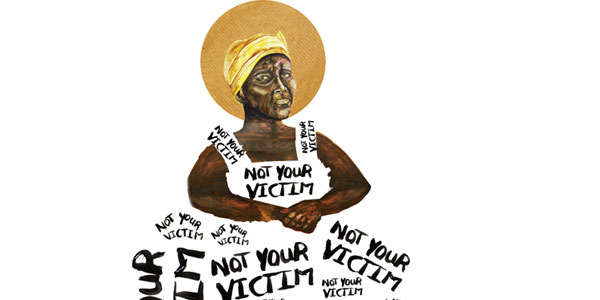

We’re not your victims

-

COLUMN: Srila Roy says that feminists in the Global South are fighting the battle on two fronts, making a history of their own.

Countries in the Global South have long robust histories of feminist resistance and agency, not least in moments of national liberation and decolonisation. And yet, these locales are more commonly known for staggering and endemic rates of gender-based violence (GBV).

There is a pervasive tendency – among policymakers, the media and even academics and researchers – to ignore the agency of women and cast them, instead, as helpless victims of backward and ‘primitive’ cultures and societies.

The Global South even provides the targets of and the moral reasons for specific kinds of humanitarian intervention. Think for instance of the ways in which international NGOs focus on ‘saving’ women and children in countries like SA. Many are even led by women who identify as feminist. In other words, the Global South has served less as a site of feminist struggle in its own right than with the making of feminist subjects elsewhere.

Considerable energy has gone into debunking these assumptions — that feminism originates in the West and spreads to the rest of the world, and that the non-West is, in turn, populated by victims who enable white, Western women to pose as saviours.

Battle on two fronts

We now have stories of being a feminist in very many places in the world, in struggle with very many patriarchies. What is perhaps unique to feminists in ‘our’ parts of the world is that we have to struggle on at least two fronts: we have to speak back to local patriarchs who tend to dismiss our struggles as derived from Western ones and secondly, we have to disrupt the hierarchies and assumptions of white Western feminisms.

We have to constantly stress that we too are making history, to establish ourselves as subjects worthy of national citizenship and belonging, on the one hand, and as agents, on the other. And yet, the loudest feminist voices continue to belong to white feminists in the North.

Part of the problem of the continuing dominance of Western feminism is not only the exclusion of other feminist voices and histories, but also their inevitable flattening into one singular and homogenous mass. So, when ‘we’ in the Global South speak, it is as if we speak in one voice, thereby erasing the considerable differences and even inequalities that exist within ‘our’ feminisms.

Taking the lead

In recent years, we have not only seen the expansion of gender and sexual rights struggles in countries like India and SA, but we have also witnessed a more intersectional turn. For instance, in India, Muslim women emerged central to the nationwide protests against the right-wing Hindu nationalist government which took place at the end of 2019. In SA, women – black and queer – expanded the remit of the “Fallist” student movements of 2015-16, beyond the issue of higher education alone, by making sexism, sexual violence and heteropatriarchy central to a decolonial agenda.

I lead a project called Governing Intimacies – located in the School of Social Sciences (with support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation) – which is precisely trying to map some of the complexities of feminist struggles in the Global South. By specifically placing southern Africa in conversation with India, the project has been able to reveal the surprising resonances and dissonances in our contexts.

As part of the project, I have co-edited a volume of essays on the MeToo movement in India and SA as a way of thinking more intersectionally, comparatively and transnationally about questions of GBV and cultures of resistance. Such a lens undercuts the hegemony of the North while offering a different way forward, from a genuine feminist theorising of and from the south. This book, then, is also part of the project’s wider goal to build theory in the south on the south, which is feminist in orientation and spirit. It contributes to shaping future research and teaching, but also builds public memory of feminist resistance and reinvigorates our commitments to gender just futures.

- Srila Roy is Associate Professor of Sociology and Head of Development Studies at Wits. She wrote Remembering Revolution: Gender, Violence and Subjectivity in India’s Naxalbari Movement, is editor of New South Asian Feminisms and co-edited New Subaltern Politics: Reconceptualising Hegemony and Resistance in Contemporary India. Her book on feminist and queer politics in India is scheduled for publication in 2022. Roy is the 2022 Hunt-Simes Visiting Chair of Sexuality Studies at the University of Sydney, Australia, and was awarded a Rockefeller Foundation residency in Bellagio, Italy.

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the 13th issue, themed: #Gender. We feature research across disciplines that relates to gender, feminism, masculinity, sex, sexual identity and sexual health.