Virus wages war on women

- Erna van Wyk

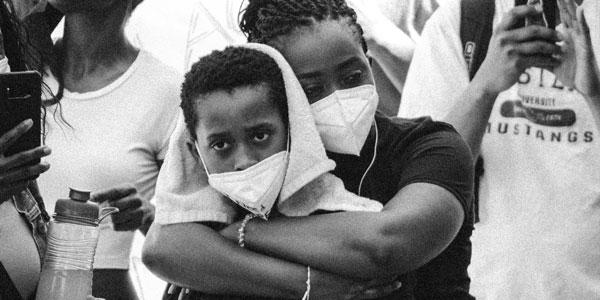

Almost everyone has suffered in some way from the effects of the Covid pandemic – but women have suffered far more.

During pandemics, women are hit hardest and are disproportionately affected in the health, socio-political and economic arenas. The Covid-19 outbreak is no exception. In Gauteng, more women (56%) than men have tested positive for the virus, according to the August 2020 Map of the Month of the Gauteng City-Region Observatory (GCRO).

The gender bias during pandemics is also visible in other studies, such as the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM). This five-wave-study, looking at five timeframes between February 2020 and April next year, is the largest non-medical Covid-19 research project in South Africa.

“Data from wave 1 show women in South Africa were especially hard hit by the crisis during February. Though women accounted for less than half (47%) of those employed in February, they accounted for two million, or two-thirds (67%), of the three million net job losses that were recorded between February and April,” says Daniela Casale, Associate Professor in the School of Economics and Finance. This unequal economic toll on women is frequently referred to as the ‘she-cession’, in reference to recessions.

The survey shows that while women accounted for two-thirds of job losses, men received two-thirds of the Covid-19 grants (65%).

One of the main reasons for this disparity in job losses is because of the continued concentration of women and men in different parts of the economy, and many of the hardest hit sectors were those that typically employ large numbers of women – tourism and hospitality, retail trade, personal care, and domestic and childcare services. In addition, women were found to have taken on more of the extra childcare work in April.

Women also lost their jobs across the spectrum in low-, semi- and high-skilled employment.

“What has been so devastating about this crisis is that everyone has suffered, but they have not suffered equally. Those who have been the biggest job losers have been at the bottom end of the skills distribution, so we know that most of the jobs lost were by women at the bottom end; women who in February were earning less than R1 500 per month,” says Casale.

Wave 2 of the survey, conducted since June and released in September, provided an opportunity to track how women have fared since the economy started to reopen, and shows women remain well behind men in reaching their pre-Covid employment levels. Women’s employment levels were still down 20% in June against February, while men’s were down 13%.

“A worrying finding is that even though women were over-represented among the job losses, they were under-represented in the income support received in June. Only 41% of the beneficiaries of the Unemployment Insurance Fund [UIF] or the UIF temporary employer/employee relief scheme, and 34% of those who had been paid the new Covid-19 social relief of distress grant, were women,” says Casale.

It is likely that fewer women received the social relief of distress grant because it cannot be disbursed concurrently with another social grant, such as the child support grant.

This means unemployed women are in effect penalised if they are also the main caregivers in families and communities, raising questions about the fairness of SA’s social protection system.

Double burden

“The Covid-19 pandemic has forced us to take a fresh look at the burden placed on women to manage responsibilities on a daily basis,” says Odile Mackett, Lecturer in the Wits School of Governance.

Women in paid jobs often still perform unpaid reproductive duties, such as housework and rearing children, in addition to their wage labour, and are estimated to spend up to five more hours a day on unpaid reproductive labour than men. To help women cope, these tasks have increasingly become ‘outsourced’ to people who live outside the household – domestic workers, nannies, and food delivery and take-away services rather than cooking at home.

However, women may then still be left to pay for or ‘manage’ the employees who perform these tasks, according to Mackett. Women’s extended working days have thus become normalised, despite the adverse effects that this has on their progression within the labour market and their general wellbeing.

This is amplified by the findings of the Wave 2 NIDS-CRAM survey, in which twice as many women as men said childcare has negatively affected their ability to work, to work the same hours as before lockdown or to search for work.

“From the evidence we have so far, the pandemic and ongoing lockdown are having a much more severe effect on women and their prospects in the labour market. This threatens to reverse some of the slow gains towards gender equality over the past 25 years in SA,” says Casale.

Tracking the shadow pandemic

The Covid-19 pandemic has highlighted the “shadow pandemic” of gender-based harm (GBH). Its extent during Covid-19 and the lockdown will only truly be understood in the years to come from data collected now and when pre- and post-pandemic trends and statistics can be compared.

Wits Journalism Lecturer Dr Nechama Brodie, author of the book Femicide in South Africa, which is based on her doctoral research, conceptualised the Homicide Media Tracker, now in development. The Tracker’s aim is to study violence in South Africa as reported in the media over the past 40 years. The idea is to build a tool that collects and keeps all media reports of homicide that can act as a baseline, including GBH.

“If we want to say that GBH during this pandemic is different, then different to what? Data and information gathered now, during the pandemic, will definitely come into play in future analysis,” says Brodie.

She cautions, however, that the trend has been to view everything, including GBH, through the lens of the pandemic and that to suddenly ignore and discard life before and after the pandemic is problematic – because while the pandemic will change many things, many things will not have changed, such as human nature.

“Violence against women is a societal problem and we cannot study violence without studying the society within which it takes place. As a society we have become good at performative acts of opposition to GBH; we sign petitions, post hashtags, change our social media profile pictures, but we do not actually perform acts that are useful.

“Information and data have value. With the Homicide Media Tracker, I want to build a baseline, because it can eventually become one tool that can be used by others who are studying violence, including femicide and gender-based violence.

“What South Africa did with this lockdown is the most bizarre and unexpected controlled experiment in terms of interpersonal violence, where we removed alcohol for three months. Only in the years to come are we going to see very interesting and probably very scary information about the levers that drive or amplify or minimise interpersonal violence and also violence against women. But at this stage we do not know the true extent of GBH during Covid-19,” says Brodie.

- Erna van Wyk is Senior Multimedia Communications Officer for Wits University.

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the 11th issue, themed: #Viral. Inspired by the SARS-CoV-2 global pandemic, content relates to both the virus that causes Covid-19, as well as the socio-economic, political, and environmental ramifications.