Ethical leadership for a just society

- Wits University

Wits Chancellor, Dr Judy Dlamini called for ethical leadership to tackle inequality in South Africa.

Dlamini delivered the 2021 Sefularo-Sheiham Memorial Lecture via Zoom on 20 April 2021.

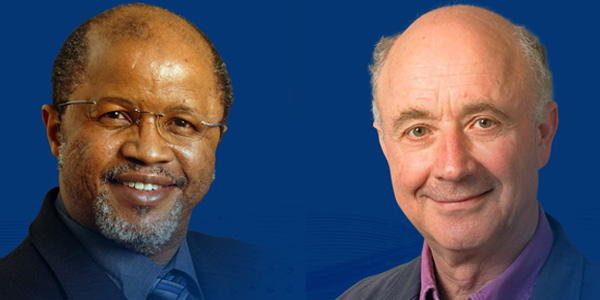

The lecture commemorates medical giants and health activists, Dr Molefi Sefularo and Professor Aubrey Sheiham, both Wits alumni. Dlamini described them as “two Witsies who were united in the advocacy for social justice especially in public health.”

In her address, titled, Covid-19 and the social determinants of health inequalities: Reflections on ethical leadership for health equity and a socially just recovery, Dlamini highlighted the inequalities that Covid-19 exposed and which affect access to health.

“Equity in all aspects of our lives remains elusive and health is no different. The Covid-19 pandemic was a rude reminder of this fact and exacerbated that divide that already existed,” she said.

“Covid-19 has exposed the impact of the intersectionality of race, social class, gender, ageism, disability and geography in health access and health outcomes.”

Dlamini, a medical doctor by training, said that within the healthcare sector, the main causes of inequality are income, housing and sanitation, access to quality education, employment conditions of work, and diet. These inequities show the intersectionality of poverty and inequality.

Gendered inequality and Covid-19

Dlamini said that inequality is also gendered, and highlighted the vast income inequality between women and men. This disparity means that women suffer the most during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Although SA’s new democratic dispensation in the 1990s enabled a decline in poverty, “females are more likely to remain poor than males due to existing inequalities,” said Dlamini. In employment, Black women are the most disadvantaged, with opportunities unequal compared to their male counterparts. Additionally, due to females living further below the poverty line than males, they become more vulnerable, added the philanthropist.

“The Global Health 50/50 report shows showed that more than 70% of CEOs in global organisations active in health are men and just 5% are women. Not only are female health workers less likely to be in management positions, they are on average paid less than male counterpart, for doing the same job.”

The lockdown instituted by government in a quest to curb the spread of Covid-19 had severe impacts on the poor, with more job losses for people in low-ranking jobs. These employees were unable to work from home due to their domestic environment.

Dlamini noted that, with the 3 million jobs lost during Covid-19 as reported by National Income Dynamics Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey, women – mostly Black women – accounted for two- thirds of these job losses.

She added that women in rural areas were hardest hit by Covid-19 – they suffered great income loss and relied on borrowing money from loan sharks to sustain their households and productions. When it came to tech/online innovations and the “new normal” brought about by Covid-19, rural communities were alienated. Online learning was a challenge due to limited access to resources such as laptops, and lack of electricity.

In light of the inequalities exposed by Covid-19, Dlamini asked: “What opportunity, therefore, does the pandemic bring? What will it take to achieve equity and be ready for the next pandemic?”

The call for ethical leadership

A leading businesswoman who wants to contribute positively to humanity, Dlamini believes that ethical leadership and collaboration amongst leaders is required to tackle inequality in South Africa.

She said the main challenges in the country which call for ethical leadership are unemployment, poverty, gender based violence, and inequality.

“The multi-faceted nature of inequality requires us, especially leaders in all sectors, to address the underlying systemic intersecting causes of inequalities. Principles of social justice and equity should govern the frameworks of intervention if we are to emerge as better societies. We need ethical leadership to drive the change that our country needs,” she said.

Dlamini noted that the lack of ethical leadership was one of the underlying causes of many failures in society. She implored everyone to make efforts to lead ethically.

“I believe that if each one of us in this lecture, in the country, across sectors, deliberately and consistently try to lead ourselves and others ethically, we would edge closer to a just and equal society. Even better if we collaborate our efforts; it would have a multiplier effect and be a catalyst for the desired change, including social cohesion.”

Dlamini said the Covid-19 Solidarity Fund was a perfect example of collaboration to effect positive change.

She called on all leaders in various spheres of society to unite in tackling the existing inequalities in the country, which also play a role in access to quality healthcare. “The pandemic has underscored the importance of universal healthcare coverage and therefore the importance of tackling inequality,” she said.

Dr Molefi Sefularo: Universal health activist

Speakers at the lecture hailed Sefularo, who was the Deputy Minister of Health at the time of his premature death in April 2010, for his health activism. He was described as an advocate for social justice and the implementation of health equity. He advocated policy reform that would address the inequities of the past. Sefularo completed his medical degree at the Medical University of South Africa. He obtained his public health management diplomas from Wits.

Dr Gwen Ramakgopa, Chancellor of Tshwane University of Technology, said Sefularo pursued his conviction of health for all. “As a parliamentarian he used his position as MEC and later Deputy Minister for Health to advance access to health and towards strengthening the public health system.”

Sefularo’s daughter, Masechaba Sefularo, said her father was a great giver and held many titles – politician, activist, medical doctor, and mentor.

“My father learned the lesson of service, selflessness, sacrifice and justice,” she said.

“It’s these values and ideals that formed his passion, merging his knowledge from his upbringing, his experiences, his education and influence to advocate for equal access to quality healthcare.”

During his time as Deputy Minister of Health, Sefularo outlined a programme of action based on 10 key priorities, which he identified as solutions to challenges facing the healthcare sector. Amongst his priorities was the provision of strategic leadership and the creation of a social compact for better health outcomes; implementation of the National Health Insurance; and improving of the quality of health services.

Dr Aubrey Sheiham: Global pioneer in public health

Professor Aubrey Sheiham was born in 1936 in Graaff-Reinet in the Western Cape. He completed his Bachelor of Dentistry degree at Wits in 1957. He left South Africa for the UK during apartheid, initially working in general dental practice and then at the Eastman Dental Hospital. Sheiham was a global pioneer in public health and a highly respected scholar. He was an inspirational teacher, mentor, health equity researcher and public health advocate for social justice and global health.

Professor Sir Michael Marmot, Director of the Institute for Health Equity at University College London (UCL) spoke highly of Sheiham’s character, stating that he was a “scrupulously honest” individual, fearless, and had high moral standards. He added that as Sheiham’s “career developed, he got increasingly committed to the issue of equity.”

Professor Robert Watt, Chair and Honorary Consultant in Dental Public Health at UCL also paid tribute to Sheiham. He said Sheiham had a major influence on research policy and training across the world.

“He raised the political policy profile of health and championed the need for radical transformation and reform of health services and health policy,” said Watt, adding that Sheiham was also a global scholar with an impressive publication record.

“Across his career he published 480 papers, including publications in The Lancet British medical journal. He was a leading figure in global health policy.”