Engineering empathy

- Deborah Minors

In search of ways to help his father recover from injuries suffered in a motorbike accident, Nabeel Vandayar enrolled at Wits to study medicine.

He soon switched to biomedical engineering after realising that this field holds promising solutions to his father’s speech and mobility challenges.

The field of biomedical engineering would be poorer if Nabeel Vandayar, 26, had pursued his boyhood passion for cricket rather than medicine.

The promising Gauteng Schools batsman matriculated from Jeppe Boys High – where he “took far too many extra subjects!” – and enrolled at Wits in 2013 for the MBBCh degree.

“The reason I chose medicine was personal,” says Vandayar – his father had been left partially disabled after a motorbike accident in 2011.

More than medicine

“By the end of my first year of medicine, my father had made a significant recovery after months of rehabilitation, but I realised then that medicine can only do so much,” says Vandayar. “There’s certain things that medicine cannot do. My Dad still couldn’t ride his bike, for example, and medicine couldn’t give him the quality of life he enjoyed before the accident.”

Vandayar finished first-year medicine and then switched to the School of Electrical and Information Engineering to study biomedical engineering.

“Biomed is probably the most challenging undergraduate degree at Wits because the courses you study are so different. You could start off the day with physiology and anatomy with the medical students, by lunch time you have created software to interface with an electric circuit, and that afternoon you have done complex mathematics in signals and systems.” says Vandayar.

“The interesting thing is that these different courses build skills which, when combined, contribute to a biomedical solution in the real world. Biomed is not just about solving a problem, it’s about changing lives.”

3 idiots and an epiphany

In his final year of biomedical engineering, Vandayar was awarded a bursary by Health Tech, a subsidiary of IT service management company, Altron. While doing vacation work as a data analyst, he was exposed to machine learning for the first time and its potential to be applied to an individual.

Machine learning is the study of computer algorithms that improve automatically through experience, and by the use of data. It is seen as a part of artificial intelligence (AI).

Vandayar came up with a predictive model to establish if a patient will become diabetic, based on the patient’s medical aid claims history.

There’s an Indian movie called 3 Idiots, Vandayar says, which is a satirical film about “a mechanical engineer, like my brother, who designs a vacuum device to help a mother deliver her baby during a difficult birth – kind of like MacGyver”.

That movie, along with the many TEDx Talks on AI that Vandayar watched at the time, showed him the potential for AI to solve medical problems.

Inspired AI

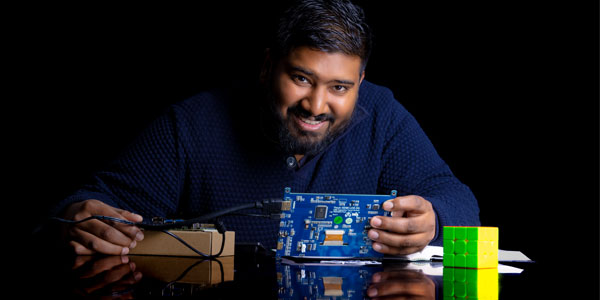

Vandayar’s fourth year information engineering research project was a low-cost hand gesture recognition system. Its design and use enables people with certain movement disabilities – such as the inability to type due to decreased finger dexterity – to use a computer by performing other gestures that they can do comfortably.

“Disability has different ranges,” says Vandayar. “For example, my Dad can’t type on a computer as well as he used to. So I created a customisable system that enables people with specific disabilities to perform movements that they are able to perform.”

Vandayar presented this research at the SAUPEC/RobMech/PRASA conference (Southern African Universities Power and Engineering/Robotics and Mechatronics/Pattern Recognition Association of SA), with co-author and fellow Witsie, Timothy McBride. Their research was published in 2019.

Vandayar’s early research success galvanised his promotion to data scientist at Health Tech. In 2021, he presented his master’s research proposal to his supervisor, Associate Professor Ken Nixon in the School of Electrical and Information Engineering.

“My motivation for all this comes back to my Dad. He had suffered head injuries during his accident, which resulted in a tendency to stutter in stressful situations – for example, when meeting new people or speaking on the phone. This inability to speak fluently is very inhibiting compared to how he used to speak.”

Recognising Vandayar’s motivation “to solve problems using engineering and empathy”, Nixon recommended a joint supervision with Dr Victor de Andrade, Senior Lecturer in the Audiology Division, Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology, in the School of Human and Community Development at Wits.

Superman and a stutter

“Autonomy and self-sufficiency is something people take for granted until they lose it,” says Vandayar, and references the actor Christopher Reeve who played Superman in the film adaptation of the comic book superhero. In 1995, Reeve was thrown from a horse and broke his neck. The injury paralysed him from the shoulders down. Superman, ironically, was confined to a wheelchair and used a mechanical ventilator for the rest of his life.

“My Dad is my superhero,” says Vandayar. “He dropped out of varsity to become a taxi driver, he opened bottle stores, he was a successful businessman. After the accident, he was doing stuff on the computer, and he always asked me for help, or got me to speak for him on a call because of his stutter. Even though I was always happy to help, the best way to help was to give him a way to do these things on his own.”

Vandayar’s master’s research focuses on providing a ‘speech filter’ for stuttered speech that delivers a fluent voice to a listener.

The idea is to apply machine learning algorithms to an audio recording of a person’s voice to detect if a stutter is occurring. If it is, the next word is predicted based on the context of the sentence up until that point, and passed to a programme called Tacotron (developed by Google). Tacotron generates audio of what the person is trying to say. The corrected audio is then transmitted to the listener and sounds more coherent because it does not include the stutter.

“Tacotron not only takes written text and converts it to speech but makes speech sound like the original person. You give Tacotron a sample of what you sound like and it can then generate sentences you give it using your voice,” says Vandayar. “The amazing Stephen Hawking could possibly have given lectures in his original voice if Tacotron had been connected to his computer."

Vandayar acknowledges that it would be ambitious for his master’s research to actually solve a stutter. “My research is about taking the building blocks that exist, putting them together in a new way, and hopefully coming up with a solution that reduces the anxiety that a stutterer experiences, by recreating their speech in a way that makes it easier for others to understand them.”

His aim is to enable some humanity, autonomy and less anxiety for the stutterer by making the listener understand the person who is stuttering. “Instead of giving the person who stutters an additional technology crutch to adapt to, such as delayed auditory feedback, why not get the technology to do the heavy lifting so that the person can just speak freely and be understood?“

Open source solutions

Vandayar now works as a data engineer at a financial services tech company, where he is establishing a healthcare division.

He’s also co-founded an open source research group, comprising of doctors, nurses, biomed engineers and non-technical stakeholders in the African healthcare space, to encourage research collaboration and innovation.

“People don’t work on these technologies unless they have a vested interest – as I do – and I think this needs to change. Right now what I’m most passionate about is improving public health using AI,” he says.

Indeed, engineering with empathy.

- Deborah Minors is Senior Communications Officer for Wits University.

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the 12th issue, themed: #Solutions. We explore #WitsForGood solutions to the structural, political and socioeconomic challenges that persist in South Africa, and we are encouraged by astounding ‘moonshot moments’ where Witsies are advancing science, health, engineering, technology and innovation.