"Little Foot" skull reveals how this human ancestor lived

- Wits University

Micro-CT scanning of “Little Foot” skull reveals new aspects of the life of this more than 3-million year-old-human ancestor.

“The morphology of the first cervical vertebra, or atlas, reflects multiple aspects of an organism’s life,” says Beaudet, the lead author of the study. “In particular, the nearly complete atlas of ‘Little Foot’ has the potential to provide new insights into the evolution of head mobility and the arterial supply to the brain in the human lineage.”

The shape of the atlas determines the range of head motions while the size of the arteries passing through the vertebrae to the skull is useful for estimating blood flow supplying the brain.

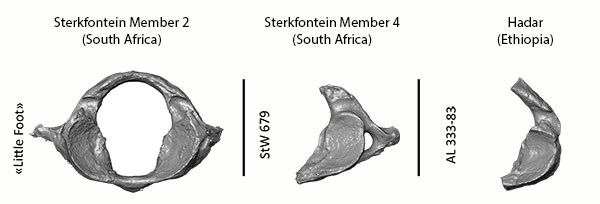

“Our study shows that Australopithecus was capable of head movements that differ from us. This could be explained by the greater ability of Australopithecus to climb and move in the trees. However, a southern African Australopithecus specimen younger than ‘Little Foot’ (probably younger by about 1 million years) may have partially lost this capacity and spent more time on the ground, like us today.”

The overall dimensions and shape of the atlas of “Little Foot” are similar to living chimpanzees. More specifically, the ligament insertions (that could be inferred from the presence and configuration of bony tubercles) and the morphology of the facet joints linking the head and the neck all suggest that “Little Foot” was moving regularly in trees.

Because “Little Foot” is so well-preserved, blood flow supply to the brain could also be estimated for the first time, using evidence from the skull and vertebrae. These estimations demonstrate that blood flow, and thus the utilisation of glucose by the brain, was about three times lower than in living humans, and closer to the those of living chimpanzees.

“The low investment of energy into the brain of Australopithecus could be tentatively explained by a relatively small brain of the specimen (around 408 cubic centimetres), a low quality diet (low proportion of animal products) or high costs of other aspects of the biology of Australopithecus (such as upright walking). In any case, this might suggest that the human brain’s vascular system emerged much later in our history.”