studies the development of walking in humans and nonhuman primates, with an emphasis on how hand and foot postures change throughout ontogeny. Her research directly tests structure-function relationships of hand and foot bones by combining experimental biomechanics with 3D analyses of internal trabecular bone architecture, first in living primates, and then in extinct fossil human ancestors to inform reconstructions of locomotor behavior and the evolution of bipedalism.

Dr Biren Patel is an Associate Professor at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. With interests in anatomy, biomechanics and biological anthropology, he studies the functional morphology of hands and feet in order to better understand the evolution of different locomotor behaviors in human and non-human primates.