Rick Turner and the enduring necessity of utopian thinking

- Halton Cheadle

Utopian thinking, revisiting the ideas of Rick Turner in the current political context.

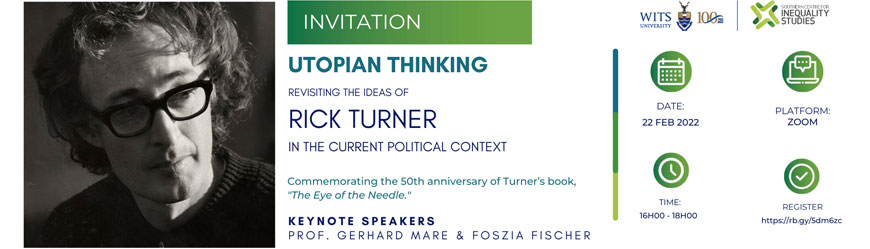

In honour of the 50th anniversary of Turner’s book, The Eye of the Needle, and the relevance of his forward-thinking philosophy to the present day, the Wits Southern Centre for Inequality Studies (SCIS), supported by Maverick Citizen, is hosting an online public lecture on Tuesday, 22 February from 4pm to 6pm: Utopian Thinking, Revisiting the Ideas of Rick Turner in the Current Political Context. To register for the event via Zoom: https://rb.gy/5dm6zc

Philosopher-organiser: Rick Turner and the revival of the trade union movement in the early 1970s

This opinion piece by Professor Emeritus Halton Cheadle from UCT has been published in the Daily Maverick.

Rick Turner’s impact on my life and other students’ lives was profound. He was a philosopher, a political theorist, a teacher, an activist and a friend. He arrived in Durban in 1970. By 1978 when he was brutally assassinated in front of his two young daughters, he had left a legacy that included a scathing criticism of capitalism in his book, The Eye of the Needle, a workers’ college, and the South African Labour Bulletin.

However, his most enduring legacy may be his influence on a committed cadre of student activists who assisted in establishing and organising black workers into trade unions in Durban in the early 1970s.

I will let others speak of his engagement with Steve Biko and the black consciousness movement, of his influence on the National Union of South African Students (Nusas) and of his deep philosophical inquiries into a Marxist epistemology, which still remain unfortunately unpublished. I want to speak on my experience of Turner as a teacher and then on his influence on white student activists organising workers and their role in those organisations. It is important though to first set a context of the late 1960s and early 1970s.

The universities had been racialised by the apartheid state over a sustained period of time — so by the late 1960s, the University of Witwatersrand, which had admitted Nelson Mandela as a law student in the 1940s, was closed to black students. At the University of Natal — there were the two white campuses and a black campus (the medical school) — they were run entirely as if they were separate universities.

Nusas was the predominant student organisation in the English universities at the time. But in 1969, Steve Biko (from UND’s medical school) led the breakaway from Nusas and established the South African Student Organisation. This left Nusas with its predominantly white membership in a quandary as to its role and direction and this opened up a debate that might not have been opened given its smug pride in its multiracialism. It is in this context that a critique of white liberals emerged, and a more radical class-based analysis took place. Turner played a central role in that exploration.

The banning of the ANC and the PAC in 1960 and their move into exile meant their organisational and ideological absence on the campuses at the time — certainly at the University of Natal when I was there. It is no accident that quite simultaneously towards the end of the 1960s and early 1970s there was an independent exploration of the meaning of race and class in various campuses across the country. The exposure to different strands of thinking led to black consciousness on the one hand and brands of non-doctrinaire Marxism on the other. Though sometimes forgotten, it bears reminding that the exile movements were initially hostile to both those ideas and the organisations that those ideas spawned.

There is another part of the context that is important and one that is critical in Rick’s analysis in The Eye of the Needle of the possible sites of struggle.

First, trade unions organising African workers were not illegal and although their leadership was frequently harassed, detained or banned, the organisations themselves were not banned. In other words, despite the authoritarian nature of the state, there was space for organisations to oppose it. There is an important characterisation of the apartheid state in The Eye of the Needle: It was authoritarian and oppressive, but it was not totalitarian. In other words, there was space for internal lawful opposition to occupy — often closed down but only to reopen.

One such space was the one afforded by a liberal university and academic study and research. The political philosopher Michael Nupen and Turner put together political theory courses at bachelor’s and honours’ levels that involved a close engagement with political philosophy that included Hegel, Marx, Lenin, Gramsci, Lukacs, Sartre and Marcuse — even Stalin on the National Question. That space in the universities became occupied by a generation of political scientists (Turner, Dan O’Meara, Sheldon Leader), historians (Charles van Onselen, Phil Bonner, Peter Delius), social scientists (Eddie Webster, Duncan Innes) and economists (Mike Morris, Dave Kaplan, Dudley Horner, Alec Erwin) at liberal universities in the 1970s and 1980s that openly explored class and race theories in their classes and their publications despite the apartheid state’s periodic banning of lecturers, students and books.

As Turner himself stated and Tony Morphet qualified in his introduction to The Eye of the Needle: “In the South African university environment good pedagogics is inevitably radical politics — though the corollary is not always true”.

This allows me to then turn to Turner as a teacher. He was no ordinary university lecturer. His lifestyle was so much on the surface, like that of his students. He lived in a communal arrangement. He let his red rush of hair grow long. He allowed unwashed dishes to accumulate in the sink and the surrounding counters. He had second-hand dilapidated furniture. Sometimes he held seminars in bed when he was sick. He had no palate to speak of — his staple was lentils and his liquor water. Whatever utopia he projected, it certainly wasn’t culinary

His teaching was text-based and Socratic — inspiring us and transforming our thinking by quietly and patiently questioning, probing, rephrasing badly answered questions (sometimes making one sound profounder than one had intended) and posing counterfactuals — all of which you can see and hear at work in The Eye of the Needle. I am not sure that he ever used the term hermeneutics, but that was his method and a method that he employed in his exegesis of the texts.

I remember a public debate between an imam and Turner concerning the differences between Islam and socialism. The imam described the similarities (Moscow and Mecca, Marx and Mohammed, Das Kapital and the Koran etc) and the differences (theism v atheism). Turner (unlike us who were utterly contemptuous of the superficiality of the analysis) quietly responded that these similarities pointed to deeper similarities and, of course, differences. But the differences did not matter because they were matters of belief in the hereafter whereas the similarities dealt with life on Earth. He then engaged in a deeply humanistic exegesis of the text of the Koran to argue for a socialist society in just the hermeneutical way that he used the Christian Bible to do in The Eye of the Needle.

Let me now turn to his influence on the nascent organisation of black workers into trade unions in the early 1970s. There are four interlocking arguments that are central to his theory of change in The Eye of the Needle.

The first argument is that there is space for lawful internal opposition (the survival of the black trade unions established in the 1970s and their and the UDF’s meteoric growth and presence in the 1980s is testimony to that fact). International isolation and the armed struggle were not the only forms of struggle — both of which were critically evaluated in The Eye of the Needle.

The second argument is that a primary site of internal opposition to the apartheid state was the organisation of black workers into trade unions.

The third is that these organisations must be participatory and democratic in character.

The fourth is that the opposition to the apartheid state must by its very nature be black-led — the role of white activists was to support not lead.

That support took different forms — all inspired by Turner and involving Turner despite his banning order, which prevented him, among other restrictions, from lecturing, publishing, attending gatherings and trade union activities. The Institute of Industrial Education was established to serve as a school for trade unionists. The South African Labour Bulletin was published to provide information and stimulate critical analysis and debate on issues that confront workers. Historians were encouraged to recover the hidden history of workers. Economists and social scientists were mobilised to conduct research into poverty datum lines and minimum living wages to support wage negotiations. Advice offices were established to assist workers with individual complaints ranging from underpayments, unemployment insurance, workers’ compensation to the pass laws. But the most critical form of involvement was the direct engagement of white activists in the organisation of black workers into trade unions.

In the space of two years before the first round of bannings of those activists in 1974, trade unions organising black workers were established in the textile, metal, transport and chemical industries.

The constitutions of those unions were constructed to realise Turner’s central arguments regarding participatory decision-making and worker leadership. Workers elected their shop stewards in the workplace. The shop stewards appointed a representative from their number to sit on the branch executive committee of the trade union. The members of the branch appointed a representative to sit on the executive committee of the union, which had the power to appoint and fire officials. It was inevitable that given the demographics of the South African workplace, these executive committees were black — not as a matter of ideology but as one of fact.

Although at the beginning white activists were officials performing important leadership roles, their role was to be scaffolding — to fall away once the trade union was up and running. Although it was our intention to voluntarily move into support roles rather than leadership roles, the state did the job for us. Five of us were banned in 1974 only to be replaced by other white activists.

But by the time that they were banned in 1976, the unions were firmly in the hands of their worker leadership. It should not come as a surprise then that during our banning orders some of us studied law by correspondence so that we could provide a new form of support to these trade unions, namely as labour lawyers.

This is the second 0f a short series of articles reflecting on Rick Turner’s life and writing. The first is here.