The bones know best – Human identification and variation at Wits

- Deborah Minors

Forensic anthropology is the analysis of human remains. A new unit at Wits studies the ancient and modern deceased as a service to society and to science.

The Human Variation and Identification Research Unit (HVIRU) in the School of Anatomical Sciences at Wits launched on Monday, 28 November 2016. This research unit has five focus areas:

- Forensic anthropology

- Craniofacial identification

- Bioarchaeology

- Human variation

- Taphonomy

“The research part of forensic anthropology deals with the analysis and identification of human remains, mostly for medical legal purposes. Although it focuses on the dead, it may also focus on the living – as in craniofacial identification – but this is basically research relating to identification from skeletal remains.

Maryna Steyn, Head of the School of Anatomical Sciences, says that the unit is research and service orientated.

.jpg)

Prof. Maryna Steyn, Head of the School of Anatomical Sciences at Wits

“The research part of forensic anthropology deals with the analysis and identification of human remains, mostly for medical legal purposes. Although it focuses on the dead, it may also focus on the living – as in craniofacial identification – but this is basically research relating to identification from skeletal remains,” says Steyn.

In addition to research, the unit is service-orientated and collaborates with the Victim Identification Centre and Forensic Pathology Services. In this regard the unit deals with identification of unknown decomposed or skeletonized bodies, analysis of trauma and disease, and estimation of age.

“From our case analysis a number of questions arise, which we can then address through research. It is a dynamic process of practice informing research, and vice versa. Thus far we’ve done 24 cases,” says Steyn.

Putting a face to the bones

Regarding craniofacial identification, the unit collaborates with the South African Police and other universities. Craniofacial identification deals with identification from the skull and face of both the living and the dead. Steyn says South Africa has a massive problem with unidentified dead – “many bodies remain unidentified”.

The unit conducts research on craniofacial approximation and craniofacial superimposition. For the living, craniofacial identification includes photo-to-photo comparison or identification of perpetrators from CCTV images. Current research projects include a study of identification bias, which results when individuals show differential abilities, stemming from personal demographics, to correctly identify people from reconstructions.

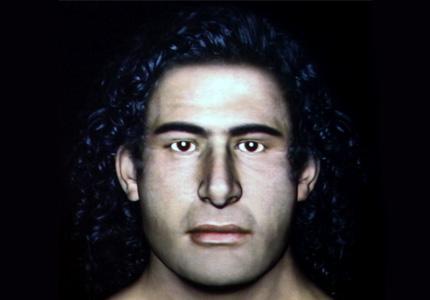

Lynne Schepartz, Head of the Biological Anthropology division in the School introduced the “Griffin Warrior”. Together with Dr Tobias Houlton, a postdoctoral biological anthropologist and craniofacial expert, Schepartz reconstructed the face of the 3000-year-old 30-35-year-old male whose body was unearthed in Greece.

“The nose is one of the most important areas in facial reconstruction. This was missing in the Griffin Warrior, but the other key areas were preserved,” says Schepartz.

The warrior’s nose was reconstructed using data for an average, modern Greek male nose, and similarly modern comparative data were used to add skin colour and texture. The hair was reconstructed from the ancient wall paintings and art work.

The reimagined face of the Griffin Warrior

Human remains in an archaeological context

Bioarchaeology integrates the theory and methods of biological anthropology with those of archaeology (as well as social anthropology) to study human skeletal remains from archaeological contexts. Researchers explore the life experiences, social roles, health, modes of burial, etc., of ancient and historic peoples. The unit focuses on palaeopathology and diseases in the past and researches how those diseases impact modern populations.

“We have a strong focus in Bioarchaeology. We have done work on, amongst others, a mummy from Botswana, on tuberculosis and skeletal remains, nutritional shortcomings represented in bones in China and Greece, and work on historic mining populations,” says Steyn.

The guest speaker at the launch, Prof. Ron Pinhasi, University College, Dublin, spoke on the topic: Using aDNA to understand human evolutionary interactions and dispersals in relation to major social/technological transformations.

Pinhasi is a Professor of Archaeology with an interest in human evolution over the past 15 000 years. He uses aDNA (ancient DNA) and Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) to research the ‘paleogenetics’ of prehistoric populations.

“aDNA can time-stamp genetic diversity instead of us having to infer past patterns from modern data,” he says. He presented his work on extracting aDNA from the petrous bone (in the inner ear). “This is the densest human bone with the highest success rates (over 50%) when it comes to extraction of aDNA”.

Pinhasi discussed the Ancient DNA and Human History study, which revealed a “human paleogenomic revolution”. This research encompasses the most specimens ever incorporated in a study – 10 000, mostly from northern Europe, and demonstrates that the actual movement of people - rather than just ideas and technology - led to the first spread of farming across Europe. Pinhasi highlighted the lack of information on ancient nuclear DNA in Africa, which he hopes to address through collaborating with the HVIRU.

The knowledge and appreciation for modern biological human variation has always been a core component of biological anthropology and Wits has a long history of research in this area. The establishment of HVIRU is the latest page is this rich history.

Steyn says, “I think in our country specifically it has a more relevant reason – it helps us understand human variation, which plays a role in the process of transformation.”