Mosaic anatomy in an early fossil squamate

- Wits University

A fossil discovered on the Isle of Skye has revealed a new species and family of Jurassic reptile linked to the origins of lizards and snakes.

A study published in Nature by an international team of researchers, led by the American Museum of Natural History and including National Museums Scotland and the University of the Witwatersrand, describes a previously unknown Jurassic reptile that lived around 167 million years ago. The species has been given the Gaelic name Breugnathair elgolensis meaning ‘false snake of Elgol’, referencing the area on Scotland’s Isle of Skye, where it was discovered.

Breugnathair had snake-like jaws and highly recurved teeth, similar to those of modern-day pythons. Unlike living snakes, it had the proportions and limbs of a lizard. The fossil is among the oldest and most complete Jurassic lizards known to science.

Breugnathair was a squamate, the largest order of scaled reptiles, including lizards and snakes. The species has been placed in a new family Parviraptoridae, an enigmatic group of extinct, predatory squamates. Previously known from very incomplete remains, parviraptorids were thought by some to be the first snakes. Breugnathair might therefore provide evidence of the lizard-like ancestors of snakes, but it also has primitive anatomical traits suggesting that parviraptorids were stem-squamates, the predecessors of all lizards and snakes.

Lead author Dr Roger Benson, Curator of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History, said: “Snakes are remarkable animals that evolved long, limbless bodies from lizard-like ancestors. Breugnathair has snake-like features of the teeth and jaws, but in other ways is surprisingly primitive. This might be telling us that snake ancestors were very different to what we expected, or it could instead be evidence for evolution of predatory habits in a primitive, extinct group”.

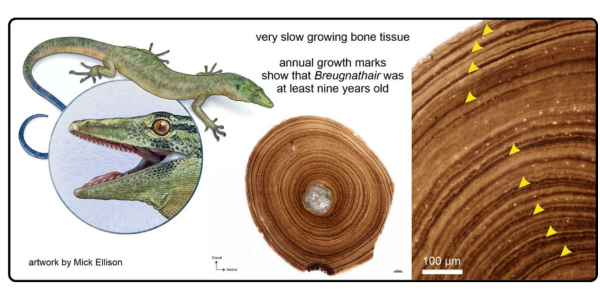

“The internal microstructure of the bones of this animal indicate that it grew slowly and was at least nine years old. The slow growth rate is similar to that seen in living varanid lizards,” says co-author Dr Jennifer Botha from the University of the Witwatersrand.

Dr Stig Walsh, Senior Curator of Vertebrate Palaeobiology at National Museums Scotland and co-author of the study, said: “The Isle of Skye is one of the most important Middle Jurassic sites in the world. Breugnathair elgolensis is a remarkable addition to the fossil record, helping to rewrite our understanding of the evolution of snakes and lizards. We’re delighted to add it to the other amazing finds in the National Collection that were discovered in Skye, truly Scotland’s Jurassic Isle”.