Talking tech and African languages

- Buhle Zuma

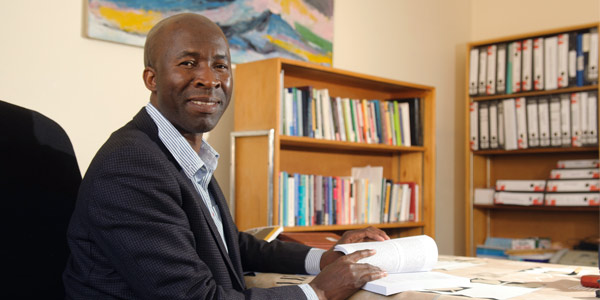

Is tech killing indigenous African languages? Prof. Leketi Makalela, head of Languages, Literacies and Literatures in the Wits School of Education talks back.

Discussions on the status of African languages portray a dim view. For centuries, African languages have been under threat as one conqueror after another has imposed their preferred language on various nations on the continent. Subsequently, African languages have low status in our institutions and continue to be marginalised in all spheres of power, including government quarters.

In South Africa, English continues as the lingua franca, despite government policies that protect and promote vernacular languages.

There have been warnings about the death of these languages. However, indigenous languages are far from extinct says Professor Leketi Makalela, Head of Languages, Literacies and Literatures in the Wits School of Education.

“Where government has failed, technology is bringing hope to the people,” says Makalela. “African languages were probably going to die, were it not for technology, social media and popular culture. Technology is going to take African languages forward and these languages are going to evolve to fit into the digital age and any future world shift.”

Ironically, this change is one of the major criticisms levelled against technology, and especially social media, where variations of spelling abound, and where the platforms are also implicated for contributing to the decline in literacy and writing standards.

“People are concerned about change and this has been an ongoing major debate in human language development. The great divide is about whether the change results in decay or progress. A conservative will say it is decay because there is nostalgia for the past and everything is being disorganised by modernity. This has to do with aging as well – the older you are, the more you want to keep things the same,” says Makalela, who is also the Editor-in-Chief of the Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies Journal and Chairperson of Umalusi Council’s Qualifications Standards Committee.

To put things into perspective, Makalela says the primary question that needs to be asked in such debates is: “What is the purpose of language?”

“We need to question what language is and why we have language as human beings before we look at the structure (syntax and spelling). People obsess about the aesthetics of the language and yet language is here for meaning-making. The ‘net speak’ and contraction of words are a natural evolution of language and a reflection of the time. The structure of language keeps changing because people are changing.”

One of the significant, laudable changes brought about by social media is that they break down linguistic barriers. Makalela believes we should celebrate that communication technology is contributing to the decolonisation of languages.

“The Balkanisation of African states in 1884 in Berlin was attached to the languages. The Bantustan policy of apartheid architect H.F. Verwoerd was based on supposed linguistic differences,” says Makalela. “African languages were separated intentionally, not because they were or are different, but because the strategy was to divide and conquer. Technology has now made it easy for linguistic groups to realise how similar they are than they were previously told.”

Communities such as #BlackTwitter, mother-tongue appreciation groups on Facebook and blogs where young creatives share works in their languages and culture are defying institutions and moving languages into the 21st Century. Local television programmes are also playing their part in promoting multilingualism with many creative works moving between three and more languages, recreating and reinforcing the South African linguistic reality.

“We cannot talk about economic development and social cohesion without taking into account the issues of language because languages are central to social cohesion. You can’t expect a Zulu and a Tswana person to socially cohere if there is no crossover of language,” he adds. “One of the barriers that must be removed to drive this growth is for linguistic groups to be open to the influence of non-mother tongue speakers,” explains Makalela.

“There seems to be a sacredness and unwillingness to allow others to learn African languages, which often makes it closed to outsiders. If we really want our languages to flourish, we have to open the doors to non-mother tongue speakers so that there is nothing like KZN isiZulu vs Gauteng isiZulu (which is seen as weak isiZulu). In fact, it’s a time to redefine what we call standards.

English became a dominant language because it opened its doors to non-mother tongue users. The type of English used today is heavily multi-lingual with 80% of the words in the language not original English. In addition, 80% of users are not traditional mother tongue speakers. English thrives and lives on donations from other languages.”

Another area where Makalela would like to see transformation is the use of technology in the classroom to promote multilingualism. “While technology is often seen as eroding African values, accelerating moral degeneration and the loss of ubuntu, practice is suggesting that it is having an opposite effect on languages. Let us focus on creating shared meaning and understanding through opening up our languages and using technology to contribute towards fostering social cohesion in our diverse society.”