Building a better city

- Shaun Smillie

A ‘world class African City’ begins and ends with history and geography.

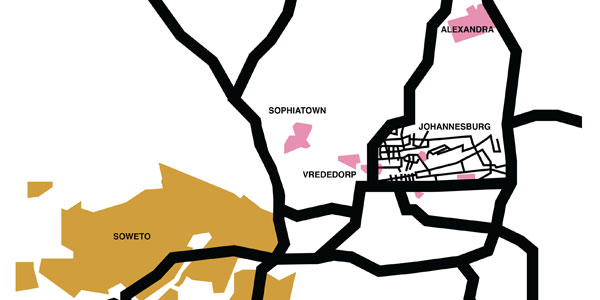

Segregation began the process of the dislocation of Johannesburg. This was formalised and enforced by apartheid legislation in 1948, and followed by the demolition of places like Sophiatown. By the 1950s, Soweto absorbed those forcibly removed people who had once enjoyed the benefits of living close to jobs and services, but who were now over 20km from the City.

“You had concentric circles made up of skin colour – Indians are allowed to live closer, then coloureds, then blacks. All locked into townships and barred off from the City,” says Professor David Everatt, the former Head of the Wits School of Governance. “And apartheid engineers ensured that highways, industrial plants and the like further emphasised the boundary between ‘white’ city spaces and black townships.”

Nearly three decades on, apartheid is history, but it still scars the urban landscape and looms large in the psyche of South Africa’s largest city. Its legacy is seen everywhere and is felt in the pockets of the poor.

“It is ‘hardcreted’ into the physical landscape of every South African town and city,” says Everatt.

Black workers still have to travel long distances from far-off townships to their places of work. It is also seen in the living conditions of new migrant families forced to get by in cramped, partitioned-off rooms occupied by multiple households, as they seek their fortune in the City of Gold.

City-saving geography

To dismantle this legacy is no easy task, but it can be done, experts believe. It needs dedication and some careful planning. One of the biggest challenges facing the City in its efforts to address inequality is simple geography.

Johannesburg lies in the smallest province, in which is crammed a quarter of the country’s population – and growing. In 2017, it was estimated that 547 people a day relocated to Gauteng from other provinces.

This is why Patricia Theron, a PhD candidate in the Wits School of Architecture and Planning, believes that Johannesburg cannot be considered in isolation from the other cities in Gauteng when it comes to creating equality for all its citizens.

"You can't develop one area alone and you can't consider the cities as competitors, but rather take a province-wide approach that is economically inclusive and holistic,” says Theron.

Mobilities and inclusive economies

There are efforts to work across these metropolitan boundaries and to address, in particular, integration of transport modes and high transport costs. The Integrated Public Transport Network Plan is a long-term strategy that aims to reform public transport across the three adjacent metropolitan municipalities bordering Johannesburg. An important part of the plan is fare policies.

But to introduce such plans and improve the lives of all Johannesburg’s citizens requires a strong inclusive economy that is not centred only in hubs like Sandton and the City’s northern suburbs. An effort is needed to boost township economies that have already been established but haven’t necessarily been recognised and encouraged.

Just like in the rest of Africa, the informal economy in Johannesburg has exploded in recent years.

The World Resources Institute released a report in 2018, titled: Including the Excluded: Supporting informal workers for more equal and productive cities in the Global South, that found that 76% of the workforce in Africa was in the informal sector, compared to the global average of 44%.

Policies and regulations, says Theron, need to better enable the daily operations and innovation in the informal sector – either to assist these businesses to become formalised if they want to, or to help in creating better opportunities and supporting collaborative networks. Regulations of these businesses could improve quality control, while formalisation enables the expansion of the tax net, she added.

“There has to be a mechanism for transforming the way the economy operates so that we are able to invest in different sets of skills bases that exist in townships,” says Everatt. “Create the jobs where the people are, rather than making them pay to get to jobs.”

A nod to the city nodes, but …

Over the decades, local government has introduced initiatives to try to speed up the transformation of the economy and stamp out racial inequality. Last year, the metropolitan government launched its nodal review, where the Department of Development Planning began a process of reviewing the ‘boundaries and controls of the urban nodes’ within the City. This followed the approval of the Spatial Development Framework 2040 for Johannesburg and the City’s Nodal Review.

“This identifies the best located areas in the City, where land is still reasonably affordable, and is best located in terms of access to jobs and services. And it plans to intensify in those nodes, … some of them adjoin middle class areas so there is resistance [including] threatened legal action by residents’ associations,” says Professor Philip Harrison, the South African Research Chair in Spatial Analysis and City Planning in the Wits School of Architecture and Planning. “But you are not going to change the City, unless you do that.”

Problematic boundaries

Changing the City requires transcending short-term politics and planning deep into the future. The problem, however, is the nature of local politics. Governments run on three-year budget cycles, says Everatt. Many of the long-term plans for the City were based on an assumption that the ANC would be in power 20 to 30 years from now. When the DA-led alliance took over the City, initiatives such as the Corridors of Freedom were downgraded. For these long-term plans to work, they need limited goals that survive political regime changes.

“If you want to change this, you have got to have the courage to make investments in infrastructure that should have a 50 to 80 year window,” says Everatt.

Built to last?

A problem facing urban planners now is the Covid-19 pandemic. Funding has dried up. This means that, for the time being, Johannesburg will continue to be the most unequal large city in the world. It is a city still gouged by racial lines. The new divide is between north and south.

To the south are the poor blacks who, as during apartheid, are gathered on the periphery of the City, this time around places like Orange Farm. Meanwhile, north of the city ‘white flight’ has moved into the endless new developments of townhouses and cluster homes.

The irony, Everatt points out, is that studies show that both racial groups take the same amount of time to commute to work, albeit from opposite poles of the province and the City.

“The apartheid spatial design has incredible powers of endurance – it has barely shifted an iota. The middle and the upper classes have been fine and have integrated in suburbia, but life in the townships is becoming harder and harder.”

- Shaun Smillie is a freelance writer.

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the 12th issue, themed: #Solutions. We explore #WitsForGood solutions to the structural, political and socioeconomic challenges that persist in South Africa, and we are encouraged by astounding ‘moonshot moments’ where Witsies are advancing science, health, engineering, technology and innovation.