Being queer in Africa

- Beth Amato

Despite a history of openness to queerness in pre-colonial times, Africa is now largely unwelcoming to LGBTQIA+ people.

In halls at undisclosed locations in Zambia, you might think that you were on the set of Pose, a drama series based on drag ball subculture among black and Latino LGBTQIA+ people in New York City in the ‘80s. In these halls, difference and repressed expression are celebrated and encouraged. Zambia’s queer community, in their ball gowns and under those moving twinkly squares of a disco ball, take centre stage. There is lively catwalk commentary and the outside world, with its terrible risks and dangers, is quiet.

Hopes and Dreams that Sound Like Yours: Stories of Queer Activism in Sub-Saharan Africa. © Taboom Media & GALA Queer Archive, 2021 | Illustrations by Larissa Mwanyama and Amina Gimba

In Zambia it is illegal to be gay. Policies are deeply rooted in heteropatriarchal and religious values and beliefs. “Zambia is undoubtedly and irrefutably a Christian country. In that country, homosexuality and anything other than a binary definition of sex and gender is an anathema to Christianity,” says Efemia Chela, a Master’s student in the Governing Intimacies Project at Wits University. Chela is trying to understand what it is like to be queer in Zambia, and how sex and gender are constructed in Zambia’s broader imagination. Her research is the first on lesbian, bisexual, queer and non-binary people in Zambia.

Africa Check published findings by the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Gay, Trans, Intersex Association (ILGA), which showed that 31 out of the 54 UN member states in Africa criminalised consensual same-sex sexual acts between adults in private. Meanwhile, same-sex marriage is only legal in SA.

ILGA’s 2020 State Sponsored Homophobia report reveals that in Egypt, for example, “even though there are no laws explicitly criminalising consensual same-sex sexual acts, other laws are used in practise to arrest, prosecute and convict people of diverse sexual orientations and gender identities.” Hence, this is de facto criminalisation.

In states where Sharia law is applied (such as Mauritania, Somalia, Nigeria and South Sudan) being gay is punishable by death.

Indeed, while many countries do not directly criminalise transgender and gender-diverse people, many do so indirectly through indecency laws, the criminalisation of same-sex relationships, and impersonation laws. It is almost impossible in Africa to change gender markers on legal documents, although this may be changing in the near future.

Only three states – SA, Mauritius and Angola – explicitly condemn discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. Despite this, there is no guarantee that people across the queer spectrum live safely and openly.

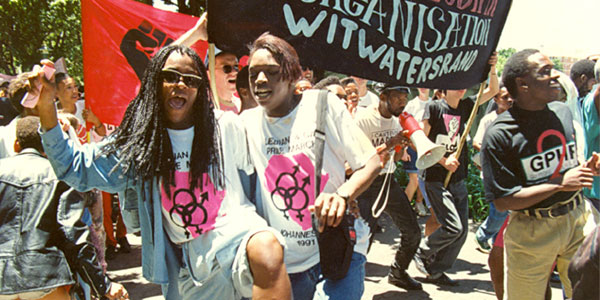

Jo'burg Pride 1996 © Ditise Collection | GALA Queer Archive

History tells another story

Why is it so challenging to be queer in Africa when research shows that there is a rich queer history on the continent.

“In pre-colonial times, being queer was acceptable. We have queer ancestors all over the continent. That history has been demonised, erased and further supressed by religion,” says Boniswa*, a 28-year old who identifies as queer.

She explains that her great-grandmothers had words for being gender non-conforming. Indeed, those who transcended gender binaries were considered spiritual healers because they embodied masculine and feminine qualities.

"We have queer ancestors all over the world"

Catherine Burns, an Associate Professor in Medical History and Ethnography at Wits University, notes that gender and sexual diversity in Africa has been around for many generations. “Indeed, the Modjadji monarchs or the rain queens of the Balobedu in Limpopo, South Africa, are not supposed to marry, but have many ‘wives’, although they are not spouses in the typical sense. Moreover, while Modjadji procreated with male suitors selected by her clan, she was not required to remain in exclusive relations with them,” she explains.

Burns says that the ‘self’ was never strictly seen in binary and gender specific terms. Fluidity, play and the embracing of a multi-faceted ‘self’ strengthened bonds and aided community cohesion. “We need to start taking all intimate experiences seriously. We need to ‘open’ up our language to give space to gender fluidity and difference,” adds Boniswa.

First Cape Town Pride 1993 | © Theresa Raizenberg Collection, GALA Queers Archive

The dangers of being queer today

Fast-forward to 2021, and being queer in Africa is complex, gritty and granular. Entangled with a validating queer ‘ancestry’, as Boniswa puts it, is tangible and intangible discrimination. On the most horrific end of the spectrum, there are hate crimes, where lesbian and trans people in particular are at huge risk of violence and death. It is worse for poor, black queer people.

“Already there are so many odds stacked against you when you identify as queer. Your families and churches may have shunned you. Then you live in poverty-stricken circumstances in highly unequal societies. In 2020, when lockdown began, we had to go beyond our role as queer memory archivists and help people who were starving, out of work and isolated with no support structures. The stories made us weep,” says Keval Harie, Director of the Gay and Lesbian Memory in Action (GALA) Queer Archive at Wits University.

While there are stories of hardship, pain, rejection and discrimination, there are many ways in which heteronormativity and patriarchy are challenged. Indeed the GALA Queer Archive showcases stories of change, especially through storytelling, history, education, advocacy and art.

“There isn’t this universal and monolithic queer-lived experience in Africa,” says Boniswa.

For her, more ‘liberal’ spaces like Braamfontein have been surprisingly unwelcoming. She recalls how the waiters in a pizza restaurant refused to serve her and her girlfriend after they saw them holding hands. When she came out as queer, Boniswa’s heterosexual female friends shunned her. She has to argue with those who think she is ‘anti-man’, because she challenges dominant monomyths.

“No matter the huge risk to them, queer people find ways to subvert authority and express themselves wholeheartedly,” says Chela. A thriving drag ball and Pride subculture in Zambia extends to an active supportive community. There are ‘chosen family’ gatherings, underground Pride events and closed Facebook and WhatsApp groups. Important information is shared, such as which mental health workers, medical doctors and state officials are queer friendly.

Boniswa deeply admires the work of queer artist and activist Zanele Muholi. In Muholi’s recent work, exhibited at the Tate Modern in 2020, the artist’s photographs give voice and agency to the lesbians, gender non-conformists and trans men depicted in the work. The exhibition is a prosaic take on the everyday reality of those believed to be ‘threatening, un-sacred and tragic’. Muholi aimed to re-write a black queer and trans visual history of SA “for the world to know of our existence, resistance and persistence”.

“While I can’t say whether being queer will ever be formally acknowledged and decriminalised in Africa, there are many pockets of people who express themselves in the ways that they can, and establish robust social networks, no matter how marginalised and despised they are,” says Chela.

*Boniswa prefers to use only her first name in this article. She is a member of the Wits Community.

Safe Zones

The Safe Zones @ Wits programme strives to erase prejudice, while providing a support system for the LGBTQIA+ community at Wits University. Through education, advocacy and awareness-raising, the programme contributes to a campus climate that is safe and accepting.

University members are asked to consider becoming a Safe Zone ally. After members have completed training, a badge and sticker can be displayed indicating a Safe Zone. Ultimately, an ally is defined as an individual who supports and honours diversity, challenges acts of prejudice against LGBTQIA+ people and is willing to explore and understand these forms of bias at the individual and institutional levels.

The Pocket Queerpedia 2021, made available by the Tshisimani Centre for Activist Education, is an illustrated glossary of LGBTQIA+ terms. The book came into being after activists realised how LGBTQIA+ terms were not commonly understood. “Why are some terms used in different ways by different people? What is the difference between a transgender and a gay person? Can a person be transgender AND gay? What does the word queer mean, and why should I care if I do not share any of these experiences?” are questions asked by participants in the making of the book. The full version is available at: https://www.tshisimani.org.za.

The GALA Queer Archive (GALA) is a catalyst for the production, preservation and dissemination of information about the history, culture and contemporary experiences of LGBTQIA+ people in SA. As an archive founded on the principles of social justice and human rights, GALA works toward a greater awareness about the lives of LGBTQIA+ people as a means to an inclusive society. GALA's primary focus is to preserve and nurture LGBTQIA+ narratives, as well as promote social equality, inclusive education and youth development.

- Beth Amato is Communications Manager at the African Centre for the Study of the US at Wits University.

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the 13th issue, themed: #Gender. We feature research across disciplines that relates to gender, feminism, masculinity, sex, sexual identity and sexual health.