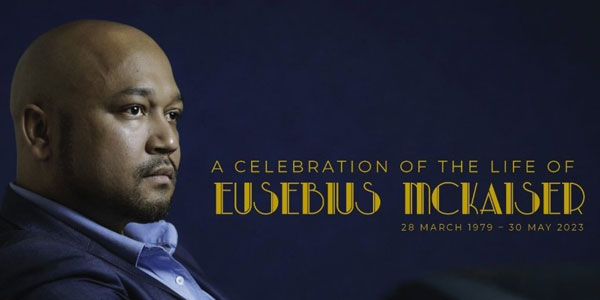

SA philosophers mourn the passing of Eusebius McKaiser

- Wits University

On behalf of Wits Philosophy and the South African Philosophy community, Professor Lucy Allais honours Eusebius McKaiser.

The South African philosophy community mourns the passing of Eusebius McKaiser (28 March 1978 – 30 May 2023), well-known and celebrated public philosopher, political analyst, author, commentator, and broadcaster. At the age of 45, he died of a suspected epileptic seizure.

McKaiser was born in Makhanda, formerly known as Grahamstown, and grew up in a poor, working class, coloured township at the height of apartheid. (For non-South Africans, in South Africa ‘coloured’ designates one of the four apartheid racial categories: black, coloured, Indian and white.

McKaiser has been described as culturally coloured and politically black, and was proud of both labels. The political meaning of black in South Africa represents solidarity between the three groups discriminated against by apartheid. ‘Black’ is not capitalized in South Africa. The need to explain these details, in relation to the different racialized categories in other countries, would have amused McKaiser, who wrote two books on race, and regularly discussed it in his broadcasts and commentaries.)

From a beginning in apartheid’s systematic and intentionally bad schooling for black children, he ended up studying philosophy at Oxford, though McKaiser was quick to point out that he was plucked out of a poor school, as extraordinary teachers and family spotted his brilliance early, and channeled him into better ones. At school, his loves were piano, chess and debating, and he went on to become a national and international debating champion. McKaiser majored in philosophy and law at Rhodes University, earning his bachelor’s degree with distinction, followed by an honours degree and a masters degree in philosophy. He attended Oxford University on a Rhodes scholarship, where he did doctoral research under Ralph Wedgwood and John Broome, but never completed his D.Phil.

After a brief period working as a consultant at McKinsey, he remade himself as a public commentator, political analyst, public philosopher, and broadcaster. He wrote for the New York Times, Business Day, Mail & Guardian, Sunday Times, Sunday Independent, City Press, Newsweek International, BBC Focus on Africa, The New Republic, Financial Mail and Destiny Man, was a radio talk show host on Power FM and Radio 702, and hosted two podcasts. He published three books, works of public philosophy and social and political commentary. He was comfortable in many worlds, moving between a poor background and affluence with ease, and delighting in code switching.

McKaiser was extremely well-known as a commentator and public figure, but his first love was philosophy, and he thought of himself as a philosopher. His exceptional talent was using his brilliance, his philosophy training, his charisma, energy, intellectual discipline, humour, and fearlessly independent views to raise the level of debate in public life in South Africa. He loved to debate, he loved argument, he loved rigour, logic, analysis and nuance. He loved sharp thinking, and had no time for what he regarded as sloppy thinking or mediocrity. He also had no time for academics who make public arguments but cannot translate them out of jargon and into ordinary language.

In a personal tribute his friend and fellow journalist Rebecca Davis writes: “Before Eusebius, it was impossible to imagine a mainstream radio host holding discussions of philosophical issues — as in, issues central to the academic study of philosophy — during primetime. He did it routinely, and he raised the bar for everyone, in a notoriously anti-intellectual country.” He was interested in law, and combined a sharp ability to name what was at stake at a fundamental level for our society’s wellbeing with a unique ability to read and distil arcane legal judgments into terms understandable to the public, showing, again and again, why constitutional principles matter.

McKaiser, as Davis puts it, was boldly and unapologetically himself. He had strong views, which he expressed forcefully, never pulling his punches, and provoking strong reactions – few in his audience had neutral feelings for him. He refused to allow his being gay to be anything but a given.

He identified as a progressive liberal, or a radical liberal, a bold public statement in a country where the word ‘liberal’ (often heard as ‘white liberal’), is associated with extreme free market fundamentalism and ‘colour blind’ policy, and is thought of as having no concern with social welfare. McKaiser rejected these associations, identifying with Charles Mills’ project of ‘occupying liberalism’, and pushing back on the DA’s (opposition Democratic Alliance) claiming of the word liberal for policies he considered, in contrast, libertarian. For example, in his recent podcast reflecting on Freedom day and Workers’ day, he presses us to ‘be rigorous in our conceptualisation of “freedom”’, and concludes with reflections on the moral limits of markets, arguing that ‘If we want our democracy to flourish, and for all of us to realise our potential, then there is simply no room for the fantasy that questions of fairness or justice can be settled with deference to economic markets. There is no point in pitting the exploited worker against the unemployed.’

He courted controversial topics, as well as playful and light-hearted ones. In a country in which many people are religious, he loved hosting debates on whether God exists, including one on the connection between God and morality at the great hall at Wits, and published a piece on the topic on Easter Friday. He forcefully drove public conversations on race, and kept a focus on the widespread violence in our society, on poverty and inequality, the crisis of rape, bullying in schools, and mental health. He was fiercely independent, and was known for holding politicians’ feet to the fire. Despite being thought of as arrogant, he was vulnerable, interested in vulnerability, and pushed his interlocutors to be vulnerable and to challenge notions of masculinity, and talked openly about weaknesses, as well as about changing his mind.

As an associate of the Wits Centre for Ethics, housed in the philosophy department at the University of the Witwatersrand, he co-organized a number of highly successful public debates and talks on a variety of topics, from opposition politics, infectious disease, decriminalizing sex work, to Samantha Vice’s whiteness paper. Vice’s paper catapulted from small academic circles into the public, sparking weeks of the ‘whiteness debate’ on the Mail and Guardian online, after McKaiser wrote a column about it, and later wrote a response in an edition of the South African Journal of Philosophy on Vice’s paper.

He also regularly and brilliantly chaired philosophy debates and talks at the Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research (WiSER), South Africa’s premier academic hub for the humanities, including on the topics of problematizing western philosophy, Ubuntu, and Kant’s racism. In addition to his scintillating ability to command audiences, and his effectively summarizing, framing and interrogating the speakers, he used his skill on social media and his vast networks to promote these events to great effect, often live tweeting the arguments presented, capturing what each person was presenting with nuance, accuracy and accessibility, affording university philosophers a reach we could never have had without him. In the case of the sex work debate, this included making prime time TV news. He participated in, drove and designed public debate in many other forums, including regular events at the Apartheid museum.

For a while not having finished his PhD rankled, and he even looked into finishing it through Wits. But after time he realized that he simply didn’t need it – he was where he wanted to be, doing the work he wanted to do. Apart from a term teaching ethics and philosophy of race at Wits, he never taught at a university, but he loved educating, working as a debating coach with young people and a mentor to many.

In her tribute to him, fellow journalist and broadcaster Joanne Joseph described his radio work as being as much educational as entertainment, saying: “He made demands on his listeners to think critically, to reconsider their previously held views, to break down tropes and stereotypes and to learn the power of thoughtful argumentation. He gave them the vocabulary, creating pathways for them to access academic theory, and the practical levers to process the meaning of their lives, from the political to the personal. He offered them a forum, but made it quite clear in a world where opinions have come to matter more than facts, that we are only entitled to our justified opinions, not our alternative set of facts. In so doing, he grew a generation of empowered radio listeners who began to consume media more astutely and respond more thoughtfully and analytically, and hopefully who imported that faculty into their daily decision-making and worldview.”

In a country that recently scored among the lowest measured scores in the world for the ability of primary school children to read for meaning, McKaiser was passionate about promoting books and reading, and about promoting South African authors, which he did with enormous generosity, on social media, at book launches, and co-hosting with fellow broadcaster Joanne Joseph a program on books called ‘Cover to Cover’. He had deep affection for his school teachers, many of whom he kept in contact with. He regularly posted pictures of himself on social media with the latest book by a South African author he was reading.

His final podcast, made the night before he died, is a classic McKaiser argument – a bold, fierce engagement with the complex dysfunctionality of all of South Africa’s main political parties.

Expressions of grief have poured out across the country and around the world, including from President Cyril Ramaphosa's spokesperson, Vincent Magwenya, saying the broadcaster was "a brilliant mind".

He was irreplaceable, and leaves a huge hole in our public life, and in our hearts. Our thoughts are with his partner Nduduzo, his family and friends.