Here’s how much kids need to move, play and sleep in their early years

- Catherine Draper

Most of us would agree that we want to encourage children to be physically active, get enough sleep, and keep their screen time at healthy levels.

But did you know that this starts from birth? And, what is enough sleep for young children? Also, given the ubiquity of screens, what is a healthy level of screen time?

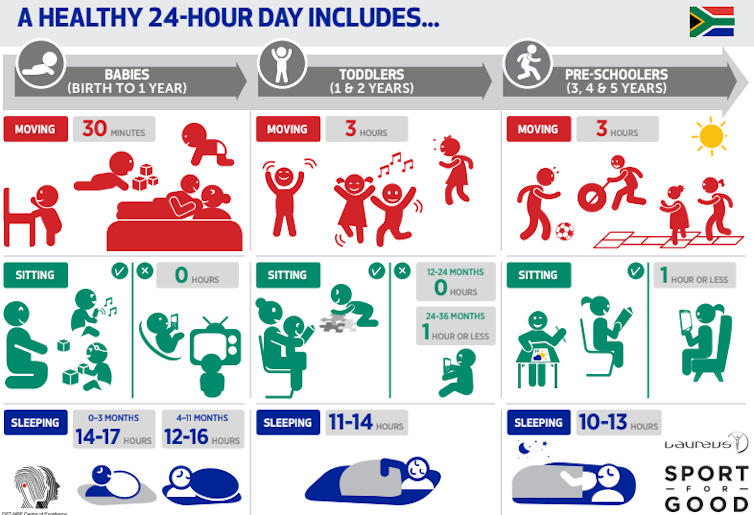

South Africa has just launched 24-hour movement guidelines for children from birth to five years, integrating physical activity, sitting behaviour, screen time and sleep. These guidelines intend to answer these and other questions, providing guidance that can help put young children on the best trajectory for their growth, health and development.

The country is following the example of others that have recently updated or are busy updating their movement behaviour guidelines for the early years – Canada, Australia, and the UK. It’s the first low- and middle-income country to bring out movement behaviour guidelines for this or any age group.

These developments represent a shift towards integrated guidelines for children’s physical activity, sitting and sleep behaviours. These guidelines take into account the natural and instinctual integration of these behaviours across a 24-hour period, and are intended to provide a more cohesive message for parents, caregivers, teachers and practitioners.

Research shows that children from birth to five years who receive support to meet these movement guidelines are likely to grow up healthier, fitter and stronger. They may also have greater motor skill abilities, be more prepared for school, manage their feelings better, and enjoy life more.

The guidelines

The development of the guidelines was supported by the Laureus Sport for Good Foundation South Africa which brought together a panel of stakeholders, practitioners and academics (local and international) from the field of early childhood. The panel considered the best available scientific evidence, the South African context and how the guidelines would be received across the country’s very diverse settings.

The guidelines recommend that children from birth to five years should participate in a range of play-based and structured physical activities that are appropriate for their age and ability, and that are fun and safe. Children should be encouraged to do these activities independently as well as with adults and other children. For caregivers, activities that are loving and involve play and talking with children are best.

These guidelines also emphasise that the quality of what is done when sitting matters. For children younger than two years, screen time is not recommended. Sitting activities that are screen-based should be limited among children aged two to five years. The quality of sleep in children from birth to five years is also important, and screen time should be avoided before bed.

While the educational benefits of screen time receive much attention in the media, there’s little scientific evidence to support the claims of these benefits. And the long-term, potentially negative, impacts of replacing “traditional” games and books with screen-based versions are not yet known.

The World Cancer Research Fund recently highlighted the link between childhood screen time to 12 deadly cancers and short-sightedness. There is also a trend emerging among technologists in Silicon Valley to keep their children away from screens. This should surely be causing us to think twice about the easy role that screens play in little ones’ lives.

Early childhood represents a key window of opportunity to lay down a healthy foundation for children’s movement behaviours, setting them up for a win as far as their growth, health and development are concerned.

The guidelines can help build this foundation and can be used by anyone who has an interest in the health and development of all children from birth to five years – parents and family, educators, caregivers, health professionals, and community workers.![]()

Catherine Draper, Senior Researcher, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.