Anticipating a 'second wave'

- The Scientists Collective

Covid-19: When and how South Africa should try to prevent or mitigate it.

In recent days, health minister Zweli Mkhize has warned about a marked increase in new Covid-19 infections as a result of declining adherence to measures such as mask-wearing, physical distancing and hand washing. The United States and many western European countries are experiencing a dramatic resurgence, often called a ‘second wave’, of the coronavirus.

Does this mean a second wave is inevitable in South Africa?

In South Africa, the possibility of such a resurgence has seemingly justified the extension of the powers of the National Covid-19 Command Council (NCCC), under the legal framework of the National Disaster Management Act.

What is the rationale for European countries to impose lockdown strategies to manage the resurgence?

The United Kingdom, France, Netherlands and Spain have introduced a new round of curfews and are considering lockdowns as a means to contain transmission. Such interventions might well be effective in these and other countries, especially if they are able to support a lockdown from a societal and economic perspective.

These measures are also underpinned by the low levels of immunity in the general population in the affected regions. The majority of EU member states still have low levels of seropositivity (see Germany here and Spain here) to antibodies directed to SARS-CoV2, ranging between 0.9%- 8.5%. Regions in some countries are outliers such as Austria, with more than 40% seroprevalence of Covid-19 antibodies detected in its populace due to heavy infection in the first wave.

These data suggest that in certain European countries, such stringent measures may retard transmission and therefore the overall number of cases and deaths.

Should the same rationale apply in South Africa?

We believe the context is different in South Africa.

Countries implement public health measures to get transmission under control. To get transmission under control, countries have two choices.

First, they can try to reduce transmission in order to reduce a peak health demand. This is called mitigation. Mitigation can be achieved by isolating cases and quarantining close contacts (requiring a robust test and trace capability), adherence to social or physical distancing, wearing masks, hand hygiene and protecting that part of the population with the highest risk of serious illness if they are infected. Collectively, these measures are termed non-pharmaceutical interventions, or NPIs.

Second, a country might attempt to suppress the epidemic and attempt to stop transmission. This is called suppression or lockdown and aims to reverse epidemic growth, reducing case numbers to low levels by physically distancing the entire population indefinitely.

Seven months into the pandemic, it is evident that while SA’s hard lockdown at an early stage of the epidemic initially slowed transmission, and that some healthcare facilities in certain areas of the country were able to prepare for the expected increase in admissions, this was uneven and did not manage to stop transmission. There is even less chance now of being able achieve sustained suppression of virus circulation in South Africa through a lockdown, than was the case when circulation initially started.

South Africa, despite having one of the earliest and harshest lockdowns for a protracted period of time did not achieve suppression, nor was it likely to.

The reasons for this are self-evident:

- The lack of an integrated approach to the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak, from initiating community screening and tracking Covid-19 disease outcomes;

- The inability to scale-up community testing in time, with concomitant long turnaround times and inadequate contact tracing that would enable the timely isolation of cases and close contacts. Contact tracing was not achieved at the scale required to suppress the epidemic, despite SA having one of the largest testing programmes in Africa.

- Compliance with lockdown rules and NPIs suffered a trust deficit arising mainly from poor communication, heavy-handed enforcement and random bouts of misinformation from dubiously qualified private lobbies.

The international experience is illuminating.

Except for a few island nations, most countries failed to achieve sufficient viral control, whatever mitigation or suppression measures were applied. The World Health Organisation (WHO) actually concurred with the view of some local scientists who had cautioned against a hard lockdown as a primary strategy prior to its imposition.

It was clear that a lockdown alone will not eliminate or permanently control the spread of the virus unless it was coupled with an efficient system of testing suspected cases of Covid-19 and ensuring their isolation, as well as exercising a high level of contact tracing and their proper quarantine.

The reality is that the massive societal, economic and health resources needed to emulate countries like South Korea and China, which were initially able to achieve impressive levels of suppression, were not available to countries like SA. Moreover, while the rate of virus infection can be controlled through measures such as NPIs, adherence to even these measures are challenging in most low income settings where overcrowding is a grim reality, and even access to water is compromised.

Consequently, the highly restrictive and even coercive lockdown measures deepened social discontent the longer the measures were in place; the enforcement of which deepened mistrust of the authorities and may have contributed to poor compliance with mitigation measures in all groups and classes of society.

Alongside an inadequate testing and tracking infrastructure, this resulted in only a temporary reduction in community transmission of the virus over the first three to four weeks of the lockdown.

However, failure of being able to test for Covid-19 at scale in the public and private sectors, plus the incoherent prioritisation in the testing regime and the delay in turnaround times of tests, as well as the incapacity related to the tracing of contacts and their quarantine, have led to the predictable consequence that community transmission persists and may yet seed another increase in cases.

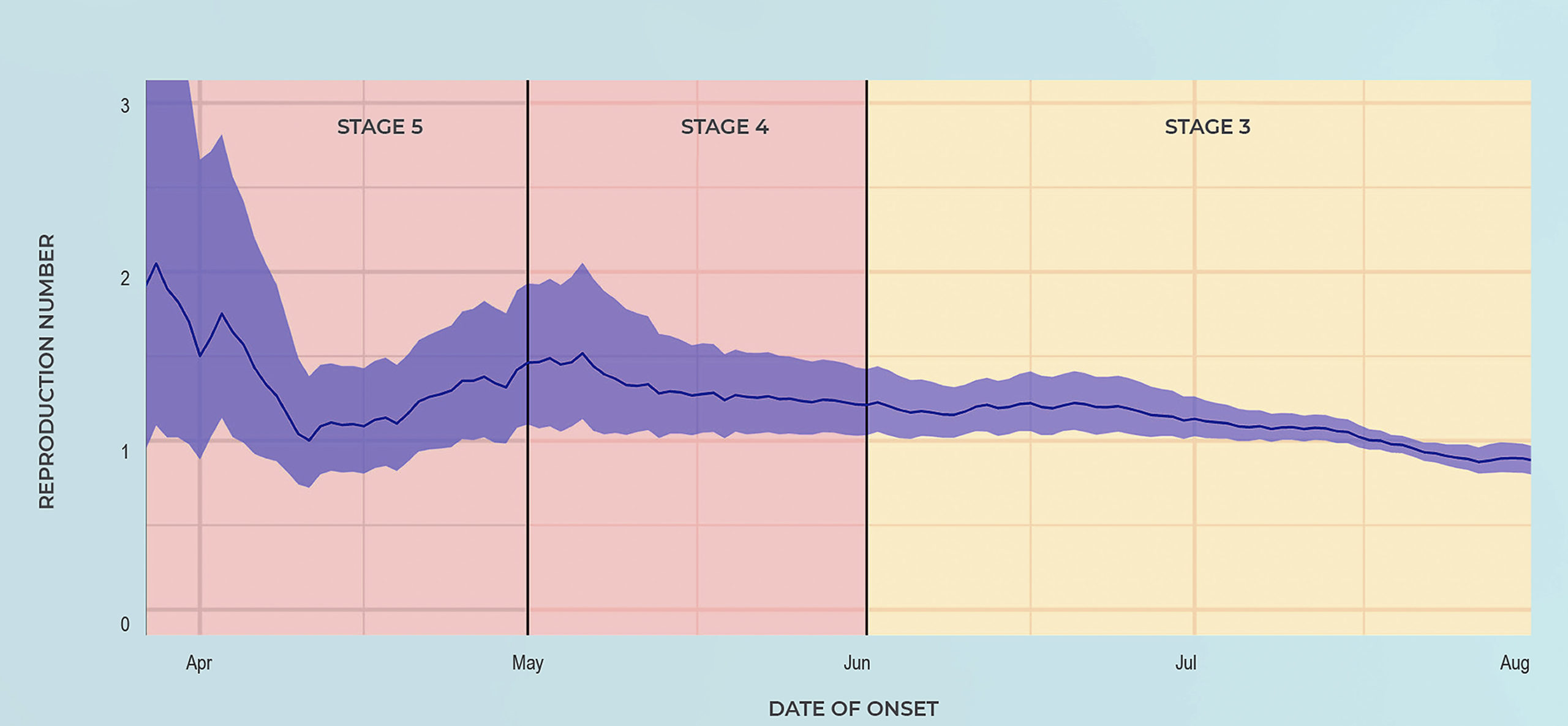

Reproductive Rate of the South African epidemic under various stages of lockdown

This persistence of transmission is evident through an analysis of the effective reproduction rate (Re) of SARS-CoV-2 as modelled by the National Institute for Communicable Diseases (NICD). The effective reproductive rate determines whether the number of cases of Covid-19 in the population will go up (when Re >1) or down (Re <1).

In South Africa, during the Level 5 lockdown, the Re ranged from around 1.5 to 2, indicating ongoing community transmission even during the lockdown.

The Re only declined substantially after the surge in July, following large scale exposure to the coronavirus in various communities in the Western Cape and Gauteng, thereby reducing the number of people susceptible to infection.

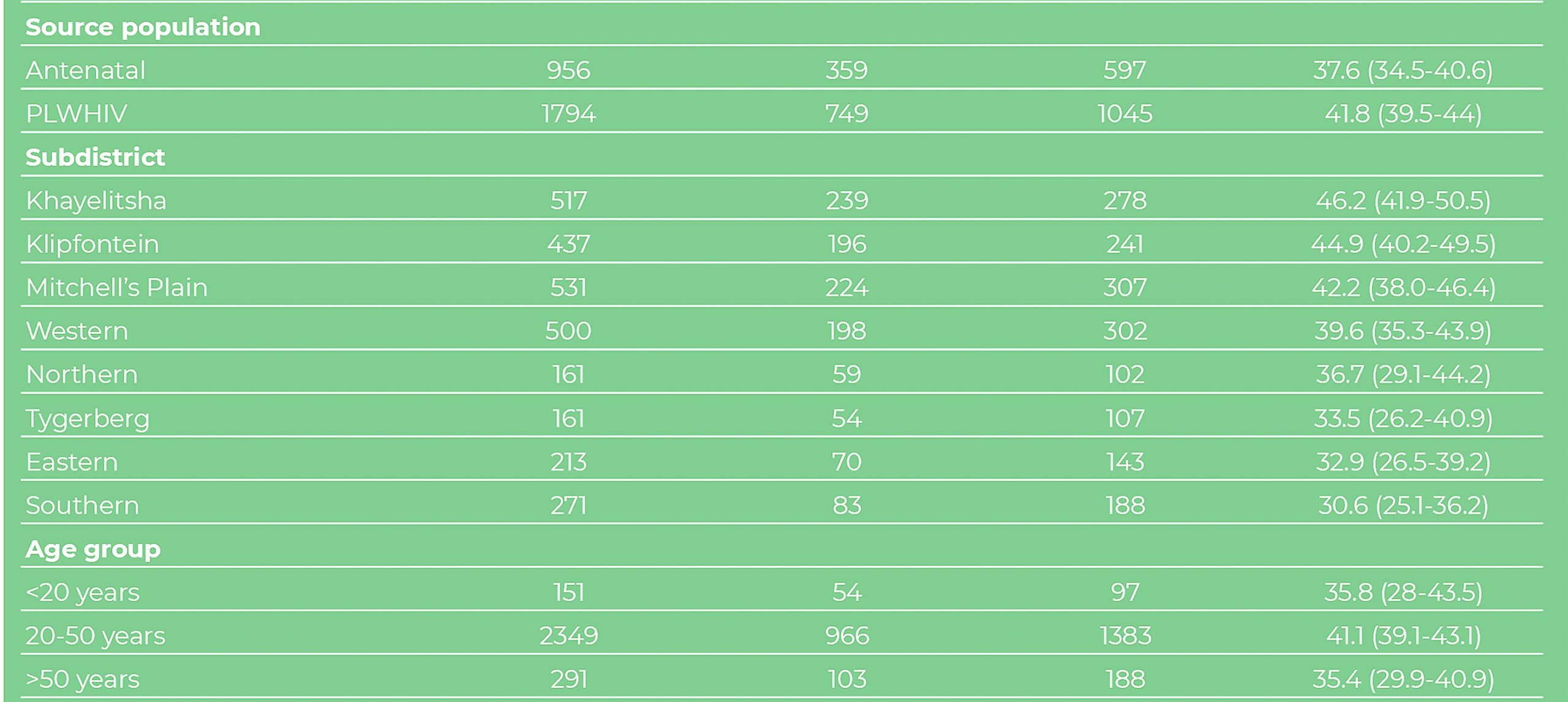

At the time of lockdown Level 3, up to 40% of the population in the Western Cape (and empirically a similar percentage in major urban metro areas in Gauteng) demonstrated evidence of SARS-CoV-2 infection, including presence of antibodies to Covid-19.

Seroprevalence surveys in Western Cape

Did lockdown or mass exposure to SARS-CoV-2 lead to subsidence of the first wave?

Data suggest any claim that the highly restrictive lockdown was successful in preventing community transmission of the virus, and contributed to the first wave waning, is inaccurate. Paradoxically, infection rates only started declining and the Re trended downward to approximately 1 from July onwards, as restrictions were being eased and social and economic activity increased commensurately.

The proposition that the interruption in the chain of transmission of the virus – due to an increasing proportion of the population being gradually infected over time and developing at least partial immunity – is supported by surveys undertaken across different districts in the Western Cape, where 40% of women attending antenatal clinics, and people living with HIV, had evidence of infection in different sub-districts, suggesting that a massive “covert” wave of infection, far greater than in Europe, North America or Asia (excluding South Asia), occurred.

Certain practices such as maximum taxi occupancy and resumption of attendance at places of worship, which were incrementally allowed during relaxation of the lockdown, undoubtedly increased the risk of virus transmission to people still susceptible to infection.

Despite some reluctance to comply due to inadequate communication coupled with harsh enforcement, the partial adherence to NPIs may have somewhat mitigated the potential consequences of these actions and was the most effective aspect of our public health interventions.

Notably, the recommendation by the previous ministerial advisory committee for the use of non-surgical face masks – and emphasising the potential airborne transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in South Africa – preceded WHO recommendations and advisories on these measures.

Paradoxically, the approach to lessening lockdown restrictions as the epidemic gained momentum in South Africa, likely led to a massive surge in coronavirus infections during our winter months, inducing at least some immunity in a high percentage of the population, particularly in densely populated areas.

This most likely led to an interruption in the chain of transmission of the virus in South Africa, which, together with at least partial adherence to NPIs, resulted in the first wave of the epidemic waning.

However, the proportion of the population that has been infected is likely far less than what is estimated (60-70%) to enable sustainability of low rates of infection (Rt<1.) – so called “herd immunity”.

There is also evidence of increasing complacency around the adoption of NPIs.

Therefore a resurgence of Covid-19, consequent to declining adherence, is likely to be experienced in the short term. Furthermore, uncertainty regarding the longevity of immunity following infection makes projections difficult on the future course of the pandemic.

What can we learn from other countries and does it predict what will happen in South Africa?

One observable similarity between South Africa’s and Europe’s epidemics has been a reduction in cases correlated with a change to warmer seasons. Although climatic factors may play some role in the transmission of SARS-CoV-2, the role of changing human behaviour in reaction to the weather is probably the deciding factor.

Spending more time outdoors and the ability to ventilate closed (taxis, trains etc) and indoor spaces is a critical factor.

One lesson, however, is important: the opening up of European societies during the summer months was likely coupled with less adherence to NPIs, which allowed for a resurgence of infections and Covid-19 hospitalisations.

In South Africa, our adherence to these tried and tested public health interventions to control Covid-19 must continue unabated. This is absolutely critical if we are to be spared the worst ravages of the kind of resurgence being witnessed in the northern hemisphere.

Different testing rates and testing strategies in many of the European countries (including Spain and UK), make it impossible for head-to-head comparison of the scale of the resurgence, relative to what was experienced in their first waves. Similarly, we cannot make meaningful head-to-head comparisons between (and even within) countries in respect of the number of infections or death rates that may result here.

This makes the task of gaining any insights into what could happen in South Africa inordinately difficult. After all, the hard lockdown initiated in SA followed the examples of China, South Korea, Iran and Italy, all of which experienced high-surge phenomena, even before the virus took hold in the South.

As we have noted above, this was perhaps not the optimal response, given what we already knew about local epidemiological trends and the extreme unlikelihood of countries in Africa being successful when aspiring for containment of a respiratory virus.

Resurgence is likely but our response should be different

A resurgence of Covid-19 is certain to occur in South Africa, although indications are that a second wave is likely to be different to the wave currently sweeping over Europe.

It is possible that, because a large percentage of people who live in major urban metros with a high population density have already been infected, this will assist in limiting the rate of transmission in such settings.

Put another way, a resurgence in settings where there was a high force of infection during the first wave, is likely to be of a lower magnitude than experienced with the first wave. Conversely, communities with low rates of infection in the first wave, may be disproportionately affected during a resurgence of Covid-19.

Seroprevalence surveys designed to characterise the proportion of communities that have been infected during the first wave in all sub-districts of South Africa will be a vital indicator of where a resurgence of infection might be concentrated.

Provinces and communities which experienced a lower rate of infection in the first wave may be settings for higher rates of infection and mortality in a second wave if mitigation measures are not implemented.

Strategies to meet this expectation, including smart, targeted and strictly limited restrictions, must be urgently devised and based on credible and swift seroprevalence surveys and a rational and outcome-driven testing programme.

Active adherence to public health measures and building robust test and trace infrastructure, as well as strengthening healthcare infrastructure in anticipation of an increase in cases, are likely to be the deciding factors in how well the country navigates resurgence of Covid-19.

What we can be certain of is that the type of hard lockdown imposed in March will only inflict further, perhaps fatal, damage to an economy which was on the ropes before the pandemic – and which the hard lockdown rendered moribund.

It will also significantly undermine any chance of an economic recovery, without achieving any meaningful net health impact.

It is, moreover, unlikely that a Covid-19 vaccine will be available to South Africa before the end of the next winter. Consequently, the only instruments in our current toolkit to blunt and minimise the consequences of a resurgence is to actively motivate society to continue adhering to NPIs.

Even if NPIs are not always implementable at scale in our own context, they nevertheless contribute massively to the control of the rate of transmission of the coronavirus and would assist in avoiding overwhelming the beleaguered healthcare delivery system.

It is axiomatic that only the people can overcome a pandemic, as observed throughout history.

It is, therefore, the work of governments to act in support of – and not second guess – the scientific and health system imperatives.

To single-mindedly focus on providing the people with all the necessary information and support, and to eschew self-serving political considerations in this effort, represents the most important contribution of South Africa’s political leadership in this time of crisis.

Professor Shabir Madhi, Respiratory and Meningeal Pathogens Research Unit, University of the Witwatersrand; Professor Glenda Gray, South African Medical Research Council; Professor Francois Venter, Ezintsha, University of the Witwatersrand; Professor Marc Mendelson, University of Cape Town; Dr Lucille Blumberg, National Institutes of Communicable Diseases; Dr Aslam Dasoo, Convener of Progressive Health Forum.

This article was first published in Daily Maverick/Maverick Citizen.