The 46-year-long Wits LLB that never was

- Bruce Murray

Nelson Mandela is among Wits University’s most famous alumni, but he is not a graduate of the University.

Mandela was a law student at Wits University from 1943 to 1949 but failed the final examination on three occasions between 1947 and 1949. On the third occasion, he applied to the Dean of Law, Professor HR Hahlo, for permission to write supplementary examinations in the three papers he failed. The Board of the Faculty of Law denied permission, as the regulations allowed for a maximum of two supplementary examinations.

“Women and Africans not disciplined enough to master law”

Evidently, the advice Hahlo subsequently gave Mandela was to abandon the LLB, which was required to become an advocate – a career Hahlo deemed unsuited to Africans (as it necessitated being part and parcel of the mores of the people – meaning whites – if the advocate were to get any business) and instead to qualify directly as an attorney. Mandela took the advice and passed the Attorney’s Admission examination at the end of 1951.

There is a strong tradition that places the blame firmly on Hahlo for Mandela’s failure to qualify for a Wits LLB. Hahlo was a racist who gave Mandela, the first African law student at Wits, the gratuitous advice that Africans and women were unsuited to the study of law. “His view,” Mandela recounted in his autobiography, “was that law was a social science and that women and Africans were not disciplined enough to master its intricacies.”

Certainly, Hahlo was unhelpful – Mandela reckoned “he could have been more friendly and helpful to me” – but he was not unfair. Mandela ultimately passed all the courses for the LLB he took from Hahlo, six out of 14, except Jurisprudence in 1947. The examiners who consistently failed Mandela were the noted liberal advocate Rex Welsh, in Jurisprudence 1948-9, and the Scot, advocate RG McKerron, in the Law of Delicts 1947-9.

Frequent failure, rising revolutionary

Mandela had always struggled with examinations at Wits, but his performance in his final-year LLB examinations is puzzling. By 1947, he had completed his articles with the law firm Sidelsky and Eidelman, and with the aid of a substantial loan from the Bantu Welfare Trust (which he never repaid), he was able to move from part-time to full-time study. Yet, in 1947, he failed all six papers badly, followed by four failures the next year, and three in 1949.

A likely explanation is that Mandela’s activities in the newly formed ANC Youth League consumed him. In 1947, he became secretary, responsible for political organisation. By 1948, according to his wife, Evelyn, Mandela was often away from home days at a time, engaged in Youth League activities.

After qualifying as an attorney, Mandela decided on another attempt at the LLB. He enrolled again at Wits for the 1952 academic year. He never really made a go of it though, becoming deeply involved as volunteer-in-chief in helping organise the Defiance Campaign. Wits cancelled his registration on 18 July for the non-payment of fees. In August, Mandela opened his own law practice, soon to be joined by Oliver Tambo.

Prisoner of conscientiousness

Mandela still hankered after an LLB and at the end of the 1950s enrolled as an external student with London University. That was in the midst of the Treason Trial (1956-61), with Mandela one of the accused. In 1964, he wrote and passed his first London LLB examinations while awaiting sentence in the Rivonia Trial, which many expected would be the death penalty.

Sentenced to life imprisonment on Robben Island, he was permitted to continue with his LLB studies – the only prisoner allowed to study law. In 1967, he successfully completed Part 1 of the London University LLB examination, but at that point, he again stalled, and his task became impossible when, in 1970, the apartheid government put an end to his overseas supply of books through the British ambassador.

Out of a sense that he was getting nowhere with his London University LLB, Mandela wrote in October 1974 to the Dean of the Faculty of Law at Wits inquiring whether it would be possible for him to write Wits’ final LLB examination in November 1975. The response he received from the Registrar’s office was cautious and legalistic rather than sympathetic, and the status of his credits questioned. Nonetheless, an application form was sent to him – but he never received it. The Department of Prisons blocked his correspondence with Wits and refused him permission to continue his LLB studies, whether through London, Wits, or UNISA.

Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela, LLB (UNISA, 1989)

Ultimately, in 1981, it was the Dean of Law at UNISA, Professor Willem Joubert, who persuaded the government that it was ridiculous to continue blocking Mandela’s LLB. He enrolled for the UNISA LLB, and finally qualified in 1989, 46 years after his first registration for the degree at Wits. It was a remarkable feat of persistence, particularly as, since his imprisonment, there was no prospect Mandela would ever practice law again.

Mandela’s experiences at Wits were certainly not without their influence on his personal and political development. In the first instance, Wits provided him with the legal education he required to launch his career as an attorney – his ambition since arriving in Johannesburg from the Transkei.

Second, Wits represented Mandela’s first exposure to whites, and white prejudices, on any considerable scale. Wits had only recently begun opening its doors to black students, and Mandela was treated as something of an alien, rather than embraced, giving something of a personal edge to his participation in the emerging struggle against “the oppression of our black people”.

Apart from white prejudice, Wits also exposed Mandela to a “new world”, a “world of ideas and political debates, a world where people were passionate about politics”. Wits opened up Mandela to political dialogue, and also friendships with persons of other races, many of them communists, which ultimately tempered his assertive anti-communist African nationalism, and his opposition to political alliances with other race groups.

In the later view of certain “Africanists”, it was Mandela’s time at Wits that contributed to “a watering down of his affiliation to radical African nationalism [Africanism] and of becoming more amenable to the influence of communists”. As he conceded in his autobiography, his friendships with people like Ismail Meer and Ruth First, and his observation of their own sacrifices, made it “more and more difficult to justify my prejudice against the party”.

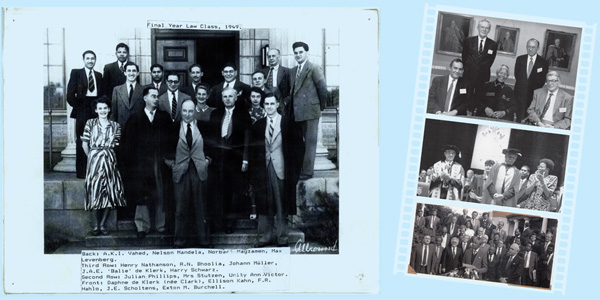

Mandela never bore an enduring grudge against Wits, which he came to perceive as an important instrument of transformation. In 1982, while in Pollsmoor Prison, he ran for the post of Chancellor of Wits, and in 1991, after his release, he accepted an honorary doctorate in laws from the University. In the spirit of reconciliation, he requested a reunion of the law class of 1946, including those who had snubbed him as a student. The reunion took place in November 1996.

“Wits made me what I am today,” Mandela said at the reunion. “I am what I am both as a result of people who respected me and helped me, and those who did not respect me and treated me badly.”

- Bruce Murray is Emeritus Professor of History at Wits and author of Nelson Mandela and Wits University, a paper published in the Journal of African History in 2016. Murray is the author of the books Wits the Early Years: A History of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg and its precursors 1896-1939 (Wits Press, 1982) and of Wits the Open Years: A History of the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg 1939-1959 (Wits Press, 1997).

- This article first appeared in Curiosity, a research magazine produced by Wits Communications and the Research Office.

- Read more in the fifth issue, themed: #Mandela100 where Wits students, academics, researchers, activists and leaders reflect on Nelson Mandela’s legacy and explore his impact over a lifetime.